The New Theology: Part One

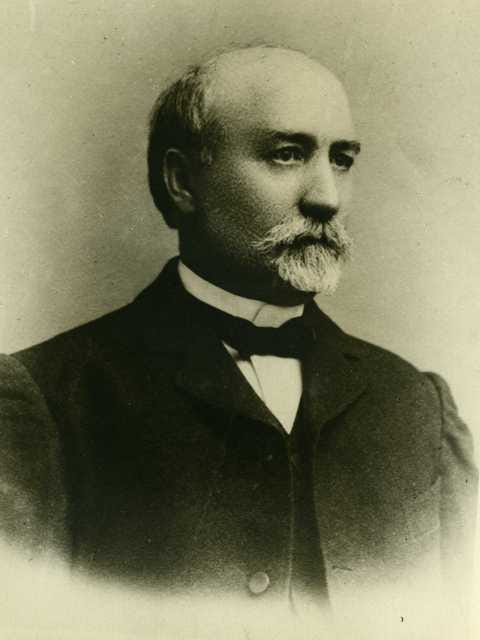

Mikhail Mikhailovich Tareev

Mikhail Mikhailovich Tareev (1866–1934) was a distinguished Russian Orthodox theologian and professor, best known for his reformist approach to theology. Teaching at the Moscow Theological Academy, Tareev became a key figure in early 20th-century Russian theological thought. His theological innovations were met with mixed reactions, making him a controversial figure in Russian Orthodox theology. While he sought to reform and revitalize the field by introducing a more experiential “moral-subjective method” alongside traditional dogmatic theology, his ideas often clashed with established Orthodox positions. Tareev’s emphasis on integrating subjective, lived experience into theological study was seen by some as a refreshing and necessary evolution in a field dominated by abstract scholasticism, but others viewed his approach as too radical and potentially destabilizing to traditional Orthodox theology.

His critiques of the rationalist and scholastic tendencies within Orthodox thought, and his call for a more personal and spiritual engagement with Christian Truth, set him apart from many of his contemporaries. Despite his loyalty to Orthodox dogma, Tareev’s approach was sometimes perceived as challenging the rigid structures of Orthodox theological education. As a result, while his work was welcomed by some, others considered it modernist or un-Orthodox, contributing to his controversial reputation within the Russian religious establishment.

Tareev advocated for an approach that embraced both dogmatic theology and moral theology (нравственное богословие) as complementary yet distinct sciences. While dogmatic theology focused on objective truths, Tareev believed moral theology should engage with Christian truths through the lens of subjective human experience and spiritual insight. He sought to reinvigorate the spiritual life of the Church by reconnecting theological study with personal faith and lived religious experience.

This emphasis on the balance between objective dogma and subjective experience set him apart from more critical theologians, as his approach arguably aimed at enriching the tradition rather than abandoning it. Tareev’s work represents a unique attempt to harmonize the intellectual and spiritual dimensions of theology, making him a pivotal figure in the 20th-century revitalization of Russian Orthodox thought, albeit one neglected and largely unknown outside Russia — not least because his remarkable theological project coincided with the utter collapse of the traditional Russian Orthodox world in the chaos and destruction of the Revolution and the terrors which followed.

Note: The Russian word нравственный carries nuanced meanings beyond simply “moral.” The root нрав means “temper,” “disposition,” or “character.” Thus, нравственный can evoke a sense of personal disposition or internal character in addition to the broader ethical or moral implications. This resonates with a more intrinsic or character-based understanding of morality, where ethical behavior is not merely about external rules but deeply connected to one’s inner nature, temperament, or spiritual makeup.

In Russian intellectual and spiritual traditions, particularly in the works of figures like Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and the Russian Orthodox tradition, нравственность often refers to moral character shaped by faith, suffering, or conscience. It points not just to abstract moral principles, but to how these principles are lived out in the complexities of life and personal experience, making it a deeply existential term.

In the context of Tareev’s work, where he contrasts dogmatic (objective) theology with нравственное богословие (moral theology), the term likely carries these deeper resonances of an experiential, character-based approach to faith and Christian truth, rooted in subjective human experience and personal spiritual struggle. This reflects a profound understanding of “morality” as something integral to one’s being, rather than simply adherence to external ethical standards, and his advocacy of a “moral-subjective method” in theology should be read in this light.

