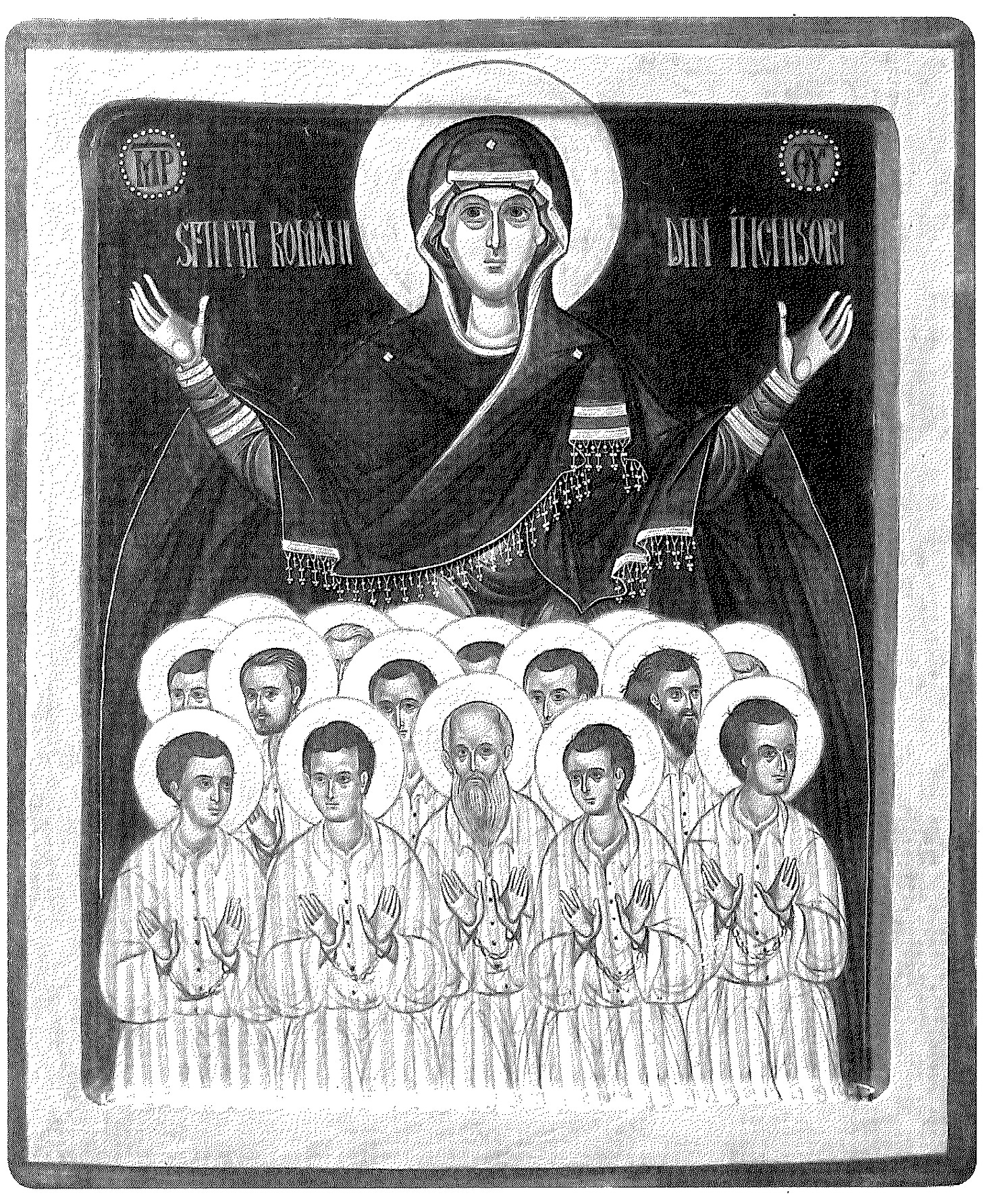

“Let Us Bring Their Holiness To Light”

Father Iustin Pârvu

Translated from Sfinții Închisorilor. Mănăstirea Paltin Petru-Vodă, 2019

Our country is a holy land, the land of the Mother of the Lord just as it is for the other Orthodox countries, but especially for us in these times, because here were born and grew up multitudes of young and old who stand as testimony to the truth against the red beast from the East: Aiud, Gherla, Pitești,1 where one can see their blessed bones — the grace of the Holy Spirit and a testimony of our righteousness in the Orthodox world.

In prison they were crushed and broken, both spiritually and physically, because because most of those arrested with minor sentences died, poor souls. These were quickly taken away. Meanwhile, others clung to life, struggling to survive no matter the cost. Solitude was the weapon of disintegration and the hardest trial. Yet, in this solitude, the Spirit of God began to work within them. It began to descend deeper into the soul, and prayer arose, which became the salvation of all. It was like the reading of the Psalter in a monastery, hour by hour. In the corner of the cell, the Akathist and the Paraklesis2 were recited from memory, without books.

Our salvation was closely linked to those who had been arrested during Antonescu’s time. They had memorized entire passages from the early volumes of the Philokalia. Even the desert saints had not been so immersed in such spiritual study.

In all times, there have been people who have preserved the spirit of prayer. In prison, we were deprived of Christian rights, but we gained the inner paradise. Confession and Communion happened at great peril. At Pascha and Christmas, Communion was taken starting from the second floor, then descending to the first, the ground floor, and the basement, and if you were caught with something in your bosom or pocket, you would face the most severe torture. Communion was prepared from bread, formed into a small lump the size of a pea, and carried past all the strict inspections. In those small pieces of bread was contained all gold, all wealth. Along with powerful prayers, there were also beautiful poems. Radu Gyr3 and others wrote poetry as a form of prayer. If spiritual life was preserved there, it was thanks to the poetry of Radu Gyr. And God granted that these men of great talent be brought to us, that through their holy remains, they might guide us and protect us through their prayers from the evils that are now, and those that are yet to come.

