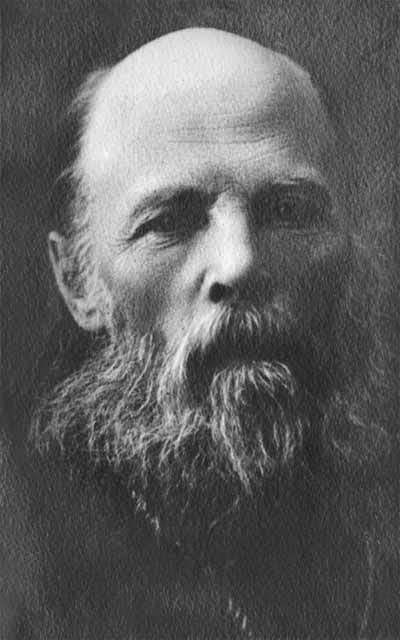

Father Alexei Mechev: Memoirs (Part Four)

N.A. Struve

Translated from

ОТЕЦ АЛЕКСЕЙ МЕЧЕВ: Воспоминания, Письма, Проповеди.

Редакция, примечания и предисловие Н. А. Струве.

YMCA-PRESS, ПАРИЖ. 1970.

Part One: https://www.chansonetoiles.com/p/father-alexei-mechev-memoirs-part

Part Two: https://www.chansonetoiles.com/p/father-alexei-mechev-memoirs-part-fa4

Part Three: https://www.chansonetoiles.com/p/father-alexei-mechev-memoirs-part-605

From the Recollections of Bishop Arseny1

Translator’s note: St Arseny [Zhadanovsky], born Alexander Ivanovich Zhadanovsky on March 6, 1874, in Pisarevka, Kharkov Province, was a prominent Russian Orthodox bishop and martyr. He hailed from a clerical family; his father, Protopriest John Zhadanovsky, and his brothers served in the clergy. In 1884, Alexander entered the Kharkov Theological Seminary, where Archbishop Ambrose of Kharkov prophesied his future as a bishop. After graduating in 1894, he taught at various theological schools. Seeking guidance on his spiritual path, he corresponded with St. John of Kronstadt, who blessed him to pursue monasticism. On July 17, 1899, he was tonsured as a monk with the name Arseniy in the Svyatogorsk Dormition Monastery. He was ordained a hierodeacon on August 14, 1899, and entered the Moscow Theological Academy the same year. After his ordination as a hieromonk in 1902, he graduated in 1903 with a thesis on St. Macarius of Egypt. He served as treasurer and later abbot of the Chudov Monastery in Moscow, where he implemented reforms to strengthen monastic discipline and spiritual life. In 1914, he was consecrated Bishop of Serpukhov, serving as a vicar in the Moscow Diocese. Following the Bolshevik Revolution, he faced persecution. He was arrested multiple times for his steadfast faith. On April 14, 1937, he was arrested again and accused of leading a counter-revolutionary organization. He was executed on September 27, 1937, at the Butovo firing range near Moscow. He was glorified with the New Martyrs and is commemorated by the Church on September 14/27.

Yes, Father Alexei was, one could say, filled with love. He did not know the harsh, cruel word “punish,” but knew only the merciful word “forgive.” He did not impose heavy and burdensome loads on his spiritual children; he was an enemy of any coercion, never demanding special feats from anyone; he understood that nothing needs compulsion when the leaven of the Holy Spirit is at work, when one ceaselessly seeks truth and righteousness, and when one is filled with the knowledge of Christ’s Divine teaching.

Proceeding from that same love, Fr. Alexei believed that there are no sins that “overcome” Divine mercy, and therefore he instilled in the souls of all who came to him a feeling of infinite hope in God’s mercy, no matter how heavy their moral and mental burden might be.

Toward those weak and still unsteady in spirit, he showed even greater tenderness, as if fearing to push them away through inattention or strictness, to disappoint them. Fr. Alexei did not ask those who came to him who they were, whether they attended church, whether they were believers, Orthodox or Catholic or of any other religion. For him, everyone who came was a “suffering brother and friend” seeking relief from their grief. He never left anyone without warm involvement, understanding with his loving heart that everyone’s pain is heavy to them.

