Dualism

Evgueny Lampert

Lampert, Evgueny. The Divine Realm: Towards a Theology of the Sacraments. London: Faber and Faber, 1944, pp 13-16.

The opposite pole to monism in the understanding of the world is dualism. God and the world remain divided, mutually exclusive and opposed to each other. Dualism admits the idea of creation. But it assumes ultimately not one but two creators, a “good” one and an “evil” one. The assumption of a second creative principle has its roots in the moral consciousness of man, in the search for a “justification” of God in the world, and springs from the need to explain the world’s evil and imperfections. Dualism occurs in the most varied and unexpected forms, especially where the intensity of religious experience confronts man with a dilemma, with a decisive “either... or” (Kierkegaard): God or the world. But it is also prompted by metaphysical motives.

The world, it is believed, though rooted in God as its Creator, cannot be without, as it were, a point d’appui outside God, or beside Him. This point d’appui establishes a basis of its own for the being of the world ad extra. God is conceived as wholly self-sufficient and, as it were, self-limited in being by His own divinity. The world in its distinct, specific nature finds no place or justification in Him. It remains for the world to seek ποῦ στῶ, an ontological place for itself “outside” the Godhead or “beside” it. Hence appears the postulate of a certain divine other-being, a second god who belongs entirely to this world. This second godhead is conceived either in various mythological images, as primeval matter, “Tiamat,” or in the form of a dualistic teaching about two gods, two divine principles not only distinct, but in a sense even opposite and struggling between themselves, although complementary: Ormuzd and Ahriman in the Iranian religions, and various forms of Gnostic doctrines.

It is easy to discern the utter religious absurdity of dualism, which is like pantheism only a veiled form of atheism: two gods are not Gods, for they are mutually exclusive. The reality of God implies His absolute character, and thus His uniqueness. If there has to be a “second” god beside the “first,” it follows that the “first” is no longer God. The idea of a double god (which, evidently, has nothing in common with the Christian revelation of the divine Trinity) is an expression of impotent thought lost in darkness and compelled to seek an issue in absurdity.

Even polytheism or heno-polytheism (Olympus) appears to be more consistent from the religious point of view than dualism, which provides no solution to its own problem. In polytheism we perceive the idea of a manifold divine world, which in its fulness, nevertheless, merges into a certain unity, into the divine “pleroma.” Its fundamental error lies in a false hypostatization of the rays of this “pleroma.” Dualistic atheism, on the other hand, is ultimately an obsession by demonism, in which the Prince of this world claims a place beside God.

This second principle in dualism, however, can be understood merely as a “place” for the world, ἐκμαγεῖον or χώρα of Plato, where the world is believed to find an existence for itself outside the absolute realm of divine life. The world cannot turn into sheer nothing in the face of this divine absolutism, and seeks its “something.” And it claims to find this in some kind of anti-god, “minus-god” — in God’s opposite. Yet minus is but minus, and remains so. If it is to change its “no-thing” into “some-thing,” it must needs receive the latter from the fulness of divine life and share in it. Or else it tries to absorb divine being in itself, to usurp it and thus oppose itself to God: thence the powerless convulsions of Prometheus straining and rending himself in demonic self-assertion. Yet divine being is indivisible and cannot be a part of itself. The attempt to take, to possess a part of it, that is, the attempt of dualism destroys itself, is ontological nonsense, which need not even be taken into account in the discussion of the general problem of the world. For either there is only God and nothing is beside or apart from Him; or there is only the world and nothing beyond or outside it.

In the face of this alternative the aspiration to find a place of its own for the world, to define its own being as distinct from the fulness of divine life is, nevertheless, perfectly legitimate and even inevitable. We must overcome the pantheistic nightmare which threatens us on the path not only of cosmism but of theism as well. The world must find its own place, so that it may face and even confront God: we must ontologically distinguish God and the world.