The lives of these martyrs are already known through their holiness, through their deeds, and through their entire conduct; they lived and still live among this people. At last, they have proven that from their very youth, they sacrificed themselves for this Orthodox truth. Now, for us, the most important thing is to draw as close as possible to their sacrifice so that we too may find boldness before God through them.

Our rulers in the land of Moldova once had no holy relics, no recognized saints, and no miracle-working icons. But they took action, and through their efforts, we received Saint Parascheva.4 In the same way, we came to possess miracle-working icons, before which the entire nation now bows in worship.

All these, in the end, were values brought from the Orthodox world, and our rulers believed that the more saints we had, the more zealously the country would be protected against invasions and historical hardships we have endured over time — relics and icons that have covered the land with prayer and with their presence.

And in this 20th century, which has borne these young men who took the path of the Cross, sacrificed themselves, and spent their youth wasting away in prison cells, it proves that the good God remains with Romanian Orthodoxy. At the same time, it is an exhortation for us today to follow their ascetic struggles and martyrdom. And if God has not blessed us to endure their sufferings, then at the very least, let us bring their holiness to light and venerate them as saints who pray for us. The more saints we have, both officially and unofficially, the more God’s mercy will be upon us, and we will find boldness before Him through our saints and martyrs.

All the peoples of Eastern Europe have gone through this Bolshevik oppression — the Bulgarians, the Serbs, the Czechoslovaks, the Poles, and the Hungarians: nations that also put up a strong resistance against atheism. But what has stood out especially in our case is that Romania had very wise youth, deeply imbued with the essence of this Orthodox truth, so that through their sacrifices, I believe, we far surpassed all the surrounding nations. This is why the primary target of punishment and persecution against Orthodoxy in the Balkans has been, and still is, our country — Orthodox Romania — with this generation of martyrs who, at last, took the bull by the horns against communism and against all the foreigners who had sold their conscience and their nation. But it is not enough to admire their labors and struggles; we must also experience them ourselves, in our own flesh, for this is how Orthodoxy has been forged to this day.

When the terrible arrests were carried out in our regional prisons, as in Suceava in 1949, children of 15 or 16 years old lay there, and even infants taken from nurseries and brought with their mothers for interrogation, while their fathers were imprisoned. What sacrifice could be more pleasing and pure than that of this generation, before whom we ought to bow in reverence?

The youth of 1948 — they were the elite of our nation; the rest… mere bystanders beside them.

To speak of a people’s martyrs, one must be well acquainted with suffering, so that the one who listens may recognize it in you. He will taste of your teaching, and of course, the bread made with tears and suffering will seem more flavorful than that of today’s merchants. Of course, it is difficult, especially when one first sets out on the path of the Cross. And I, when I first stepped onto this path, was at first disoriented and doubtful of my victory over suffering.

When I entered my cell in Aiud for the first time, my first thought was that this cell would be my grave. But things did not turn out that way at all. Here I found young men who had been condemned under Antonescu in 1940 and 1941, who had already endured several years of imprisonment. The strength of character and spiritual fortitude I found in these young men was so great that, for me, the cell became a tomb of resurrection, a place where the radiance of divine grace shone forth.

Translator’s note: Aiud, Gherla, and Pitești were notorious Romanian prisons used during the communist period. Pitești Prison is especially infamous for the “Pitești Experiment” (1949-1952), one of the most brutal “re-education” programs in the Eastern Bloc, where political prisoners (many of them students and intellectuals) were subjected to torture, not merely to force them to renounce their political and religious beliefs, but in a deliberate attempt to break and corrupt their inmost conscience. Fr Georges Calciu has borne particular witness to this “experiment.” Aiud and Gherla were also harsh prisons where many political prisoners, including intellectuals, clergymen, and former politicians who opposed the communist regime, were incarcerated and subjected to conditions of diabolical brutality.

Translator’s note: The Akathist is a hymn of praise and supplication, traditionally dedicated to Christ, the Theotokos (the Virgin Mary), or a particular saint, and is recited while standing, expressing deep devotion and perseverance in prayer. The Paraklesis (or “Supplicatory Canon”) is a service of intercession, most often addressed to the Theotokos, asking for her aid and protection in times of distress.

Translator’s note: Radu Gyr (1905–1975) was a Romanian poet, essayist, and journalist known for his nationalist and Orthodox Christian themes. A member of the Legionary Movement (Iron Guard), he was imprisoned both during and after World War II, suffering harsh persecution under the communist regime. His poem Ridică-te, Gheorghe, ridică-te, Ioane! led to a death sentence in 1959, later commuted to life imprisonment. His poetry, deeply spiritual and centered on suffering, martyrdom, and hope, became a source of resilience for political prisoners. While revered as a martyr of anti-communist resistance, he remains controversial due to his ties to the Iron Guard.

Translator’s note: Saint Parascheva of the Balkans (also known as Parascheva of Iași) was a 10th-century ascetic whose relics were highly revered in the Orthodox world. In 1641, Prince Vasile Lupu successfully arranged for her relics to be transferred from Constantinople to Iași, the capital of Moldova at the time. This was seen as a major spiritual acquisition, bringing Moldova closer to the Orthodox heartland and providing a powerful holy presence in the region.