And remarkably, everyone who came to Fr. Alexei had the feeling that the priest loved him more than anyone else. No matter how many times this was mentioned, the conviction remained: “Perhaps this comes from the fact that to each person Fr. Alexei gives some maximum of love,” said one of his spiritual children. Like the Heavenly Father, he made no distinction between those who came at the first or the eleventh hour: “You have come to me,” the priest would comfort them, “and so I give you all the love you can receive from me.”

Another of his spiritual sons reflected on the same topic: “Father Alexei showed each person a special loving relationship that set them apart from the general crowd and created the feeling that the priest loved him more than others.”

Merciful love — this is what made Fr. Alexei rich; this is why so many people left him spiritually healed; this is why the priest often brought those to the path of salvation who, finding themselves in life’s whirlpool, considered themselves lost; who despaired, no longer dared to go to an ordinary priest, but sought someone outstanding, special — and they found this special quality in Fr. Alexei.

Thus, Fr. Alexei was entirely aflame with love. If he did not speak of love, then his gaze and every movement testified to it. Through his relationship with people, he preached what we read in the moving words of St. John Chrysostom at Pascha, where this invitation is made: “Come all to the great Feast of the Resurrection of Christ — both those who have fasted and those who have not, those who came early and at the last hour — come all, doubting nothing. On this day the doors of Divine love are open to all.”

Furthermore, Fr. Alexei possessed sound judgment and penetrating intelligence, which gave him the opportunity to develop in himself great spiritual experience that, combined with his constant vigilance over himself, manifested in his ability to heal the spiritual wounds of others. Fr. Alexei wordlessly understood the feelings of all who came to him as their spiritual father; he knew human weaknesses well and, without indulging them, would somehow especially carefully, delicately, and tenderly touch each person’s soul. He never showed that he was surprised by anyone’s sins, did not rebuke the sinner, but tried imperceptibly to bring him to an awareness of his guilt and repentance, presenting before him living examples of human errors and delusions, from which the person who came had to draw an instructive lesson for himself.

Fr. Alexei’s ability to reach the depths of a person’s soul was further aided by his perspicacity, based on that same spiritual experience. When he began to talk with his visitor, the latter felt as if he were in a state of spiritual “X-ray” (in the expression of one of the priest’s spiritual children). He noticed that all his inner life, with its mistakes, sins, and perhaps crimes, was known completely to Fr. Alexei, that his gaze somehow physically saw everything, not only what was reflected in external events and your actions, but even what emerged from the depths of thoughts and experiences. It was completely useless to hide from this all-seeing pastor: his very first questions and first answers showed the visitor that it was better to stay silent about oneself. Moreover, Fr. Alexei not only understood and saw another’s life but was able to find its solution, often unknown even to the person who had come to see him.

Fr. Alexei knew how to speak not only about the symptoms of spiritual ailments and their deep causes but also to indicate radical means for their cure. He was an experienced spiritual physician who had studied spiritual medicine to perfection, and just as earthly doctors have their methods of treatment, so too Fr. Alexei had his starting points for healing spiritual ailments.

First of all, he demanded repentance, not formal but deep, sincere, tearful, capable of producing a rebirth and renewal of the sinner’s entire inner nature. For this reason, Fr. Alexei did not like confessions from written notes, but required a conscious attitude toward one’s actions and a firm intention to improve. “Always consider yourself guilty,” he said, “and justify others.”

For the priest, according to the word of the Apostle Paul, repentance meant putting off the old man and becoming a new creature (Eph 4:22-24 and Col 3:9-10). And since such repentance is often hindered by our weak, flabby will, paralyzed by bad habits and passions, everyone who wishes to lead a life in Christ must, in Fr. Alexei's opinion, pay attention to strengthening this will.

The priest himself, as an experienced pastor, offered his spiritual children many different means of spiritual healing, conforming to the spiritual makeup of each person: to one he would advise submitting to God’s will in everything, seeing therein the most blessed providence of the Creator; another he would urge to attend God’s temple more frequently, saying: only in church, in an atmosphere of love, will your heart warm up and thaw; to a third he recommended monthly confession and communion of the Holy Mysteries; to a fourth he assigned work at the temple — to sing, read and serve — drawing all of them to faith in the Lord while simultaneously correcting them with his tenderness and love.