Introductory lecture delivered in September, 1916

There is a custom among you: for the first lecture of each year to gather in numbers incomparably greater than those who attend lectures throughout the year. It attracts not only students of the “current” course, but also those from other courses. Something special is expected from the first lecture: it should not be just one among many lectures that refers to a series of other readings — it should present itself as something whole, replacing the entire series of readings, something remarkable, exhibition-like, and showy. I do not like this custom, and I have never conformed to it. The introductory lecture should introduce listeners to the course of readings; it is addressed only to those who will attend the subsequent lectures; it is not suited to an unnaturally elevated tone; it cannot help but disappoint lovers of spectacle. In my view, it is not normal for the first lecture to be more interesting than the following ones; on the contrary, it is natural for interest to increase as the course progresses — for regular listeners, so that early, hastily achieved effects give way to gradually unfolding content. Therefore, the abundance of listeners at introductory lectures has always disconcerted me.

But this time, I want to take advantage of your one-time gathering and offer you a topic that, while retaining the character of an introductory lecture, would also hold significance for casual listeners. I want to succinctly, within the narrow confines of a single lecture, outline for you the main features of my theological thought, indicate the primary direction of my religious ideas, and acquaint you with the type of my system, its method, foundational principles, ultimate tasks, and highest aspirations.

The official title of our department is “moral theology.” However, I do not recognize moral theology as it is outlined in the traditional seminary curriculum, as presented in seminary textbooks, and to some extent, in academic courses. Much has already been said about the miserable state of this field; I consider this science, in its ideal form, to be a fiction, a stillborn invention of scholasticism, some pitiful misunderstanding. Nevertheless, the place occupied by moral theology is a holy place, as this discipline addresses profound questions and boundless perspectives.

So, what do I place in the stead of moral theology? Two disciplines: one taking the place of moral theology as a higher discipline, and the other as an educational discipline.

The higher, creative discipline that, according to my plan, should replace traditional moral theology can be constructed either within the narrow, specialized framework of a particular science or with the full breadth of a philosophical system. In the narrow, specialized sense, as a distinct theological science, this higher discipline is the moral doctrine of Christianity. It should stand alongside dogmatics, that is, the dogmatic doctrine of Christianity, and be proportionate to it in scope. All of positive theology should be divided into two parts, and its entire domain should be shared between two sciences: the dogmatic doctrine of Christianity and the moral doctrine of Christianity.

The distinction between the division of positive theology that I propose and the traditional division is that, up until now, the division between dogmatic theology and moral theology was a division of the very subject of theological science itself. One part of the Christian religion, one of its domains — let’s say the theoretical part — was assigned to dogmatic theology, while another part — let’s say the practical part — was assigned to moral theology. For the old theologian, each theological issue bore the mark of belonging to one or the other domain, to one or the other science. The question or doctrine about Christ was considered a dogmatic issue, belonging to the realm of dogmatic theology, while questions about faith, hope, and love, or about fasting, were considered practical matters, belonging to moral theology.

In this objective sense, the division of positive theology was not exhausted by dogmatic and moral theology, as other theological sciences stood alongside them — liturgics, canon law, etc. Furthermore, it was deemed entirely appropriate to judge the importance of different parts of the Christian religion, which were divided among various theological sciences, particularly between dogmatic theology and moral theology. It was specifically the case that the subject of dogmatic theology was always considered superior to that of moral theology. Correspondingly, dogmatic theology itself was regarded as higher and more important than moral theology. Dogmatic theology dealt with the doctrine of God Himself, while moral theology dealt only with humanity; dogmatic theology discussed objective salvation, while moral theology concerned itself merely with its subjective appropriation; dogmatic theology focused on Christian Truth itself, while moral theology was concerned only with its practical application.

This was the division in old theology. However, what I mean by the division of theology into the dogmatic doctrine of Christianity and the moral doctrine of Christianity is something entirely different.

When I speak of the division of positive theology into the dogmatic doctrine of Christianity and the moral doctrine of Christianity, I do not mean different parts of the Christian religion, nor different aspects of the subject of theological science, but rather a method — different methods of studying the unified Christian religion. The dogmatic doctrine of Christianity is the doctrine of Christianity using the dogmatic, that is, objective, method, while the moral doctrine of Christianity is its study through the moral method, that is, the moral-subjective, or simply subjective, method. It is especially important to emphasize the originality of the moral-subjective method because the dogmatic doctrine of Christianity remains the old dogmatics, while the moral doctrine of Christianity, meaning the doctrine of Christianity according to the moral-subjective method, is something completely new, unheard-of in theology, and in any case, it is entirely different in nature (toto genere) from the old moral theology, having nothing in common with it.

