Last night my wife came to me upset after having put our little to bed; she’d had an experience that I won’t describe in detail, but suffice it to say that it was eerie. As we talked it over, some thoughts coalesced in my mind. I’d spent the previous morning (Saturdays are my day for a few solid hours of reading in a silent house before the rest of the family wakes up) with Terryl Givens’ account of the doctrine of souls’ pre-existence, When Souls Had Wings. Givens is a good writer and an erudite scholar, and I recommend him wholeheartedly to all; it will help you get over any merely polemical negativity you harbor for Mormons.

Somehow the conversation and my train of thought converged, as they often do. I began to feel my revulsion for the entire universe of speculative thought — for what I think St Paul was referring to when he mentioned fables and endless genealogies, which minister questions, rather than godly edifying which is in faith. I believe, as I have read commentators say, that these endless genealogies refer to the various impenetrable systems of emanations in the Gnostic cosmologies that were already circulating in the milieu in which the Gospel was being preached. Here is where I reveal my inner evangelical fundamentalist: ultimately I think there is no essential difference between these speculative elaborations and the speculative elaborations of metaphysicians. There is also no essential difference between those metaphysical speculations and the world of fear and superstition that accompanies engagement with occult or paranormal phenomena. The speculations are of course more systematic, more educated, more articulate. But they are still a form of sorcery, of magic in the sense in which the tradition correctly condemns it: they place fundamental trust for the establishment of security on the workings of our own mind, on forces arising in and from our own spoken or willed interiority.