Besides his ability to heal souls, Fr. Alexei was distinguished by an extraordinary observation of everything around him, of all external life both urban and rural, peasant and worker, and could boldly tell an inquirer whether or not he should open a business, start a family, leave his homeland, build a house, etc. In this regard, he was a wise elder, found not in a monastery but in the very thick of human society. Fr. Alexei was an urban elder, bringing people no less benefit than any desert dweller. In the form of a pastor, he was one of those ascetics about whom St. Anthony the Great prophesied, saying that the time would come when monks, living among cities and worldly vanity, would themselves be saved and lead others to God.

Moreover, Fr. Alexei was an “elder above elders,” “a guide for spiritual fathers.” He often had to smooth out improper relations between spiritual fathers and their children. This matter, according to the priest, was difficult and delicate; however, he always conducted it successfully. Fr. Alexei did not do what many elders do, using their authority: he did not cancel or change the guidance of spiritual fathers, thereby sowing confusion in the souls of their children, but knew how to act in relation to both in perfect harmony.

Our characterization of Fr. Alexei’s personality apparently does not agree with the widespread opinion that he was opposed to monasticism and did not advise his spiritual children to accept it. However, one needs to know to whom and under what circumstances he did not advise it. Being a spiritual pastor, Fr. Alexei could not help but value monasticism in its ideal and true foundations; he only disapproved of those who accepted it out of vanity, without understanding the meaning and significance of such a great calling. “Monks living in the world cannot fulfill those external rules by which they are bound by their position.” And this could happen precisely with members of the Maroseyka spiritual community, working in the world and, nevertheless, striving sometimes to receive monastic clothing and fasting out of self-will, without the blessing and guidance of their priest. Fr. Alexei had another reason not to let go of his spiritual children, even to monasteries: he concentrated all his pastoral work on the households of the bustling capital, aiming to bring them to salvation; and so, keeping with him many fervent members, he wanted to strengthen the community through this, to influence it morally, while at the same time giving these same people work in the place where the priest thought to make them useful to Moscow, which needed spiritual enlightenment.

That Fr. Alexei was not in principle against monasticism is testified to, besides by his friendship with the Optina elders, by an interesting letter from the priest, received by me, the writer of these memoirs, not long before his death. In it, while prayerfully greeting me on the occasion of my recovery from illness (inflammation of the lungs) and expressing a desire to see me again soon or later in Moscow, in the Chudov Monastery, together with all my flock, he among other things makes this request: “Then accept your humble servant under your protection too. I want to spend the last days of my life under the shadow of St. Alexis’ monastery.”

However surprising it may be, Fr. Alexei’s pastoral activity especially developed and strengthened when religious interests declined in society. And it must be said, the priest’s work proved very beneficial. One of the visitors to the Maroseyka church relates the following:

“Soon after those days memorable to us all, a new epoch began, which seemed especially difficult for those who were not drawn to the new order of things; at that difficult time, people wanted to go somewhere far away to hear warmer words and live with different, good feelings of love and peace, and not with the malice and hostility that were spilling out everywhere. And so, in this period of general ‘anger’ and irritation, it was a joy to visit the small, modest church of St. Nicholas on Maroseyka, which breathed with grace-filled atmosphere, to listen to the service and artless sermons of Fr. Alexei, flowing from the depths of his soul; to heed the constant fervent call of the priest to active love, meekness, forgiveness of offenses, and noting his persistent indication that salvation is possible in any situation — everything coarse and materialistic happening outside the walls of the church was completely forgotten, and everyone wanted then to forgive all, to pray for all...”

Looking at Father Alexei’s face, which radiated an ineffable quiet joy, everyone felt their spirits lift and sensed they were experiencing something kind and uplifting that made them look at life with different eyes — and feel pity for the world, which was mired exclusively in earthly calculations and unwilling to know any higher order. The “spirit of despondency” that usually accompanied those who came to pray at the temple at that time would disappear without a trace, and they would return home calmed, with a bright feeling of hope for something better.

One cannot forget those moments when, after the all-night vigil, Father Alexei would begin singing “Beneath Thy Protection” in a voice full of vigor — and the whole church, as one person, would join him. During these times, everyone was filled with firm hope that the Most Holy Mother of God would not despise the prayers of singers in distress and would send Her mercy. Everyone would leave the temple then full of confidence that they would calmly survive the coming night, even if troubled with all sorts of misfortunes.