In the old theology, from the perspective of the subject matter, only dogmatics existed. There was a time when there was no moral theology among the theological sciences at all, when only dogmatics was taught in religious schools. To use the words of [St] Philaret [Drozdov, the Metropolitan of Moscow, reposed in 1867]: “Only dogmatic theology was taught, in a method that was excessively scholastic; hence the knowledge was dry and cold.” Theology was concerned solely with dogmatic, abstract questions. The old theology was not only dogmatic in terms of subject matter, but also exclusively objective in its method. It dealt only with dogmatic issues and unconsciously adopted an exclusively objective approach to religious truth. It raised only dogmatic questions, to which the objective method corresponded, and it could not imagine any other method than the objective one.

Over time, “practical theology” or “active theology,” which later became moral theology, was introduced into the curriculum of religious schools. It is important to note that even until recently, moral theology was treated with extreme neglect in the old theology. Even more significant is the fact that moral theology was developed using the same objective method as dogmatics — the only method recognized by the old theology. In moral theology, the element of moral teaching, edification, and preaching was strong, and it was believed that the presence of this element would give moral theology a specific character, distinguishing it from dogmatic theology. However, moral instruction does not constitute a science, and no matter how prominent it was in moral theology, it cannot be used to judge the method of moral theology.

As for what was scientific in moral theology, the moral problem in the old theology was solved only by the objective method and discussed only from the objective side; the doctrine of morality was by no means a moral-subjective doctrine of Christianity. Therefore, for the dogmatic doctrine of Christianity, it is possible to retain the familiar and customary objective method — in other words, it is possible to preserve it in the form of the old dogmatics; whereas for the moral doctrine of Christianity, a new, moral-subjective method must be postulated.

A significant reform is also required for dogmatic theology. The old theology applied the objective method — the only one it knew — in a scholastic manner, or more accurately, a rationalistic and scholastic manner, as scholasticism is a poor form of rationalism. Theological scholasticism derived all its content from reason and followed the worst possible taste, clumsily and coarsely preoccupied with hollow, sterile abstractions. Since the era of scholasticism was a time of exclusive cultivation of dogmatics, scholastic habits became ingrained in dogmatics, and to this day, it remains a breeding ground for scholastic “bacteria.” It requires great effort to reform dogmatic theology, to cleanse it of its scholastic heritage, and to turn it into a genuine science — specifically, a historical study of dogmas. In parallel, moral theology should become — in a strict, specialized scientific sense — a study of Christian life, of Christian experience.

Yet a dogma is nothing other than objective truth, and a dogmatic worldview is nothing other than an objective doctrine of Christianity. Cleansing dogmatics of the scholastic tradition does not in any way undermine the objective method of dogmatic theology; dogmatics retains the well-known, habitual objective method. Although its peculiarities are quite clear when compared with the new moral-subjective method, and although only the distinction of methods makes possible the very statement of the question about method (about the methods of theological thinking), the question about the moral-subjective method is new. The very question of methodology in theological thinking boils down to the question of the moral-subjective method, raised in connection with the moral doctrine of Christianity. The theological task of our time is to clarify that the moral doctrine of Christianity is the doctrine of Christianity through the moral-subjective method, its consideration from a moral-subjective perspective, and that the moral-subjective method is a unique and original method of theological inquiry.

The theological task of our time is to clarify that the moral doctrine of Christianity is the doctrine of Christianity through the moral-subjective method, its consideration from a moral-subjective perspective, and that the moral-subjective method is a unique and original method of theological inquiry.

Moral theology, or the doctrine of Christian life (to put it more traditionally — moral theology), gains full legitimacy as an independent discipline by virtue of the fact that it applies its own unique, specific method — the moral-subjective method — to the study of Christianity and the exploration of Christian Truth. It cannot be merely a part of unified theology, specifically of dogmatic theology, because it fulfills a task that dogmatic theology cannot accomplish. It is not simply a secondary, practical application of Christian Truth, as it aims at knowing this Truth — just like dogmatics — but through a different method, distinct from the objective-dogmatic one. Therefore, it occupies a place alongside dogmatics in a completely different sense than other theological sciences such as liturgics and canon law. Together with dogmatics, the two form a unique, privileged, aristocratic pair, since there are only two possible methods in the study of Christian Truth: the objective and the subjective methods, which are applied in dogmatic and moral theology, respectively.

Only these two branches of theology, out of all theological sciences, aim at the knowledge and positive exposition of Christian Truth, and there should be no more and no fewer than two of them, corresponding to the two methods of knowing Truth.

