A Brief Theological Interpretation of the Nation

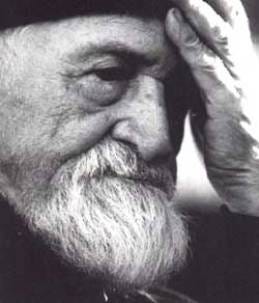

St Dumitru Stăniloae

Translated from Scurtă interpretare teologică a naţiunii, published in Ortodoxie şi românism, Sibiu, 1939.

Everything in the world is God’s handiwork. The rightly-understanding Christian despises none of the components of the cosmos, but in all things sees the shining forth of divine glory and wisdom. Isolation from the world and contempt for it, withdrawal into self and closing the windows toward the world, are not characteristic of authentic religious experience. The withdrawal of Orthodox ascetics has only a methodological significance: it aims only at the restoration of personality, the rediscovery of the spiritual center from which one can then view the world and direct loving actions toward it. Orthodox asceticism derives from the idea that man is the center and master of the created world, but through sin has fallen into slavery to the world, slipping from the Archimedean point from which he is capable of overseeing and mastering the world, into the horizonless and freedomless machinery of natural necessity. The restoration of the commander to the command post, not his isolation from the world, is the aim of Christian asceticism. All the saints, that is, those who have surpassed the stage of methodical withdrawal, have worked in the world with boundless love and rejoiced in all they saw with childlike innocence. St. Seraphim of Sarov, the great Russian ascetic and saint of the 19th century for example, called everyone who came to him “my treasure” and “my joy.” “These appellations were not simply expressions of joy from a soul transfigured by asceticism: for St. Seraphim the image of God was revealed in every person and this image constituted for him a real and true ‘joy in the Lord.’”1

Truly wonderful and sublime is the world with all that constitutes it. It is true, God did not create it to fulfill Himself, to perfect His internal life which would not have been complete without the world; creation was not a natural necessity for the divine being. But this freedom of God from natural necessity does not mean that the world was created accidentally or arbitrarily, like a toy invented ad hoc by a bored God, from a momentary caprice of omnipotence. The world is not a worthless accident, product of a fantasy or momentary whim, but has a deep foundation in God and realizes His eternal idea.

This entire world is, in its content, eternal. All things in it are eternally conceived by God; the ideas of things in the world constitute the material of God’s essential thought, are inseparable from His being. The Russian theologian [Sergius] Bulgakov calls the organism of divine ideas, this internal divine life, the self-revelation of divine being in itself, uncreated Sophia. And of the world he says that it is exactly the same Sophia, but in created form.

The cosmos is still the divine world, but placed in a state of becoming outside of God. “The creation of the world consists, metaphysically, in that God has put His own divine world in the form of becoming.”2

But between the created and uncreated world there is not only the closeness between copy and model, but an even closer one. The divine world is not a static model, but a complex of dynamic forces. They activate from the metaphysical boundary of things, driving their development toward the form which is found realized in them from eternity. If a person or plant develops in a certain way and to a certain degree, this is not due only to blind chance and external influences, but to the force-model which, from beyond the metaphysical boundary of that person or plant, has penetrated into it and orients its organization and assimilation of external influences in a predetermined direction. Even more: every person or thing contains its complete form at each moment of development, only in diverse stages of unfolding. The child implies within itself its complete form from deep old age, and likewise in its mother’s womb. One can go back thus to the initial, limiting point: in the minute embryo is included the perfect form of the specimen. And beyond the embryo in its initial stage, beyond not in a spatial sense but metaphysically, is another model, the spiritual model, the force-model from which the created embryo takes its power.

Therefore, the spiritual model, the force-model, however gradually it leads the development of a living specimen, nevertheless at the initial moment, at the moment of creation, made a huge step, did essentially everything: it brought forth into created and hypostatic manifestation a thing which is its image.

This mystery appears in all its depth when we meditate on the proper creation of the world. Through the action of the force-models, the created germs of their children suddenly appear; their images appear suddenly, undeveloped. These images are not an irradiation of the models, but neither is irradiation absent from the images, for a communication of force from models to images must take place. A mysterious transcensus occurred here, a passage from one plane to another entirely heterogeneous plane.

But in the embryo of a specimen is contained not only the complete form of that specimen, but also, as potentials, those of the specimens that will descend from it.

Thus, creation proper did not consist in a showing of the world in its fully developed form, with all the species and varieties of things in it. God created only the seeds of things, but in these seeds are potentially contained all their subsequent forms. This development occurs through a collaboration of God as provider with the world. What is from the beginning in God fully revealed and developed, in the world appears gradually, in time. The development of the world is a revelation in time of forms that exist eternally.