An even stronger impression was made by the night prayers occasionally held there on Maroseyka Street. They seemed to suggest to everyone: “We are Christians, awaiting the glorious coming of the Lord, and we should fear no one and nothing. There is nothing good to expect from life, so let us gather here to prayerfully meet our sweetest Savior.”

Thus invisibly Father Alexei pacified the passions that were strongly raging in our time, saving many from despair and turning others toward the path of repentance.

There were cases when people with evil intentions would come to him in the temple, but sensing the blessed atmosphere there, they would stay, transform, change for the better, be reborn and even become members of the Maroseyka church brotherhood. Father Alexei’s service to contemporary society in calming and pacifying hostile and troubled hearts is great, though few understand and value this...

It was pleasant to see and converse with Father. Besides meeting him at gatherings of the pastoral brotherhood in memory of Father John of Kronstadt, I had the consolation of praying in his temple. I recall a solemn evening organized here for children by the “Chrysostom” study circle. An extraordinary number of children gathered, and an incredible spiritual atmosphere filled the church. The organizer of such a rare service, perspiring profusely, made every effort to give the children spiritual instruction that would leave a lasting impression on their hearts. I cannot forget the kindness and welcome shown to me then by Father.

Father Alexei provided great moral support to my Chudov spiritual children, who were left without a guide due to the circumstances of the time, and to the holy monastery where they had prayed and found consolation.

One of our spiritual daughters related the following to us about this:

“When we were deprived of the Chudov Monastery, and like sheep without a shepherd were scattered everywhere, not knowing where to lay our heads, many of us went to Maroseyka to Father Alexei, and the kind Father with extraordinary love and tenderness took us sorrowful, sad orphans under his care, saying for our consolation: ‘The Lord has blessed you to me — we are of one spirit. Come to our temple, and I will not abandon you.’”

And Father Alexei did much for the Chudov people; if a prayer service was needed, he always went himself to serve it; if someone wanted counsel, he never refused, and would even say: “Come to me at any time.” If someone fell ill, he would immediately rush to visit and comfort them with such words: “I came to church, learned you were sick, and hurried to you so you wouldn’t get worse. Get well soon, we shoulldn’t both be sick, as they’re waiting for us at the temple.”

After the lengthy monastery services, it was very difficult for the Chudov people to adapt to parish services. I remember Father would remind me: “Look here, don’t forget to come to church in the evening.” And I would reply: “I cannot come to you, I don’t like either the reading or the singing there, everything is done hastily, not like at our Chudov.” It should be noted, however, that Father Alexei himself was terribly burdened by this haste, the theatrical singing, and the irreverent service of his deacon; yet he endured it all, as he would say, only out of necessity.

And so one day he addressed the church with this proposal: “I will dismiss the hired singers, whom I simply cannot stand anymore, and all of you present here shall sing and read. You, Maria, be the canonarch, for you pronounce the stichera well and clearly. I hope, with God’s help, you will manage the church service. May the Lord bless you to begin and fulfill this work.” And indeed, through the prayers of St. Alexis and the efforts of Father, gradually a proper order of services was established at Maroseyka. At first, truthfully, both we and Father Alexei had to endure quite a few reproaches from worshippers who grumbled about the lengthy services. Sometimes one of them would say: “Father, many are dissatisfied that the all-night vigil is dragging on.” And he would smile and answer: “Never mind, don’t be troubled, later they will all be grateful and find consolation.” And so it turned out. Which of the believing Muscovites now doesn’t know Maroseyka for its spiritually uplifting services and church order? And it is consoling to me that partly the influence of our dear unforgettable Chudov Monastery, for which Father had great reverence, was manifested here.

It would happen on a feast day that one would ask him: “How do you bless us to conduct the service?”

“And how was it done at your Chudov Monastery?”

“At Chudov it was done such-and-such a way.”

“Well then, do it the same way; after all, we now also have Chudov Monastery here,” Father would say with a smile, all beaming.

