Man and Earth (Part Two)

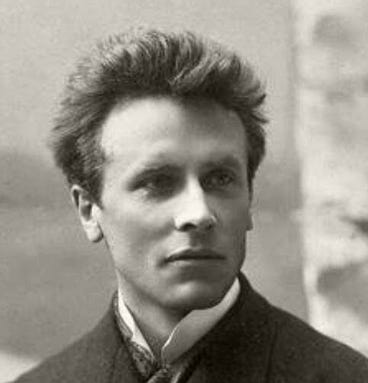

Ludwig Klages

Translated from Ludwig Klages, Mensch Und Erde

But how could there still be great individuals under such circumstances? We certainly do not deny the value of inventive genius in the masters of technology or of organizational talent in the magnates of large-scale industry; but even if one were to elevate such abilities to the same level as genuine creative power, it remains certain that they would never be capable of enriching life. The most ingenious machine has meaning only in the service of a purpose, not in and of itself, and the largest industrial conglomerate of today will be nothing in a thousand years, whereas the songs of Homer, the wisdom of Heraclitus, and the compositions of Beethoven remain part of life’s timeless treasure.

But how bleak is the state now of our intellectual and poetic achievements, which were once rightly celebrated! Whom do we have left, now that the luminaries of intellect and action in all fields have departed: Burckhardt, Böcklin, Bachofen, Mommsen, Bismarck, Keller — now that even Nietzsche, comparable to the last flare of an ancient fire, has vanished without a trace or successor? Empty is Mount Parnassus, empty are politics, empty is philosophy, not to mention the utterly decayed state of art.

And if we descend to the realm of everyday life, the catchphrases of “individuality” and “culture” reveal their complete emptiness.

Most people no longer live but merely exist — whether as slaves to their “profession,” mechanically consuming themselves in the service of large enterprises; as slaves to money, mindlessly surrendering to the numerical delirium of stocks and investments; or, finally, as slaves to the dizzying distractions of metropolitan life. Many others, however, dimly sense the collapse and the growing joylessness. Never before has dissatisfaction been greater or more poisonous. Groups and factions unite ruthlessly around narrow interests; in the relentless struggle for survival, industries, social classes, nations, races, and religions clash fiercely, and within each group, individuals driven by selfishness and ambition contend with one another.

And since humanity always interprets the world in the image of its own state, it believes it sees in nature a wild struggle for power, imagining itself justified when it alone survives the “struggle for existence.” Humanity envisions the world as a vast machine, where pistons must always pound and wheels must always spin — without ever asking to what end this “energy” is being converted. And with a verbose so-called monism, it manages to distort and degrade the infinite life of all celestial bodies into nothing more than the pedestal of the human ego.

Where once love was praised, or renunciation, or the God-intoxicated ecstasy of transcendence, today a kind of religion of success is practiced. On the grave of the ancient world, it proclaims that petty creed of which Nietzsche’s searing scorn had already forewarned when he made his “last man” say, with a blink of the eye: “We have invented happiness!”

The shallow errors of all these systems, sects, and movements will, of course, not endure for long. Nature knows no “struggle for existence,” only the struggle arising from care for life. Many insects die after mating, showing how little nature values preservation if only the wave of life continues to roll forward in similar forms. When one animal hunts and kills another, it is driven by hunger, not acquisitiveness, ambition, or lust for power. Here lies a chasm that no logic of evolution will ever bridge. Species have never been exterminated by other species; any excess on one side is quickly counterbalanced as prey becomes scarce and the predator’s food supply diminishes. Instead, species turnover has occurred over vast time spans due to global environmental processes, leading to a constant increase in life-forms.

The extermination of hundreds of species within a few human generations cannot be compared to the extinction of the dinosaurs or the mammoths. Entirely devoid of sense is the application of physical quantitative laws, such as the law of the conservation of energy, to questions of life. A living cell has yet to be created in a test tube, and if it were, it would not happen through the combination of “forces” but because even chemical substances already harbor life. Life is a form capable of persistent renewal; if we extinguish it by eradicating a species, the Earth is impoverished forever, regardless of the so-called conservation of energy.