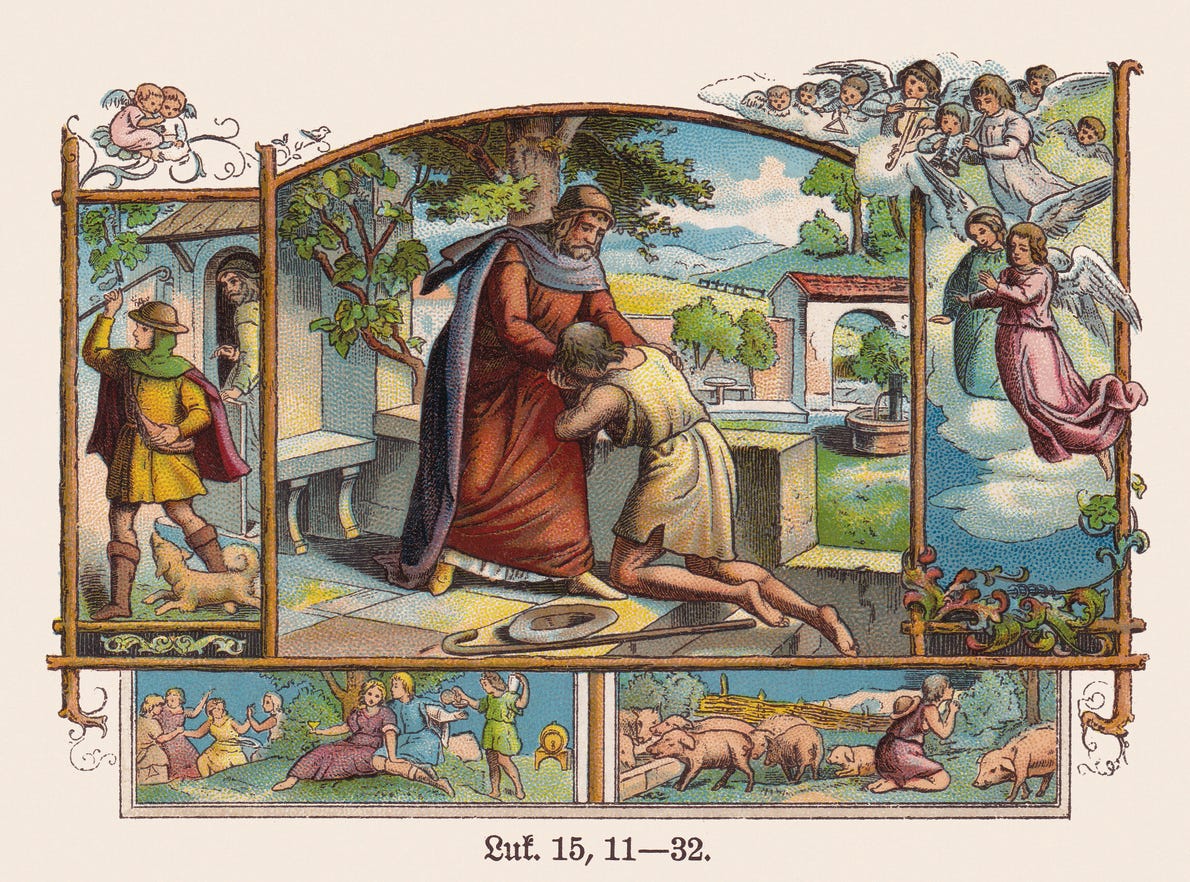

I think Jesus is perpetually taking up the sword and cutting these Gordian knots open; at least, this to me is the existential effect of the Gospel. When I sink myself into these imponderables with what is, indeed, an essentially irreproachable desire to know — after all, isn’t our mind made for knowledge? — eventually I look up, like the young man in a famine-stricken land who suddenly realises that he can simply repent and go home to his father’s house. I suddenly remember my thirst for the transparent, sparkling water welling up unto eternal life; my hunger for the bread of the Word that satisfies.

Then I turn again to the ascetical tradition, seeing in it a golden thread from which I can easily be distracted. That thread is woven in with much else that is dubious and troublesome, with a crypto-Manichaean hatred and fear of the flesh, embodied existence, sensuality, sexuality. Who can cast aspersion on that Manichaean tendency, in the end, of course? Who hasn’t looked nakedly on the agony of life on this earth and groaned with the great Stoic emperor, How long, then? And yet my heart rebels at the tension: I cannot simply accept the grim and dismal rejection of embodied life, but neither can I revel and sport in the depths of creation’s delights while the dark realities sit silently just out of the ring of firelight. O wretched man that I am! who shall deliver me from the body of this death?

I know the deep resolution of this tension; it is Pascha; I long for it every year; it is the shining summit of my life to which the grace of the Spirit in the Church brings me. But it is not a summit where I can dwell. It is when I descend from these heights that I grasp again the golden thread of the ascetic tradition.

What is it?

Here is where my advocacy always becomes a mute gesture. I have to point. Mostly, I point at the lives of ascetic saints. But there is so much dross there, so much useless, superficial sensationalism that in older days apparently must have been effectual as an appeal for veneration, admiration, and imitation, but today more often than not simply serves to repel. He spent his life standing atop a pillar! Ah, then he was a deranged madman? Let’s be honest: who can hear this? And let’s not pretend, with the rad trads, that we can mystically teleport ourselves into that age — that age is gone. And it is gone for a reason. The rad trads always want to forget that there was a reason the people of the past embraced the march of “progress” so-called. Perhaps those mystical revanchists need to spend some days in unremedied contemplation the next time they have a toothache, when the pain becomes so severe they can’t think, to become a little more honest. (By the way, the same goes for their critique of feminism. Some conversations with old women are helpful in this regard.)

Again, then — the golden thread of asceticism. If it is not the advertising slogans made to dazzle the men and women of a lost time, what is it? Where can it be seen?

In the lives and lore of some ascetic saints, beneath the sensationalism when it is there (but in modern accounts, often, it is not there, and this is why the saints who are close to us in time and space are so important for us), there is something pure and limpid: there is a humble heart content not to know, content to throw itself on the Lord and cry Have mercy on me! Our minds may indeed be made to know, but if I can put it this way: the path to knowledge is not to seek knowledge. Our minds’ capacity to know shall be satisfied some day — but today is not that day. And they cannot bootstrap themselves there with a pursuit of knowledge secretly fueled by the fundamental fear that accompanies the practical rejection of God in an intellectual and spiritual self-reliance.

Now: this does not mean a wilfully ignorant, fundamentalist reification of revelation or of the authority of the Church, either. Much that comes to us in “revelation” and “tradition” is, as Nikolai Berdyaev says in Truth and Revelation, merely sociomorphism and cosmomorphism, a projection of our own human, all-too-human desperations and fears and hungers into a false certainty that ends up being tragically fragile and unreliable. I can practically taste the fear and self-delusion whenever I meet someone wholly committed to any dogmatic or metaphysical system, even if it is officially sanctioned by some ecclesial authority or other. I taste it the way you can pre-taste the blood in your mouth when you meet someone who’s obviously hell-bent on punching you in the face. (I hope you’ve never had that experience.) When I talk about an epoché with regard to metaphysical speculation, I’m talking about the Fathers, too. I’m talking about the Tradition, too. I’m talking especially about the attitude that appropriates the Fathers and the Tradition — or rather, appropriates our particular parochial approach to them — as weapons for a fight. God save us!