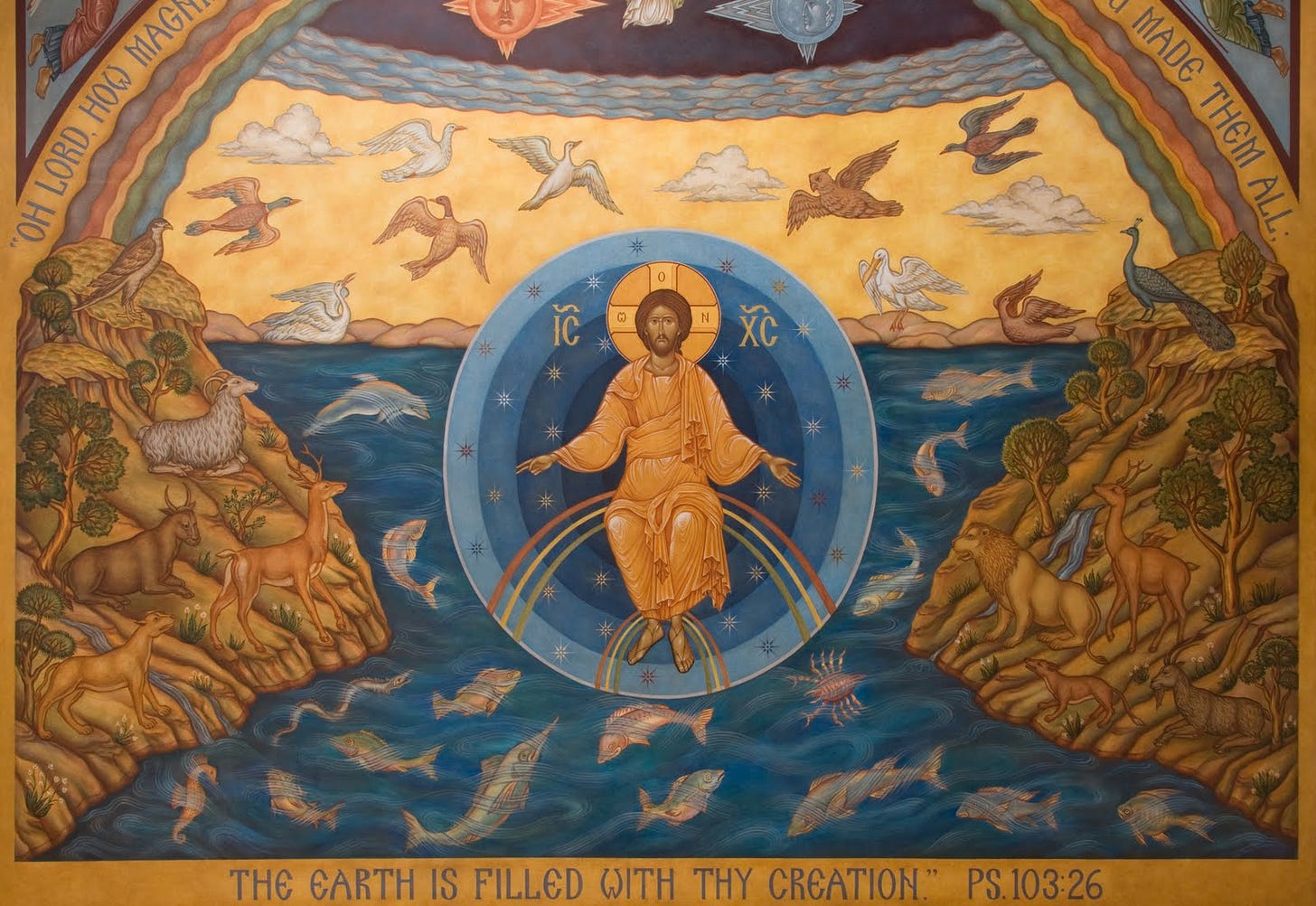

Even so the conclusion drawn from the impossibility of dualism will remain a negative one: there is not and cannot be any independent foundation for the world: And even if this exists, it must be established by God; for there is nothing which can be outside God or apart from Him, and hence be not-God or anti-God. This precisely is the idea expressed in the theological proposition, that the world is created by God, and, moreover, created “out of nothing.” Evidently this “nothing” cannot be understood as any kind of “something,” which might have existed “before” the creation of the world as some sort of material, or even as a “possibility” for the existence of the world. To understand “nothing” as any kind of “something,” veiled in whatever kind of metaphysical mist, as μὴ ὄν, or else as pre-existent “freedom” or “Ungrund” (Jacob Böhme, N. Berdyaev) is to open the door to dualism with all its disastrous contradictions. The “nothing” out of which the world is created is just “no-thing,” pure no, ontological void. In other words, the above proposition has primarily a negative significance: there is no foundation for the world outside God. “Thou hidest Thy face, they are troubled: Thou takest away their breath, they die and return to the dust. Thou sendest forth Thy Spirit, they are created: and Thou renewest the face of the earth” (Ps. 104:29-30).

If dualism is overcome consistently, are we not threatened with a certain divine monism, which is simply a counterpart and converse of atheistic or cosmic monism? If in the latter it is proclaimed that all is the world, and nothing is outside or beyond it, in the former we are facing the antithesis, namely, that all is God, and only God, that there is no place for any being outside God or beside Him; and, consequently, there is not and cannot be a world. In the history of thought this conclusion is precisely the usual attitude of mystically coloured pantheism: all is Atman, the breath of the Divine, Divinity. It seems, there is no intellectual issue out of this dilemma. This can indeed only be found by taking the whole question on to another level (μεταβᾴσις εἰς ἄλλο γένος), from the static to the dynamic, from the abstract to the concrete. The world is related to God not as His objectivized equal, as a form of being of its own co-ordinated with Him, but as His living self-revelation, as His “other-one” (θάτερον). It is created by God, it is God’s creation. Its existence is a witness to the divine-human, theandric nature of divine being. And for the world there is no other foundation or “place” of being than its createdness by God. The world is created out of the void; and this means that it exists in God, and only in Him, and has no foundation of its own. In itself the world is as it were without foundation, hung over the abyss, and this abyss is “nothingness.” The knowledge of “nothingness” is one of the deepest intuitions of the creature about its creaturehood. Thou art created — this means: all is given to thee, even thou thyself; to thee belongs, from thee proceeds only this abyss, this groundless chasm, gently and carefully veiled by the flowers of being.1

The world is created. Instead of being concerned with the question of a special place of its own for the world, of a second god or other-god, who in fact does not exist, there arises the whole problem of creation, by which is defined both the being of the world itself and its relation to God, for createdness is precisely this relation. The nature and character of this relation must be fully realized. But it is above all an object of faith, and the content of divine revelation. The truth about the world lies beyond its own limits and belongs to God. It cannot be established by the power of the human intellect, which bears the limitations of this world. Here lies the limit of human thought. Yet man can and must be aware of this truth in as much as it faces the world and is revealed in it.

It is of primary importance to realize the idea of creation in all its essential features, both in its positive and negative implications. We therefore again are faced with the general and preliminary question: is the world created by God, or has it its own independent, self-sufficient being?

For a further development of these ideas see below.