Sometimes he would even himself suggest doing everything according to Chudov customs. Here, for example, I have kept such an instruction written in his hand: “Maria, sing the akathist for the feast of the Kazan Mother of God with chanting, as in Chudov Monastery.” When Saint Alexis’ feast day would come, he would immediately enliven the vigil service, and have the akathist sung, and after the liturgy serve a solemn moleben. How much Father valued the work of the Chudov sisters is evident from his often repeated words: “Thanks to the Chudov sisters, we have established a monastic service.” Such love of Fr. Alexei united us all into one family and brought joy, which increased even more because Father deeply respected and tenderly loved our spiritual father — Vladyka Arseny. Whether it was Vladyka’s Angel Day2 or some other memorable event from the latter’s life, Fr. Alexei would commemorate both the departed parents of the bishop — Archpriest John and Theodosia.

It is difficult and sad to describe the final days and death of spiritual friends who brought you much joy and consolation. But we must do this regarding the ever-memorable Fr. Alexei.

From increased pastoral labors and life’s hardships, he began occasionally falling ill: his heart started troubling him, and then he had to receive visitors while lying in bed, and to this was added the infirmity of his old age. This last circumstance, having interrupted communion with his spiritual children, deprived Fr. Alexei of the necessary fresh air, as it were, and made him feel that in connection with the current ecclesiastical situation his poor health no longer held him back and did not cause inner reproach. He saw as he “lay in the vale of tears” heavenly habitations where there is “neither sorrow nor sighing.”

Fr. Alexei worked tirelessly and benevolently in Christ’s vineyard. Now he has died and only memories of him remain. As in earlier times, the Lord takes good, holy pastors. Here one must see God’s punishment of us for our sins.

“I will destroy your altars, I will take away your priests,” Jehovah spoke through the prophet Jeremiah to the Israelites when they became corrupt and unworthy bearers of true faith in God.

Fr. Alexei foresaw his end in advance: thus, first of all, he began to talk about it and gradually transfer care over the flock and church force to Fr. Sergei,3 who was already helping him in the temple. Two months before his death he said to one of his spiritual daughters: “Maria, I must set you an example and send you to confession to Father Sergei, for he must remain as my replacement.”

However painful it was for Maria, who was accustomed to the blessed Fr. Alexei, she went in obedience. Soon after this, when meeting her, Father asked:

“Well, did you go to Fr. Sergei? And are the sisters going to him?”

“Yes, Father, I went,” answered Maria, “and others are gradually getting used to him.”

“Well, now I can die peacefully,” said Father, “he will be a good pastor, better than me.”

Thus Fr. Alexei, not long before his death, transferred his spiritual children to Fr. Sergei and wiped away a tear.

Usually in summertime he would go to rest in Vereya, to his dacha. It was planned in 1923 to send him there, but this time everything happened somehow in a special way.

First of all, Father gathered himself unexpectedly, hastily, and his farewell was somehow mysterious. After serving the Divine Liturgy, he gave everyone Holy Communion and blessed each with an icon of St. Nicholas, saying: “I bless you with our master” — that’s what he called the saint, the patron of the Maroseyka church — “I feel very unwell, I’m leaving, but will return soon.”

Indeed, only nine days had passed when a telegram was received announcing Father’s sudden death. He died on June 9, 1923.

It was clear that Father had deliberately gone to Vereya to die, intending, among other things, to complete his final testament there in freedom. All those around him noticed how he rushed to write it, refusing his usual walks in the sun. When they called him from his room to go outside, he would say:

“No, I’ll write it here in the quiet, my thoughts scatter out there, I won’t be able to finish.” And he would add: “After all, I came here to work on it; in Moscow they wouldn’t let me.”

In his final days, Father behaved as if something had happened to him, or as if he was waiting for something: he spoke quietly, moved slowly, as though afraid to disturb his inner world, and seemed somehow inwardly illuminated. On his last evening, he was cheerful and especially affectionate with everyone. Fr. Alexei died suddenly from heart failure.

The unexpected death of dear Father struck everyone like thunder. The body of the deceased, on the eve of burial, was brought from Vereya to Moscow around 6 o’clock in the evening. The coffin was met by the clergy, relatives, sisters and brothers of the Maroseyka community, and a huge crowd of people that could not fit into the small church of St. Nicholas.

