Approaches to Inner Life, Part Five

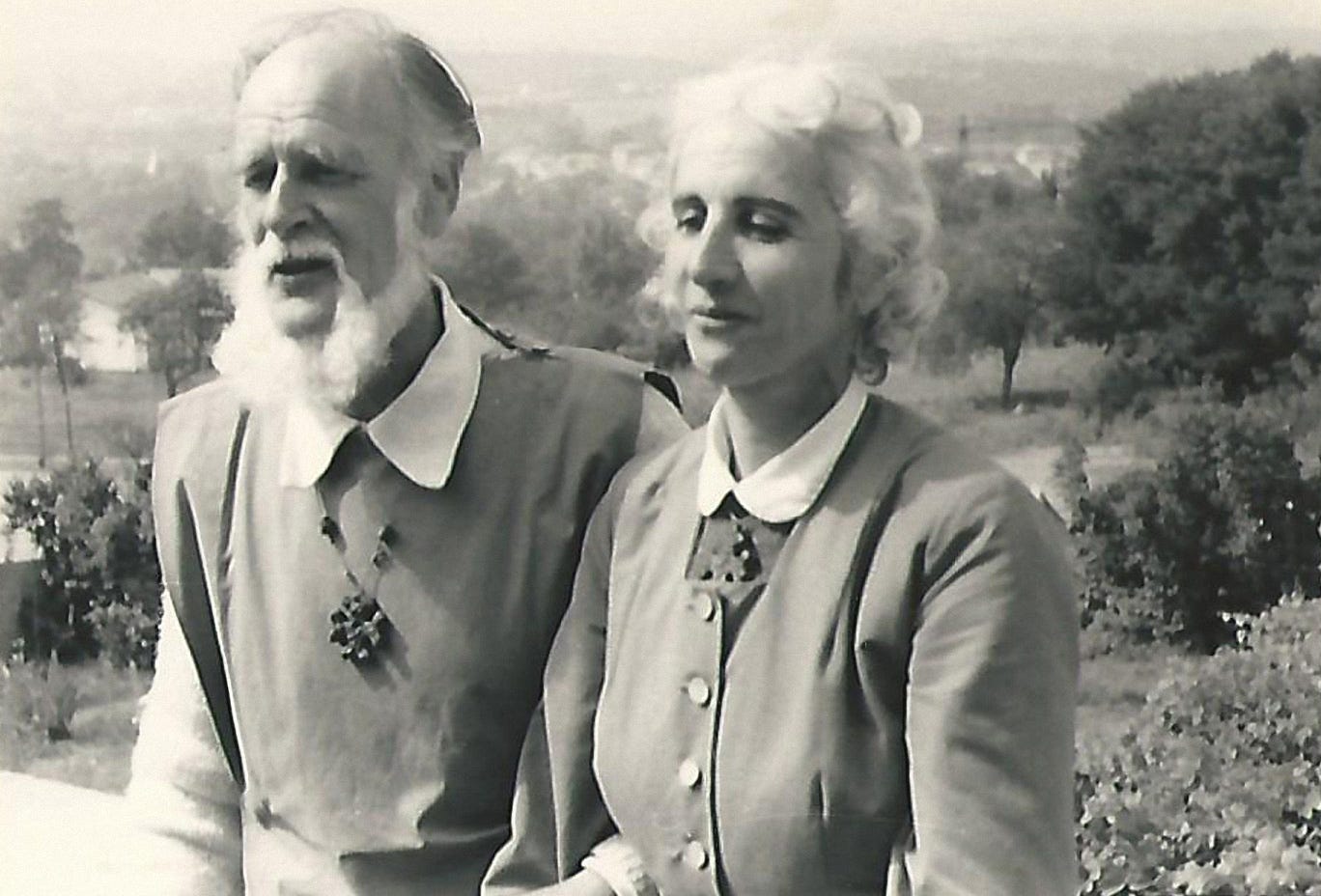

Lanza del Vasto

Translated from

LANZA DEL VASTO, APPROCHES DE LA VIE INTÉRIEURE

ÉDITIONS DENOËL, 1962

On Character and Person

The catechism teaches us that humans are creatures made of soul and body. However, in body and soul, they present themselves to us as a person.