Regarding man specifically, God created Adam and Eve at the beginning. But in them were potentially contained all nations. These are revelations in time of images that exist eternally in God. At the foundation of each national type acts an eternal divine model which that nation has to realize within itself as fully as possible. I do not know how far laboratory research has progressed regarding the distinction of blood in different races or even peoples. But even if the differences were materially too minute to be detected with instruments so far, it is self-evident that just as there exist other quite remarkable anatomical differences between different races, there will also exist differences in the blood (without extending far enough to break the unity of mankind) which underlies the organization of the skeletal system, just as it is self-evident that physical differences correspond to differences in psychic and spiritual powers, which are the ultimate immanent forces that guide the organization of the body.

In only one case would nations not be from God and we would have to fight against them: when mankind’s diversification into nations would be a consequence of the fall into sin, it would be a deviation from the path by which God wants humanity to develop.

In this case, the duty of all Christians would be to bring humanity out of this sinful state, to merge nations into a single one.

Is the diversification of mankind into nations a sin, or a consequence of sin? It would be enough to reject this supposition with the simple appeal to the universal law of gradual diversification of fauna and flora. It is not plausible that this law is contrary to God’s will, especially since these diversifications most often manifest an ennoblement of the basic trunk, not its degradation. But the answer can also be given differently: Sin or evil is of a different order than unity or diversity. It means distortion, disfigurement of the given thing, of existence produced by other powers. Is national specificity a distortion of the human, a fall from human being? It would be, when this national specificity would present itself as something vicious, petty, without heights and purities of feeling and thought. Yet who doesn’t know that there is nothing base in the specific way a member of a certain nation perceives and reacts in the world? In the feeling of the Romanian doina3 and in our hora4 I don’t believe there is anything sinful, or if there is something of that kind, it is not of national character, but human. The nation in the phase of sin has sinful manifestations, because human nature in general, with all the diversifications in which it presents itself, is sinful. Bringing people out of the sinful state is not done through the annulment of national qualities, but through the correction of human nature in general. If there were something sinful in national specificity itself, then no distinction could be made between good and evil within a nation, for all would be evil.

The question seems so evident to me that I consider it superfluous to insist further.

The knotty and challenging problem arises of the relationship between the national and the human. Does the national not obscure the human, not exterminate it? And if the human remains, isn’t the national perhaps a simple illusion, something superficial, which you can cast off at any moment you wish?

It should first be noted that there exists no a-national person. Not even Adam was a-national, but spoke a language, had a certain mentality, a certain psychic and bodily construction. A pure human, uncolored from the national point of view, without national determinants, is an abstraction. Just as there cannot exist an apple without the determinants of a certain variety, just as there cannot exist a human without individual determinants.

The human exists only in national form, nationally colored, just as it exists only determinately individual. One cannot extract from an individual or from a nation the individual or national determinants to leave the pure human. It would mean destroying the human itself. The national or individual is the human itself, which has, necessarily, a certain quality. A human without quality does not exist. The individual or member of a nation is human, is understanding of other people, of other nations, not through a surpassing of their individual or national quality, through a descent somewhere into the pure human substratum of their personality, but in the state in which they are. When a Romanian feels pity toward a Hungarian, in his pity he is still Romanian; the feeling of human brotherhood which he feels binds him to a Hungarian is a Romanian-colored feeling, not a-national.

What to our understanding appears antinomic, in fight one with the other, the human and the national, or, in other words, the identity between people and the difference between nations, in reality are inseparably united, in the most intimate and mysterious way, with the full maintenance of both; only a simplistic mind disregards one or the other of the terms of the antinomy.

From this follows that harmony between nations is not excluded, but very possible, for they are the same humanity standing in different forms, necessarily determined, here in one way, there in another.

Nations are, according to their content, eternal in God. God wants them all. In each He shows a nuance of His infinite spirituality. Shall we suppress them, wanting to rectify God’s eternal work and thought? Let it not be! Rather we will hold to the existence of each nation, protesting when one wants to oppress or suppress another and preaching their harmony, for complete harmony exists also in the world of divine ideas.

Vladimir Nikolaevich Ilyin, Saint Seraphim of Sarov, YMCA Press, Paris, 1930, p. 49 [in Russian]. Available here.

Sergius Bulgakov, The Lamb of God, Paris: YMCA Press, 1933, p. 149 [in Russian]. English translation by Boris Jakim. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2008.

Doina is a traditional Romanian lyrical song form expressing deep feelings like longing (dor), melancholy, or love. It has a free rhythm and often features melodic ornamentation.

Hora is a traditional Romanian circle dance where participants hold hands and move in a circular pattern, common at celebrations and community gatherings.