Approaches to Inner Life, Part Four

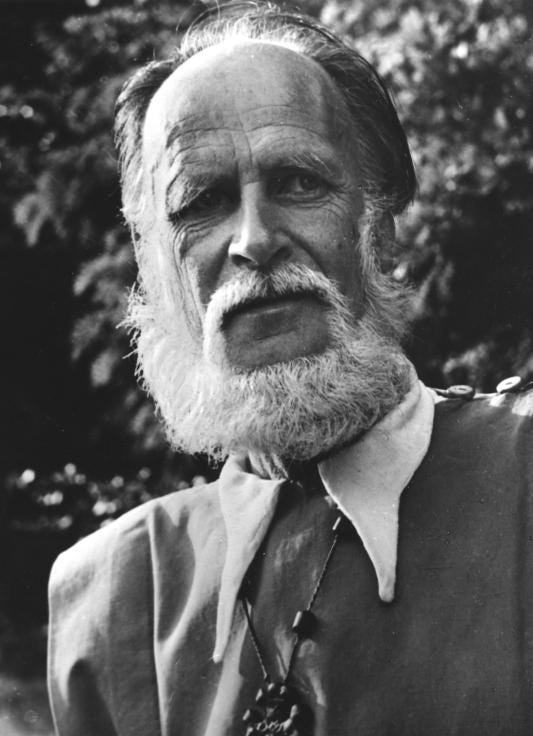

Lanza del Vasto

Translated from

LANZA DEL VASTO, APPROCHES DE LA VIE INTÉRIEURE

ÉDITIONS DENOËL, 1962

Two Friends on a Bridge

“Look at the joy of the fish in the river!” said one friend to another on the bridge.

But the other replied: “How can you, who are not a fish, know the joy of the fish in the river?”

He answered: “By my joy on the bridge.”

Chinese Fable

Of Indifference, Distraction and Recall

This exact definition of the self that I promised you (the one not found in the dictionary) will no doubt be welcome at this extremity:

First Proposition: I am the living unity of the elements that compose me.

Second Proposition: I am none of the elements that compose me.

Third Proposition: I spend my time taking myself for one or another of these elements.

“Living unity of the elements that compose me.” Isn’t there a simpler and more popular way to say this? Yes, with a single word, a very beautiful clear Latin word: the soul.

Will I then say: “I am my soul?”

A Hindu would answer: “Yes, I am it, but I don’t know that I am it.”

But if you don’t know it, how can you say “I am it”?

I can say it well, but I don’t know it by myself. I will know it the day when my soul has become conscious and taken possession of me. It’s in the third proposition that I find myself. I must confess that I am not my soul: I have a soul, that’s all. I am not united with my being and that’s why I float and wander.

Great is the distance between having and being. Let us prepare for the crossing. The formula shows us the precise point of arrival, the direction, the reefs, and we keep good hope.

We still have to learn about contrary winds and currents.

But we haven’t yet overcome our bewilderment at finding ourselves so far from port, if “port” means being what we are and knowing ourselves.

The thing is so absurd that if we weren’t forced to observe it in ourselves and in others as we just did, we would believe it impossible.

How is it that the order of things is thus reversed? By what accident?

Accident is the word! And if its effect is felt in human affairs throughout all time, it’s because it occurred at the origin. This is Original Sin (we’ll come back to this).

But, without going back so far, let us observe, and the observation itself will provide us with part of the explanation.

Let us observe that we spend life turning our backs on ourselves. We have looks, thoughts, and feelings only for other things and other people. How could I know, how could I love someone to whom I always turn my back?

“Come now! You won’t tell me that people sin through selflessness and excessive love of others!”

I haven’t said that: what I’m talking about is their indifference and their distraction. They are quite incapable of loving their neighbor as themselves, since they don’t love themselves.

“And the selfish! Are you going to tell me they don’t exist or that they are rare?”