(We say this while omitting artistic knowledge, both because there is nothing comparable to it among theological sciences, and because artistic creation differs entirely from both objective and moral-subjective knowledge. Thus, there may be objective “philosophy” and spiritual philosophy, but there is no such thing as artistic philosophy. Aestheticism is a direction either of theoretical or of practical philosophy. To put it differently, when speaking of two paths of knowledge, we initially include moral-spiritual and aesthetic knowledge under subjective knowledge, but then, for the reason mentioned, we separate aesthetic knowledge and leave only moral-subjective knowledge under the name of subjective knowledge.)

Dogmatic theology and the moral doctrine of Christianity differ from each other in method, not in subject matter. Both theological sciences have the same subject: the whole of Christianity, the whole of Christian Truth. The moral doctrine of Christianity deals with the same material as dogmatics but approaches it from a different, moral-subjective perspective.

Christ and the Holy Spirit can be the objects of both dogmatic theology and the moral doctrine of Christianity. Dogmatic theology teaches about Christ and the Holy Spirit abstractly, detached from human experience, independent of the human point of view — much as physics, physiology, or pathology describe phenomena without reference to subjective human states like sensations of warmth, cold, satiety, or pain. It considers Christ and the Holy Spirit as they exist in themselves, primordially and invisibly, and what they objectively accomplished for the world and humanity.

In contrast, Christ and the Holy Spirit, as historical and psychological facts, as part of human experience, as concrete historical-psychological realities, as values for humanity — these constitute the theme of the moral-subjective doctrine of Christianity. It studies them within the very atmosphere of historical and psychological reality, in the warmth and richness of human experiences, inseparably surrounded by visions, encounters, sensations, and states of the believing soul. In the same way, the entirety of Christianity can be observed from a distance, from the outside, with a cold mind, more geometrico [in the manner of geometry], expressed in abstract formulas — this would be the dogmatic doctrine of Christianity. And it is possible to view the whole of Christianity exhaustively, without omitting anything, from within the human soul, to look at it with intimate vision, to approach it from the side of spiritual sensations, spiritual taste, to understand it with the heart, to comprehend it by direct faith, to evaluate it experientially — and this will be the moral-subjective doctrine of Christianity. There, the teaching focuses on how God created and redeemed man; here, it is about how man came to God and found his salvation, his good. There, Christianity is presented as an idea about man, as a concept; here, it is also presented as human experience, as personal history.

It is possible to view the whole of Christianity exhaustively, without omitting anything, from within the human soul, to look at it with intimate vision, to approach it from the side of spiritual sensations, spiritual taste, to understand it with the heart, to comprehend it by direct faith, to evaluate it experientially — and this will be the moral-subjective doctrine of Christianity.

The old theology knew these terms — objective and subjective. It taught about objective salvation, which included Christ’s satisfaction of divine justice, and about subjective salvation, as the personal appropriation by the individual of what Christ had already accomplished for him. However, this usage of the terms is not what we are talking about. In the old theological teaching about salvation, the terms “objective” and “subjective” were applied to parts of salvation that were temporarily divided, much as the preparation of meals in the kitchen is separated from their consumption by guests in the dining room. The methodological use of these terms has a different meaning: methodologically, objective and subjective approaches do not divide themselves according to the time or spatial existence of their theme, but apply equally to the same theme, which is fully addressed by both.

Every moment in the life of Christ, every act in His work, every manifestation of the Holy Spirit, every point of Christian teaching can, in its indivisibility, be comprehended and expressed both objectively, in concept, and subjectively, in its concrete content and in its soul-value.

There are two possible methods for knowing Spiritual Truth: the objective-dogmatic and the moral-subjective, and these correspond to two positive theological sciences: dogmatics and the moral doctrine of Christianity. Can it be said that one of these sciences is higher than the other? No. These are not two stages of the same knowledge, where one is lower and the other higher; these are two equally valid approaches to knowledge, each suitable for its purpose. Dogmatics provides the objective, abstract understanding of Christianity, while the moral doctrine reveals its subjective, emotional, living, experiential evaluation. Depending on whether objective, abstract knowledge or internal comprehension is required, one or the other method should be applied, and one should turn to the corresponding science. Neither can give what the other provides, and neither can replace the other.

As sciences, dogmatic theology and the moral doctrine of Christianity each fulfill their own role in the knowledge of Christian Truth, which turns out to be twofold. As sciences, they are equal in rights, equally valuable, and mutually independent.

Are you translating these from Russian yourself?