A body — you think you know what that is, or at least believe you do. I think you don’t really know, and it would be presumptuous of me to claim that I do, since knowing what the body is would mean possessing all of nature’s secrets. I’m not one of those who despise the body. I maintain that the body is our probe, our measure, our key to all creation, for the body is the only thing in the world through which we sense things both externally and internally at once. It is consequently the path by which we can penetrate to the interior of everything; but it’s not my subject to discuss the body this time. I won’t speak to you either about the soul, its nature, unity, or immortality. Today I want to talk to you about the person; or better put: about character. For the word “person” has two distinct meanings. Person means: a role played in theater, and person also means: the flourishing of spiritual substance. It’s in this second sense that theologians say God is made of Three Persons. But when it comes to human persons, it's almost always the term “character” that would be more fitting.

Therefore, every human has not only a body and a soul, they possess — or better said, they have (since “possess” is too strong a word) — they have a character. But I will say that the catechism is right to pass over this important part of human nature, for character is not a creature of God. The body, as a natural being, is a creature of God, and the soul, as a spiritual being, is a creature of God; but the character that exists between the two is a creation of humans, a social fiction. It is a composite and not an element, a passage and not a being.

The first thing to note when studying character is its unreality. Character is a fabricated, imaginary being, more or less empty and false. It isn’t born with the person but is gradually formed through education. Its fabrication continues at school, in the army, during study, at the factory, or in the salon, through all the friction and experiences of social life: instruction, culture, laws and customs contribute to it — all of which are artificial. Language is one such artifice, and one of the main ones, and the very existence of character is not only confirmed but almost created by the name others give it, the reputation they make for it, and by the “I-self” that it grants itself.

The great driving force of character, what produces it, is vanity. Vanity is emptiness (vain means empty). Yes, at the center of character, emptiness forms what we might call an air pocket, an “a-spiration,” and in this void the substances from both poles come together. It is vanity that inflates the character and pushes it forward in life, that stirs it and makes it take up as much space as possible, until the vanities of surrounding characters push back and put it in its place.

If Persona means a role played by an actor on stage, it’s natural that character should be first and foremost a mask, a theatrical costume and, ultimately, a puppet. We might ask ourselves what is the reason for being of this strange entity that doesn’t exist, and what we’re going to do with it.

Though empty and unreal, it is nevertheless indispensable. Character, in fact, has two or rather three reasons for being: action upon others, self-expression, and protection of nature. What can we, what should we do with it? We shouldn’t think it’s easy to know how to use it and that, empty and non-existent as it is, it won’t resist our efforts to employ it. Nothing is easier, in all human affairs, than to take the means to ends and to stop halfway; and this is precisely what people who mistake themselves for their character do. Let’s not fool ourselves — this applies to the vast majority of cultured people who don’t simply take themselves for their bodies. In this authorless comedy where character is engaged, humans are duped. They act without even knowing they’re acting, they act while believing they’re authentic, and this dummy inflated with emptiness, imaginary and rigged, absorbs all the forces of being.

One could say that education, morality, and culture aim to produce persons. Years of training under strict masters, schools, libraries, theaters, games, encounters, travels, knowledge, know-how, manners, social grace, gifts, means, charms, opportunities and all the civilization this implies are necessary, but not always sufficient, conditions for forming a person.

Nothing, in the world’s eyes, is more estimable, lovable, enviable than an accomplished person. Success, honor, happiness, fortune and glory seem their due. What is the reason for this prestige in the eyes of common people? Here’s the reason: it’s that their spiritual nature is perfectly clothed.

And we must understand that the soul, no more than the body, cannot present itself naked in society.