No, but I say they don’t love themselves at all and I am ready to provide you proof if you lend me one such person. I will lead your selfish person, who you say loves himself so much, into a dark room and I will lock him in. Now, what could be more delightful than being locked in a dark room with the object of one’s love? But what! He isn’t content? What is he crying about? Crying for help as if he had fallen off a precipice? Beating the door with both fists as if he had to flee to escape some beast? Howling in terror as if before a specter, in pain as if being tortured?

Do you need more to note that he cannot “bear himself,” as they say, or stand himself for a single moment? In fact, you will always see him occupied with others, this egoist, clinging to them with all his strength and his full weight: he needs them to keep busy, to mix with them, to amuse himself with them, to be bored with them, to use them for all useful purposes, but above all to escape facing the gloomiest and most sullen of all people: himself.

But of a solitary, you would never say he’s a selfish person, unless you yourself are an idiot.

Have you ever seen a man who loves himself? There are few. You have heard preaching about loving your neighbor. Do they ever preach to you about loving yourself? Do they teach you this truth — that it is the first of duties? It is said: “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” But if you don’t love yourself, how will you love your neighbor?

“As yourself,” it says. Let us insist on the “as.” “As” means “in the same way” and “as” means: “to the same degree.” This means: no more, no less; no less, no more. And there are two vices of love: the less and the more.

And woe to him who loves another more than himself... Don’t think this is rare. All passionate and vicious people do this. They love more than themselves. And they even love their own destruction. They love their ruin. They love the object of their ruin. The object, in all its limitation, or the person in all their object-like limitation, is loved, adored, as an absolute.

This is the beginning of the darkest passions. “Every man destroys and kills what he loves,” said someone who knew about this kind of love. And every man kills himself in this kind of love.

I will point out to you on this occasion that it never happens that a man develops a passion for bread or milk. Why? Because bread is good. Because milk is good. When you’ve eaten bread to satisfaction, it’s done, you stop. When you’ve drunk a bowl of creamy milk, you don’t want any more, and you can’t have any more... But if there is something for which one becomes passionate, it must be an alcohol, a poison, a smoke, or a woman who serves as poison, smoke, and alcohol. We keep returning to it only to struggle against it. One day it strangles you, and through lack of true self-love, you fall victim to it.

Where is he, the one who loves himself, who loves his integrity, his fulfillment, his salvation? What people love is their pleasure, they love their comfort, they love their success, they love everything about themselves except themselves.

“Themselves” — let’s pause on this word. The Hindus say Atmâ, which translates well to the English “Self,” and fairly well to the French Soi. Soi-même would be better, capturing the sense of “himself.” But let’s remove him (lui) and keep only self (même). Thus Atmâ would be the Same, which recalls a major Platonic theme. The Same and the Other are for Plato the two faces of the world, the reverse and obverse of each other, just as we have named the Inside and the Outside. The Same is the same everywhere. It’s the Other that separates and is separated. Myself, yourself, himself — même is the same for all three.

The etymology of the word Même deserves meditation: Memet ipsimum.

Mê: Me. Met: an untranslatable, invariable, inseparable and mysterious particle. Ipse: which, by itself, means “himself.” Ipsimus: more-than-self, a fantastic superlative from a later epoch forged on the model of Optimus: a redoubling that expresses the return of self upon self. The mixture and crushing of the five syllables of Memet ipsimum into one gives Mesme.

Met contains the M of moi and the T of toi as if to say that one has meaning only in relation to the other.

In the second person one says: Tutemet, which would mean you with yourself, and in this case met recalls the mit of the Germans (with). Finally the MT of MeT is perhaps an inversion of the Sanskrit aTMa (Atmâ).

When someone speaks well, listen to what they say, but above all let the words that “want” to say more than the speaker speak within you. Listen to the echoes of their meanings. In their vague noise remains something of the primitive revelation deposited in them before Babel. It’s not always necessary to learn philology for this, it’s enough to learn to be silent. Just as fasting gives us a glimpse of the terrible mystery of nourishment, and vigil the consoling mystery of sleep, so silence introduces the attentive to the depths of the word and through it to the secret of things.