Such false doctrines, as noted, will disappear, but not the consequences of the actual course of events, of which all theoretical constructs are merely the intellectual shadow. There is no basis for the belief that the destruction already wrought is merely the side effect of temporary conditions, to be followed by a period of rebuilding. This brings us to the meaning of a sequence of events commonly referred to as “world history.”

One fundamentally misses the point if one seeks it in the achievements of “pure reason.” We must abandon the overly simplistic view that knowledge grows autonomously through scholars, with each subsequent generation merely adding to the inherited stock of knowledge and skill. The fact that the Greeks neither wired, cabled, nor transmitted signals is typically explained by their supposed deficiency in physical science. Yet they built temples, sculpted statues, and carved gemstones of such beauty and delicacy that we, even with our most sophisticated instruments, can no longer match them. Without conducting experiments and relying only on everyday observations, they left behind edifices of wisdom that entirely shaped Western thought for one and a half millennia and still largely influence it today.

The teachable virtue of Socrates reappears, albeit somewhat thinner, in Kant’s “categorical imperative”; Plato's theory of ideas resurfaces in Schopenhauer’s aesthetics; the conceptual framework of chemical atomism originates with Democritus! Given this, is it more likely that they refrained from physics out of inability, or rather because they simply did not wish to pursue it? And might not their mysticism contain insights that we have forgotten?

Another example: Even today, all modern inventions would remain foreign to the ancient cultural nation of the Chinese had we not imposed them upon them. But if we open the works of one of their great philosophers, who flourished three and a half millennia ago, such as Laozi or Liezi, we encounter a depth of wisdom that makes even Goethe seem like an amateur by comparison. If they lacked the science with which one builds cannons, blasts mountains, or produces artificial butter, it is more plausible that they simply had no interest in such endeavors.

Behind every effort at knowledge stand the demands and goals of humanity, shaping and directing it, and only through understanding these purposes can we comprehend those efforts. For the progressive research of the modern age to emerge, the great shift in attitude that we call capitalism had to take place.

That the brilliant achievements of physics and chemistry have served only capital is no longer in doubt for thoughtful minds today; and it would not even be difficult to demonstrate that the same tendency exists within the prevailing doctrines themselves. The distinctive achievement of modern science — the replacement of all intrinsic qualities with mere quantitative relationships — merely replicates, in the realm of epistemology, the fundamental principle of a will that sacrifices the shimmering richness of spiritual values — blood, beauty, dignity, fervor, grace, warmth, and motherhood — to the fabricated value of that imagined power embodied measurably in the possession of money.

For this, the term “Mammonism” has been coined; but only a few have realized that this Mammon is an actual entity, which has seized humanity as its instrument to annihilate the life of the Earth. On this point, let us permit one further clarifying remark.

If “progress,” “civilization,” and “capitalism” merely represent different facets of a single will, we might recall that their bearers are exclusively the peoples of Christendom. Only among them were invention upon invention accumulated, “exact” science — meaning quantitative science — flourished, and the relentless drive for expansion arose, which seeks to subjugate non-Christian races and exploit all of nature. Thus, the proximate causes of world-historical “progress” must lie within Christianity itself.

Although Christianity has always preached love, a closer examination reveals that this love, at its core, is merely an unconditional “Thou shalt” of respect — respect exclusively for humanity, for man in a deified opposition to all of nature. Under the guise of human worth or “humanity,” Christianity conceals what it truly means: that all other life is worthless except insofar as it serves humanity! Its “love” did not prevent it from pursuing the nature worship of the pagans with deadly hatred in earlier times, nor does it prevent it now from dismissing the sacred customs of childlike peoples with contempt.