Faith is not a system of ideas. The Gospel is not an ideology. The life of the Spirit is not a bureaucracy or a creed or an enchantment.

As far as I can see it and say it, the Gospel, as it is transmitted existentially and experientially in the golden thread of asceticism, is first of all an utter simplicity. It is laying aside the all-too-human attempt to know by our own power what we cannot know by our own power. (Re-read God’s response to Job out of the whirlwind — deeply unsatisfying as it is.) It is contentment to be small, to be ignorant, to put all our business aside and set out on a pilgrimage, to simply leave all that hunger for knowing behind.

Yes, when with our minds we press down into the Gospel itself, even there, we find endlessly fascinating material. One strand that fascinates me: the Aramaic roots that underlie the Greek text of the Gospels that we have, and what they reveal about Jesus’ concrete historicity, the resonances they open up within his teaching that have been obscured by the overlay of Hellenism. But on the contrary: also the examination of the entire, endlessly complex cultural and religious background of the Gospel’s setting — a background which Margaret Barker has revealed as far stranger and richer than the vastly oversimplified cartoon sketch that comprises the common understanding of that milieu.

So much for all of that. It’s the same territory, endless genealogies. I say that with the simple consciousness that however far down that path I go, I eventually find myself a starving swineherd looking longingly at the food his pigs are eating, realizing that I can simply return to my Father’s house. This, after all, has turned out to be the final destination of the “quest for the historical Jesus,” at least for those who are not inclined to set up a permanent residence in the far country of hunger and penury.

Asceticism in essence is that return, in simplicity and compunction, penthos.

And concealed within that utter simplicity of repentance and renunciation and pilgrimage, as its burning heart, even if the burning is mere coals — there is love. This is Jesus’ Way.

Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind. This is the first and great commandment. And the second is like unto it, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself. On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.

The great saints whose lives kindle (or rekindle) in us the desire for this Way are normies. They live, as Jesus did, not in the world of metaphysics, but in the world of bread and salt and water and candles and grain and wine and sheep and lepers and the blind and newlyweds.

These are the ones I love most, in the end — not the high mystical theologians. To be honest, I don’t know quite what to make of the latter. But I know that seizing on their theology before understanding what lies beneath and before it, before reaching the point where hearing the Beatitudes at the Divine Liturgy brings me to tears, is delusional, indeed, it is a path to perdition.

It’s easier to be with the normie saints. The ones who would smile and nod when you ask them perplexing theological questions, when you propound esoteric theories and elaborations, and walk over to the samovar to pour you a cup of tea, and tell you about the frogs who have taken up residence in their little monastic garden, and with whom they sing the psalms. (If you want to read that one, go find a copy of St Paul Florensky’s Salt of the Earth — and be sure to read that book before you try to read The Pillar and Foundation of Truth. The confessor Serge Fudel said, “In all his mathematics, Father Pavel was building a fragrant temple for prayer.”)

This finally is the answer to modernity. This is what is drawing me towards a life in the mountains without computers or electricity. This is what makes me want to pray, to bake bread, to write, to play with my daughter, to garden, to make love with my wife, to drink tea in the morning silence, to read the Gospel and the Prologue of Ochrid and the psalms, to wonder what I can do today to take another step on Jesus’ Way.

This post was written without using AI.

I think the paradox, of course, is that unknowing is also a type of knowledge: it takes a substantial amount of knowledge to renounce knowledge and evade the Dunning-Kruger trap. Given that ideology is the default fallen human setting, it takes actual mental work to escape it, work premised on the gnosis that ideology is a lie.

This is well said. I encountered a similar ‘prodigal’ moment about three quarters of the way through “Lost Christianity” by Jacob Needleman recently. What started off as a refreshing appreciation for the practice of contemplation and the cultivation of awareness of God, morphed into - largely via the verbosity of one Fr Sylvan (who I think is actually just Gurdjieff in monastic garb) - endless and opaque speculation on the nature of the soul and how one comes to acquire one. I found myself getting more and more frustrated as the complexity mounted. Putting the book down and returning to the simple and yet profound practice of the Jesus Prayer proved to be my return into the arms of the Father.