First, for the good reason that the soul is invisible: it can only appear in the clothing of personhood. The body dresses to hide itself, the soul dresses to appear. Moreover, both forms of dress meet, for bodily clothing, insofar as it represents and signifies, is one of the manifestations that constitute the person.

But why dress up? Why this decorative lie? This representation, what does it represent? If wearing clothes is universal among humans, it must have some profound and, no doubt, religious reason.

It is too easy to denounce the fact that, beneath the plumage and cloak that such a character parades around in, there hides a creature rather like an earthworm; to reduce it to the appearance of a worm would be to give it an even falser form than the artifices that decorate it. For humans are less than what they pretend to be and more than what they appear. That’s why they cover themselves with signs of their pretension and thereby hide the reality of their appearance: their nakedness. As soon as they adorn and deck themselves out, humans place themselves at some degree of a social and spiritual hierarchy. They are no longer simply what they are; they represent what they want to be, may be, must be. And it’s not vanity that’s at issue originally, but rather the immense aspiration toward the totality of being. And the person is not: they represent. They do not lie: they represent; they represent the truth about human nature which is double, for humans are both possibility and passage.

In representing, humans give themselves meaning. They don’t show their form, but rather the meaning of their transformation. Representation is not merely expressive activity; it’s effective magic, it’s a religious obligation, it’s a spiritual exercise — it’s the first of all duties.

For there is neither meaning nor transformation for humans if the Goal is not fixed and if this Goal has no being or form, if this goal, this being, this form are not constantly present.

This goal, this being, this form is Divinity.

To make it present is to present oneself to it through offering and prayer, and to represent it — that is to recall and reproduce its form. Finally, it’s to conform to it by imitating oneself, incorporating it, clothing oneself in its form.

The Festival is the periodic return of Representation. Ceremony is representation properly religious, that is to say, obligatory. It is accompanied by other representations more free, more intimate, more exalting: sacred dances and theater where the actor takes on the figure and mask of the god, lets himself be invaded by the breath, intoxicated by the force of the god and by His voice, and for a moment become Him.

But there are people who play this role permanently: such are the Priest and the King (originally these were one).

In the midst and at the summit of the people, they represent divinity and their whole life is festival, rite and ceremony, that is to say not wealth and pleasure, but Representation.

Now, the lord represents the King in his fief, the captain in his army, the master in his school, the boss in his workshop, the father in his family; and even the lowest of free men, insofar as he is master of his body and lord of his life, holds a particle of royal majesty and a reflection of divine light. And this particle of majesty and this reflection of the divine is the Person.

Here is a new aspect of the Person, which we had first presented as eminently futile and false, and here are new indications about how to behave toward personhood. For the person can be divine or diabolical or vain. It becomes diabolical as soon as one believes in it, believes in one’s own person. I mean that instead of using it as a representation of the Goal, one makes it the goal itself, the center and the god itself. Then the King becomes Tyrant and Man becomes Demon, then representation becomes lie, then dignity becomes pride, then man does what Satan who was Lucifer “bearer of Light” did before him and who took himself for the Light, which is why he was overthrown and cast down.

But when man, on the contrary, accords no importance and no significance to his person, then this person, from being demonic and monstrous as it was, becomes insignificant. It is almost always so in what we call “the world.” People there are what they can be, their amiability does not come from love and does not lead to love, their sensitivity is self-indulgence, their goal does not exist since they are their own goal and I have already told you they are nothing.

What is the person for? To signify. It must be a reminder to all other men of human dignity. We must respect it in ourselves only because of this function. We must never humiliate it in ourselves or in others because of this function, because it is a reminder, because it is a representation of the Higher. It is only for this that it is respectable, and, when it consciously gives the soul its garment of truth, venerable.