Buddhism, as is well known, forbids the killing of animals because animals, like us, share the same essence. By contrast, an Italian who is confronted with such objections when torturing animals to death replies, senza anima (“without a soul”) and non è cristiano (“it is not Christian”), for the devout Christian acknowledges a right to existence only for humanity. The ancient piety, which once accompanied this doctrine and still lingers in the huts of the common folk, was denied to its flagbearers. Instead, Christianity nurtured and allowed to grow into a world-darkening power that terrifying megalomania which deems even the bloodiest outrage against life permissible, indeed obligatory, as long as it promotes human “utility.”

Capitalism, along with its precursor, science, is in truth a fulfillment of Christianity. The Church, like capitalism, is merely a union of interests, and the monon of a desacralized morality signifies the same unity of a life-opposing ego that, in the name of the sole deity of the spirit,1 declared war on the multiplicity of the world’s countless gods. Today, however, this war is coupled with a blind idea of universalism, whereas previously it at least honestly faced the world with the threatening posture of a judge.

All those blossoms have fallen

From the North’s chilling gale.

To enrich but one among them all,

This world of gods had to perish.

The one who believed himself enriched by trampling the blossoms into the dust is, as has now become clear, humanity as the bearer of the calculating, acquisitive will. And the gods, whom he separated from the tree of life, are the ever-changing souls of the sensory world, from which he has torn himself away. The hostility toward images, which the Middle Ages cultivated as self-flagellation within, had to manifest outwardly once it achieved its goal: breaking the connection between humanity and the soul of the Earth.

In his bloody blows against all fellow creatures, he only completes what he had already done to himself: sacrificing his interconnectedness with the creative diversity and inexhaustible abundance of life for a rootless detachment, a world-alienating spirituality that stands above it all. He has turned against the planet that gave birth to him and nourishes him, and even against the cycle of becoming of all celestial bodies, because he is possessed by a vampiric power that entered the “music of the spheres” as a piercing discord.

At this point, however, it becomes clear that Christianity represents only one epoch in a much older process of development, through which something that began long before came to a sudden conclusion and, particularly for Europe, took on its formative character.

The force that rises up from within humanity against the world is as old as “world history” itself! The developmental trajectory called “history,” which departs from the circular path of natural occurrences and is incomparable to the fate of other living beings, begins at the very moment when humanity loses the state of “paradise” and suddenly finds itself standing outside, with alienated eyes, in the cold clarity of daylight — torn away from the unconscious harmony with plants and animals, waters and clouds, rocks, winds, and stars. The myths of almost all the peoples of the world suggest bloody struggles, even in prehistoric times, between the “solar heroes” who bring a new order, and the chthonic powers of fate, which are subsequently forced to descend into a lightless underworld.

Indeed, a Jesuit, in a strange but instructive reversal of facts, accused the myths of the Greek Heracles of preemptively stealing from the life story of the Christian redeemer! Yet this is everywhere the one and the same meaning of the transformation with which “history” begins: that spirit rises above the soul, wakefulness above the dream, and a striving for permanence above the life that comes into being and passes away.

In the millennia-long process of the unfolding of the spirit, Christianity was merely the final and decisive stage, after which the development transitioned from the state of still powerless understanding to the state of the “bound Prometheus,” whom Heracles set free! At this point, even the will was infused with it, and in the murderous deeds that have echoed unceasingly through the history of nations ever since, it has become apparent to anyone not entirely blinded: an otherworldly power has broken into the sphere of life.

To open our eyes to this is the only thing we can do. We must finally stop conflating what is deeply divided: the powers of life and the soul with those of reason and will. We must recognize that it is the very nature of the “rational” will to tear the “veil of Maya” into pieces, and that humanity, having surrendered itself to such a will, must in blind rage devastate its own mother, the Earth, until all life — and ultimately humanity itself — is delivered over to nothingness.