To allow everyone to pray, two all-night vigil services were held: in the church by His Grace Herman, Bishop of Volokolamsk, and in the courtyard by Tikhon, Metropolitan of the Urals. The service ended around midnight. Throughout the time between services, a panikhida was served. At 10 AM, the liturgy began, celebrated by Bishop Theodore, the abbot of Danilov Monastery, with 30 priests and 6 deacons concelebrating, and about 80 clergy singing. There, Father Alexei’s final testament was read to the spiritual children, and several funeral orations were delivered. At 5 o’clock, during the singing of Paschal hymns, the funeral procession moved to the Lazarevo cemetery, where Patriarch Tikhon, who had been released from confinement several hours earlier, arrived to meet it.

His Holiness refused to enter the church, which had become renovationist4 in his absence, and vested outside in the open air. Here, in this way, a public condemnation of the main renovationist church took place, a condemnation as immediate as was possible to make.

“Before resurrection, one must die,” and Fr. Alexei died so that joy might be given to the Church.

As soon as the coffin was brought through the church gates, thousands of people showered His Holiness and the deceased with fresh flowers. A bee instinctively flies to where there is honey, and truly Orthodox people, through their spiritual intuition, recognize where God’s mercy will be manifested, as happened at Father’s burial at the Lazarev cemetery.

His Holiness served the funeral liturgy, lowered the coffin into the grave, and was the first to throw earth upon it. Then the Primate of the Russian Church began blessing the people, which continued for several hours. During this time, they managed to build the grave mound, erect the cross, arrange all the wreaths in order, and serve a full panikhida, which was celebrated by the deceased’s son, Fr. Sergei. The day had completely turned to evening; it was nine o’clock when everyone dispersed to their homes, leaving dear Father at his new place of residence, no longer among the living but among the dead. But while many people die both physically and spiritually, Fr. Alexei died only physically –- spiritually he remained with us, as evidenced by his living memory and the unceasing prayers of his spiritual children.

And we believe that the path to his grave will not become overgrown, just as paths to holy ascetics and elders in Russia never became overgrown.

For greater completeness of our account, let us cite several testimonials about the deceased Fr. Alexei Mechev from his admirers.

“The image of Fr. Alexei left an indelible impression on us,” says one of them. “One cannot forget his eyes that shone with an otherworldly light, their penetrating glance, nor his purely Russian, dear, blessed, gently smiling face, on which was written such goodness and spiritual warmth that it seemed there was enough of it in abundance for all who had the happiness to see and meet him.

“We still hear Fr. Alexei’s voice, not strong, but pure, which rang with a particularly appealing tenderness. From the very first meeting with this welcoming shepherd, everyone felt confident that they could approach him fearlessly with any grief, with any moral burden, that here was a person who not only would not repel with indifference, but would give you everything you needed. I experienced this myself.

“After a great family sorrow — the loss of a close relative — I hurried to Maroseyka. With his sensitive heart, Fr. Alexei understood the depth of my grief and comforted me without any words, simply by his gracious presence. After the panikhida, in a burst of gratitude, I involuntarily exclaimed: ‘Dear batyushka!’5 Yes, this title perfectly characterized Fr. Alexei, as he was truly, in the fullest and best sense of the word, a ‘dear batyushka.’”

“When you remember Fr. Alexei,” says another of his admirers, “what comes to mind is not only him, but also that grace-filled moment that you experienced upon meeting him. Batyushka — this whole experience means that you were once sincerely pitied, embraced, loved, and even more: with batyushka you felt the Creator, drew closer to Him.

“This is how Fr. Alexei is perceived by us, as a step placed against our heart for drawing nearer to God Himself. And can one express in human speech the joy of communion? — And what joy batyushka gave us.

“Fr. Alexei appears before us during that period of life’s struggle when he had already managed to lay down everything of his own in the field of Godly obedience and self-denial. We saw him at the moment of victory over himself, when his face began to shine, and his light-blue eyes began to see the doors to Christ’s dwelling as already open for entrance. Here is joy for all of us, his spiritual children.