Rare and precious in this world are persons. If by chance you meet a person, don’t let them leave without trying to make them a friend. Friendships are made between people. A person is one who creates mannerisms. As I said, it is a work of art, using one’s personhood to communicate with others and express oneself. They accomplish the very difficult and delicate work of composing their person from learned expressions and imitated attitudes. They make external contributions their own and arrange them tastefully, and from such artificial elements common to all like language, manners, and clothing, they manage to create a whole with beauty, balance, originality, and value.

You should know, however, that the drama of the person, whatever their dignity and perfection achieved, is that they must die, that moreover they die without remainder and that finally it is right that they die. The body, you know, dies and rots; it is made of a mortal substance. The person has no substance and consequently falls like an old garment. “The body, this rag,” they say. No, but the person is a rag. And all the trouble that people take to compose an admirable person, to leave in people’s memory the remembrance of a glorious person, all these efforts are lost efforts.

Let us think of God and take care of our soul, and let the person grow spontaneously from within. We will not need to compose a fragile and disappointing masterpiece.

Wisdom has always taught the Person: “Efface yourself”; and simple politeness likewise. The Gospel says: “Whoever exalts himself will be humbled.” Gandhi, after so many others, remarks: “Whoever wants to approach God must reduce himself to nothing.” The mystics of all times cry out: “I am nothing,” and if “I” means “my person,” this is not a poetic figure or passionate exaggeration, but a metaphysically exact statement.

You will say: aren’t the Saints Persons and even Holy Persons? — Yes, and compared to the heroes of novels, tragedies, or epics, their figures stand out more prominently and are more singular. But it’s not because they affirmed or developed their person, that they cultivated, educated, adorned, and exalted it. On the contrary, it’s because they emptied it. For it is not only said: “Whoever exalts himself will be humbled,” it is also said: “Whoever humbles himself will be exalted.”

He who puffs himself up will be found empty, but he who empties himself will be filled. When one stops expressing one’s good or bad character, showing one’s small or great talents, expecting glory and fortune from one’s knowledge and learned abilities, the Holy Spirit will have room to breathe, to resound, to call through him, and if the Person’s role is to signify what surpasses it, here is the glorious fullness of the Person, here the Person becomes Spirit.

I have spoken of the three elements that make up man, but how do these three elements connect? It is through the Self that they are bound. And what is the Self? It is none of these three elements, but it is any one of these three elements. For most men, the Self runs between these three elements like a fly trapped in a glass, hitting the walls at random. It alights now on the body, now on the person, now on the soul. And these are the conditions of the economy of salvation and immortality. Of justice too, for we can be told: you are what you want, you are what you believe yourself to be, you are that upon which you rest. If you want to be the body, you will go where bodies go: to rot. If you want to be the person, you will go where old clothes go, and all your advantages and charms will lead you to nothingness. But if you want to be your soul, your immortal soul, you will go where the soul goes, upward, you will return to God from whom you came. But take care not to let this soul given to you merely pass by, take care not to grow conscious of having a soul that passes and flies away; cling to this soul that is in you, learn to enter into it, learn to be it.

The Priest and the Bank Teller

Two things fill me with admiration: the Priest at the Altar and the Bank Teller.

The Priest ascends to the Altar more richly dressed than an elegant man, better adorned than a king, more gazed upon than a famous actor. He is covered in gold and jewels, eyes and lights turn toward him, incense rises toward him. Whether handsome or plain, he is always beautiful; whether tall or small, he is always great. Yet it never occurs to any priest to think these tributes are meant for him; none struts about, boasts, or blows kisses to the public. The very splendor of the chasuble effaces him.

Well-endowed man whom we rightly respect or admire, look and learn: this is how you should carry your person!

The Bank Teller in his glass booth moistens his thumb, leafs through bundles, pins ten-thousand bills together in tens, pushes packets through the window, stacks others in piles, slides them into drawers or wagons. If he has dispensed twenty million or set aside two hundred billion in the morning, his modest monthly pay remains the same. His heart, his head, his hands retain nothing of the riches he manages.

O Rich Man, look at him, look at him well, and learn!