“It is not for love of the friend that one loves one’s friend, nor for love of the spouse that one loves one’s spouse, for love of the child that one loves one’s child, but it is for love of Atman,” as the careless translator of the Upanishad translates “but for love of self,” and all that remains is to speculate and carelessly discuss Oriental wisdom and the little use it makes of love, when what is at stake is that pure charity that the Gospel teaches even more forcefully: “If anyone comes to me and does not hate his father and mother and wife and children and brothers and sisters, even his own life” (Luke 14:26) and “You shall love your neighbor as yourself,” for it is not for attraction to the Other that one loves one’s neighbor, nor through attachment to oneself, but for the love of God.

Now there is something of the Other in me and something of the Same in others. To love is to recognize oneself in others through the grace of the Same. In yourself and in those close to you, you will hate the Other. In others and in yourself you will love the Same.

The cause of all evil is that the Same and the Other mix everywhere, except in God “who is the One, unique and the Same.” To distinguish them is clarity in knowledge and purity in love.

The Same is by its nature love, and failing it means failing love.

But how could you love someone you don’t know? Without even realizing it, you show them your lack of love and your contempt by turning your back on them.

Remember one of your days. The alarm rings, it’s 6:03. You open your eye and think: “Ah! today is Wednesday; I mustn’t forget my appointment at the Café du Progrès at 4 o’clock with that person...” You haven’t even opened your second eye and you’re already projected to the other end of the city and ten hours ahead, with that person! But let’s return to ourselves: quick to the bath. Light breakfast: the newspaper to know what’s happening in Vietnam or Nicaragua. 7:20, I was going to forget the time! A look around before leaving the room. Haven’t I forgotten anything? Portfolio? Tie? Keys? No, nothing. (Yes. What? — Yourself.) But what’s important is not to miss the bus. I catch it just in time. I arrive at the office, I dispatch the mail, I answer the telephone. I receive two visitors. I sign a contract. At noon, I return. I lunch. I start again: the mail, the telephone, the contract, the visit. Finally evening comes. I’m exhausted: let’s go to the cinema to watch scenic views of the Rocky Mountains, like others who put on different lives instead of their own. Very late, I go to bed. I turn off the light. This time, I am alone with myself, or at least I almost was for an instant, but in that instant I fell asleep...

That’s the chain: the chain of duties, work, hassles, habits, necessities, vanities that bind us outwardly, to the Other. But how to escape it? Yes, how to escape from the exterior?

You ask me? Yet it’s simple: by turning inward.

This simple and decisive act is called, in spirit, conversion. Conversion is freeing and detaching oneself from the world and directing intelligence, heart, tastes, and forces toward the Inside.

Toward the “Divine Inside of things,” as the Egyptians say, but first toward the inside of oneself.

We were speaking just now of contrary winds. The strongest in making us drift is indeed Distraction.

There are three degrees of distraction:

First, total distraction: the distraction of the dazed one; he has vacant eyes, a round mouth, he is never where he is. He never thinks of anything. He bumps into everything. He falls down... This is the state of disastrous distraction... Of an angry man, we say he is “beside himself.” The distracted one spends his life being beside himself, without any anger. This state of distraction, of disorder, of incoherence, of perpetual foolishness, is not a pleasant state — it is the dust of the soul, it is the corruption of intelligence — but corruption is too humid, too odorous: so let’s say “dust.”

Then there is the pleasant distraction of one who amuses himself by being distracted, who takes pleasure in it. Distraction, distractions... diversions... are much sought after because it’s the same word dis: outward and at random, and vertere: to turn. One distracts oneself whenever possible, but one cannot always, unfortunately; one cannot amuse oneself all the time; one must try to be serious.

Finally there are serious distractions. They’re called business. Or even studies. If you seek the reason for this great zeal that people have for studies or for business, don’t think it comes from a love lost in duty, or from an immense effort to conquer laziness. No! You’ll notice it the day they retire; they no longer know what to do with themselves... These same-selves that they never occupied — that’s what falls into their laps... They will soon take up some illness, the only distraction serious enough to replace their former work.