“Batyushka Fr. Alexei belongs to those Russian righteous ones whose lineage begins from St. Seraphim of Sarov, continues through Optina Desert and reaches our days. This is the type of elders illuminated by the quiet light of humble love for all who suffer. Such righteous ones are precisely what is needed by people who are weary, tormented by life’s sorrows, afraid of any careless touch to their wounds; the latter cannot be immediately forced to break with the life they lead; such an attempt can only finally torture and generate despair. They need exactly the humbly merciful ‘Seraphims,’ like Ambrose and all the Optina spiritual fathers were, radiating love and tenderness around themselves. Such also was Fr. Alexei for us — the same merciful love, the same tenderness in his gaze and joyful smile on his lips, the same heartfelt welcoming manner.

“In the fellowship of these holy fathers mentioned above, many were spiritually reborn and came out from there as from a baptismal font, and from communion with Fr. Alexei, harsh and sinful souls were softened and would leave him in purifying and grace-filled tears...

“Thus batyushka Fr. Alexei was a healer like St Seraphim for those who suffer. He came to us already weak in body but strong in love and desire; he walked with us at that moment when we all especially needed consolation; he walked, and very soon reached the grave, to our great sorrow. But he was there hidden only bodily; in spirit he arose to the heavenly Jerusalem, so that there he might meet us again on the difficult paths of otherworldly trials and, with the same love, compassion, and tenderness, lead us to the throne of the Lord, paying for our sins with his own prayers.”

Batyushka, Father Alexei, eternal memory to you, dear one.

The Memoirs of Bishop Arseny are based on the manuscript of S. N. Durylin (published in Part Two of this series); therefore, to avoid repetition, they are printed with abridgements.

Translator’s note: In Russia, Angel Day (День ангела) refers to a person’s name day — the day dedicated to the saint after whom they were named, who is considered their spiritual protector or “angel.” On one’s Angel Day, it is customary to honor the saint, attend church services, and celebrate with family and friends. This day is often viewed as more spiritually significant than a birthday, as it emphasizes one’s connection to the faith and their patron saint’s guidance throughout life.

Translator’s note: Sergei Mechev, born on September 17, 1892, in Moscow, was Fr Alexei’s son. He pursued higher education at Moscow University, initially studying medicine before transferring to the Faculty of History and Philology. During World War I, he served as a nurse on the front lines, where he met his future wife, Euphrosyne Shaforostova; they married in 1918. Influenced by his father and spiritual mentors, including Elder Anatoly of Optina, Sergius was ordained a priest in April 1919. He began his ministry at the Church of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker on Maroseyka Street in Moscow, serving alongside his father. After his father's death in 1923, Father Sergei assumed leadership of the parish, continuing its spiritual traditions and guiding the community through challenging times. Father Sergei was known for his deep pastoral care, emphasizing repentance and frequent participation in church services. He maintained a spirit of humility and sincerity, fostering a close-knit spiritual family within his parish. His commitment to the Orthodox faith led him to oppose the Renovationist movement (see note below), which sought to align the Church with Soviet policies. This opposition resulted in multiple arrests and periods of exile. In November 1929, Father Sergei was arrested and sentenced to three years of exile near Arkhangelsk. Despite these hardships, he remained in contact with his spiritual children, offering guidance through letters. After his release, he continued his pastoral work but faced further persecution. He was arrested again in March 1934 and sentenced to five years in labor camps. During World War II, he was arrested once more and is believed to have been executed in early November 1941. Father Sergei was glorified as a New Martyr by the Russian Orthodox Church in 2000, recognized for his unwavering faith and dedication to his flock amid persecution.

Translator’s note: The Renovationist Church, also known as the “Living Church” (Живая Церковь), was a schismatic movement within the Russian Orthodox Church that emerged in the early 1920s, during the Soviet period. It sought to align the Church with the goals of the Soviet state and promoted modernist reforms, including the relaxation of traditional Orthodox practices, married bishops, and a more democratic church governance. The movement gained state support as the Soviet government saw it as a way to weaken and control the Russian Orthodox Church. However, most clergy and laity rejected the Renovationist Church, viewing it as a betrayal of Orthodoxy. Over time, the movement lost influence, and by the late 1930s, it largely dissolved, with many of its clergy seeking reconciliation with the canonical Russian Orthodox Church.

Translator’s note: An endearing and respectful term for a Russian Orthodox priest, literally meaning “little father.”