No doctrine can return to us what has once been lost. The only path to reversal lies in an inner transformation of life, which is beyond human power to bring about. We mentioned earlier that the ancient peoples had no interest in spying on nature through experiments, enslaving it in machines, and cunningly defeating it through itself; now we add that they would have abhorred it as hubris, wickedness. For them, forest and spring, rock and grotto were filled with sacred life; the chills of the gods wafted down from the peaks of high mountains (and for this reason — not out of a lack of “feeling for nature” — they did not climb them!). Thunderstorms and hailstorms intervened threateningly or auspiciously in the course of battles.

When the Greeks built a bridge over a river, they sought forgiveness from the river god for humanity’s presumption and offered a thanksgiving sacrifice; desecration of trees was bloodily atoned for in ancient Germania. Alienated from the planetary currents, modern humanity sees all of this as mere childish superstition. It forgets that these interpretive fantasies were fleeting blossoms on the tree of an inner life that harbored deeper knowledge than all its science: the knowledge of the world-creating weaving power of all-binding love. Only if this love were to grow again within humanity might the wounds heal that have been inflicted by the matricidal spirit [Geist].

Scarcely a hundred years have passed since the advent of those who, as though springing anew from hidden wells of the depths in many hearts, bore unforgettable dreams as youthful sages and poets — those whom we, misunderstanding them, call “Romantics.” Their hopes were in vain, the storm has subsided, their knowledge is buried, the tide has receded, and “the desert grows.” But, like them, ready to believe in miracles, let us consider it possible that a future generation may yet see realized what, in the words of the seer, Eichendorff described as the birth pangs in his Ahnung und Gegenwart (Presentiment and Presence):

“To me, our time seems to resemble this vast, uncertain twilight! Light and shadow still wrestle mightily with each other in wondrous forms, as yet undivided; dark clouds draw heavily between them, laden with fate, uncertain whether they bring death or blessing. Below, the world lies in broad, steaming stillness, waiting. Comets and marvelous celestial signs reappear, ghosts once more roam through these nights, and mythical sirens themselves rise anew above the sea’s surface as before approaching storms, singing their songs. Everything points, like a warning with a bloody finger, to a great and inevitable calamity. Our youth enjoys no carefree, light-hearted play, no joyful peace like our fathers; life’s gravity has gripped us early. We were born into battle, and in battle we shall perish — overcome or triumphant. For out of the magical haze of our culture, a war-specter will form itself, armored, with a pale deathly face and bloodied hair. Those whose eyes are trained in solitude can already see, in the wondrous contortions of the smoke, its outlines rising and quietly taking shape. Lost is the one whom time finds unprepared and unarmed; and how many, who are soft and inclined to pleasure and joyful poetry, would so gladly reconcile themselves with the world — who will, like Prince Hamlet, say to themselves: ‘Alas, that I was born to set the world right!’ For the world will one day fall out of its joints, an unheard-of battle between the old and the new will begin, and the passions, now creeping in disguise, will throw off their masks, and flaming madness, as if Hell itself were unleashed, will hurl itself into the chaos with torches of fire. Right and wrong, both sides, will blindly mistake each other. Miracles will finally occur for the sake of the righteous until, at last, the new yet eternally old sun breaks through the horrors; the thunders will roll only distantly among the mountains, the white dove will fly through the blue air, and the earth will rise, tearfully beloved, like a liberated beauty into new glory.”

In Klages’ mature thought, the concept of Geist (commonly translated as “spirit” or “mind”) occupies a pivotal and deeply critical role. Unlike its usual connotations as something noble or transcendent, Geist for Klages represents a destructive force in human existence, antithetical to the vitality of life and soul (Seele). His critique of Geist is central to his philosophy, which opposes the mechanistic and rationalistic tendencies of modern civilization. His masterwork on the concept of Geist is “Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele” (The Spirit as Adversary of the Soul). Published in 1929, this monumental work is considered the pinnacle of his philosophical thought and offers a comprehensive critique of Geist as a destructive force in human culture and life. The conclusion of this text introduces this theme.