If Distraction is a malady of the Spirit, how can one cure it except through Attention, through Inner Attention?

But when, closing my eyes, I turn my gaze inward, what do I see? — Nothing, blackness. That’s why I’m frightened or bored, that’s why I flee.

Well then, tell me! Has it happened to you, leaving a crowded street, to enter a cellar? What do you see in the cellar? Blackness. No, not even blackness, but rather a fog of luminous particles dancing before your eyes. And how long will it take you to see the blackness? Twenty minutes. And if there happens to be a treasure in the cellar, how long to see the treasure glinting? An hour.

But who among you has remained, for an hour, with gaze fixed on the inner darkness?

Do this and you will see!

I’m not telling you what you will see and I’m not asking you to believe me. I’m not asking you to believe what you have heard or read, but to go see and come back to tell what you have seen!

Certainly, to stay for an hour straight before oneself in darkness will not be the first step, for it’s too difficult. One must approach it little by little. The first step will be to overcome the “contrary current” of the chain, the “contrary wind” of momentum, of dispersion, of total dissipation, which is the state of non-being. To be dispersed is to be as if not being. The first exercise that we propose to you, friend pressed and burdened with very important matters, will not ask an hour or a half or a quarter, but three minutes; and what busy person doesn’t take three minutes to wash their hands? Still, three minutes may be too much; let’s cut it into six: Six times during the day, three times in the morning, three times in the afternoon, hold yourself in suspension.

Stop. You’re in a hurry? All the more reason to collect yourself! You have things to do? Stop, or you’ll do foolish things. You must take care of others? All the more reason to start with yourself, lest you do harm to others.

So then, unwind, relax: every two hours, stop for half a minute. Put down your tool. Hold yourself upright. Breathe deeply. Draw your senses inward. Remain suspended before the inner darkness and void. And even if nothing happens, you will have broken the chain of precipitation. Repeat “I recall myself, I collect myself.” That’s all. Say it to yourself, but above all do it. Recollect yourself, as is said so strongly: To recollect is to gather all the scattered fragments of self that remained caught here and there. Answer like Abraham to God who called him, answer “Present!” (Adsum!)

So remain present to yourself and to God for half a minute.

Suspended at the opening of the inner well.

It’s unlikely that one would make a deep dive into the mystery of self in so little time, but it’s not impossible with God’s grace. However, if nothing else happens during this moment of suspension, we will have broken the chain of events that holds us prisoner, we will have broken it in six places and begun deliverance. Moreover, if we want not only to recall ourselves to awareness, but also to remember that we must recall ourselves every two hours, we will need to practice a latent and continuous recall that will underlie all the actions and thoughts of the day.

Recall is the first step toward self-knowledge, or awareness.

But how can we call this a first step when we have already spoken of “The Three Steps,” and this is not one of the three?

The Three Steps we discussed (“I am not my body,” “I am not my character,” “I am not my thought”) made us descend to the bottom of original error; they made us probe unknowing.

And certainly, nothing is more necessary than this plunge into the night. For man is incapable of truth until he recognizes the error concerning his being.

To recognize error is already an opening to truth and thrust toward it.

For one cannot go beyond nothingness. And in darkness one cannot remain.

So recall is the first step in reverse, the most humble degree of the ascent.

This first step, though small, is decisive and of infinite consequence because it is the first, and without it the others are impossible or illusory.

We have seen that everything begins with the head. The beginning of the head is the eye. The beginning of thought is the gaze of intelligence or Attention.

Recall is the conversion of Attention, the return of the gaze.

To aim at the target, Archer, your two eyes are too many: close one! If the target is within, close both and shoot!

The first step on the right path. And the path is good, even if it is uphill, rocky, and above all narrow. Narrower than a needle’s eye: neither loaded camels nor rich intelligences can pass through there, the exact and strict point that is the true self!

But beyond all opens and turns to light. Know this — I invite you to a great adventure!