Some Personal History

I have the sense that my reflections are sometimes a bit too autobiographical, but I also think that they might reach people for whom they’ll resonate, and who might find them helpful. I promise that there will be some conclusions at the end of the wandering. Also, this whole piece is too long, and I’m sorry.

Christ found me in the depths of despair after the death of my father almost 40 years ago. I may still always be waiting for a “road to Damascus” moment, but in retrospect, I actually had one. Then an unbeliever — a young man with a typical trajectory for modern adolescent seekers that had taken me through Crowley, psychedelics, Zen Buddhism, Be Here Now, and a vague neopaganism — I bent my head in solitude and cried and prayed to the Unknown God: “I don’t know who you are, but if you don’t help me, I’ll die.” And, typically in my experience of such prayer, the darkness did not lift immediately, but it did lift; and never again, in the throes of all life’s tragedies thus far, have I ever found myself in a like pit of darkness (though I have come close).

The way forward that presented itself was faith in God, in the One God of the world’s personalist Semitic monotheisms. Of course, raised in the fading cultural ambience of Christian faith in middle-class 1970s America, a monotheism was my first resort for serious religion once it was a matter of existential survival and not just youthful spiritual flânerie. Serendipity brought me first to Islam, but I got to Christianity eventually, and soon to a living ancient form of it, Orthodoxy. (I never gave Catholicism a fair shake at that time, but later I remedied that oversight.)

However, I was dogged at every step by problems with the philosophical theism that seemed to comprise one essential strand of Orthodox (and broadly, mainstream classical Christian) tradition. This tradition presented me with two distinct worlds or themes, which, though it gave them as inseparably linked, or even as merely different expressions of the same truth, I could never reconcile without a tension so great that it seemed to strain my mind and my soul to the breaking point. These worlds were, on the one hand, the world of affective faith and simple-hearted religious belief, the spiritual world especially of Russia’s unlettered ancient startsi, or elders, the beautiful-souled, wilderness-dwelling exemplars of repentance, humility, and silence; and on the other hand, the world of philosophical reflection on and distillation of that world into philosophically shaped dogmatic assertions about the metaphysical truths underlying it. (The Nicene Creed that we Orthodox sing every Sunday is one such distillation, though Orthodox hymnography in general is so freighted with theology that it’s a bit overwhelming sometimes.)

The Honeymoon Ends

Eventually, as the initial honeymoon of conversion wore off (be sure that if it hasn’t yet for you, it shall, so gird your loins), the sheer joy and gratitude of having found a basic answer to death, loss, and absurdity was joined with nagging questions. Those questions focused at first on the problem of evil and theodicy — that is, the justification of the goodness of an omnipotent, omniscient God in the face of the manifest actual evils of the world. I will not rehearse this problem in depth, or the various solutions offered to it in so-called “classical” theism. Whether because of my own invincible ignorance, or because (as I do prefer to think) none of those solutions really work, the problem became torturous for me.

My father had been an academic deeply concerned with the Shoah. Something must have carried on in me from him, because my doorway into Orthodox faith was the story of the New Martyrs of the Communist yoke in Russia. One of the most powerful books that introduced me to Orthodoxy was Russia’s Catacomb Saints (I was also deeply affected by the lives and writings of the Romanian “saints of the prisons,” especially Fr Georges Calciu of blessed memory). So the sense of the reality of evil in the world was a deep presence in my heart as I came into Orthodoxy, as was the witness of those martyrs to an invincible love and truth in the midst of the most profound desolation.

The knowledge that the faith had lived in Russia and elsewhere in the Communist world in spite of inconceivably brutal torment, in the hearts of people who faced death and the obliteration of everything they loved with an inextinguishable light in their souls, accompanied my early experiences of Great Lent and Pascha. As I waited that first Pascha in a darkened church, with the silent crowd in an émigré parish, surrounded by ancient icons rescued from the Godless ones by refugees, and heard the clergy within the altar area begin to chant Thy Resurrection, O Christ our Savior, the angels in Heaven sing, I knew that I would become Orthodox. I get goosebumps and tears rise in my eyes as I think of it, even to this day.

All this is to say that evil, and its answer (God’s answer, the word of the Cross and the empty tomb), were central to my conversion, and later, central to my troubles with the intellectual expression of the faith. Because those intellectual expressions — as much in Orthodoxy as elsewhere in Christian theological tradition, though with important caveats — all failed. There was (and is, I believe) no way to square the goodness of God with God’s all-powerfulness as literally construed by discursive theology.

“An all-good God would wish to prevent all senseless evils. An all-powerful God could do so. But senseless evils exist. Therefore, God is not all-good, or God is not all-powerful, or God does not exist.” I might add, “Or senseless evils do not exist,” but I do not accept the theodicies that assert that — I have seen and learned too much; my heart rebels, and I must listen to it.

(Philosophically inclined readers, I beg your indulgence; the chances are very great that I have heard your well-thought-out responses to this problem that claim to rescue classical theism, and I reject them.)

But I knew that God existed, with the knowledge of the heart; I did not require any proofs of God’s existence for my mind. Perhaps this was the result of an unconscious operation of Newman’s “illative sense.” I also knew that God is all-good with perfectly certain knowledge; if God were not all-good, God would not be the God Who was revealed to me that Paschal night, the God Who, in retrospect, my heart felt touching me in every beauty of the world and my life. (Jung’s “theodicy” in Answer to Job, which locates evil in God, has always struck me as monstrous.) So I concluded, to avoid the final immolation of reason, that the tradition must be wrong in the way it speaks about God as “all-powerful.” (There are deeper problems in theodicy, of course; I am sketching a brief picture. Others might have chosen different parts of the trilemma on which to impale themselves.)

And thus began my journey with dissident, unorthodox theism. As I entered this world, some other theological issues with classical theism began to become apparent to me: the problem of the reality of human freedom in the context of classically construed divine omnipotence, omniscience, and timelessness being one of them; the problem of God’s relationship, if He is truly “immutable” as classically conceived, with the created world being another. Increasingly it seemed to me that the God proposed to me by classical theism was incompatible with the God proposed to me by the Gospel and by traditional Orthodox piety as it manifested in the life and practical teaching of the saints I had come to love so deeply.

My first stop was open theism, which turned out to be essentially an evangelical Protestant attempt to address some of these issues using the resources of the 20th century “philosophers of process,” most notably Alfred North Whitehead and Charles Hartshorne. I quickly saw that this was a halfway house: once I admitted the kind of doctrinal revisions suggested by the open theists, there was no way to avoid the progress into deeper waters — into the process philosophers themselves and into the process theologians who took Whitehead much more radically than the open theists. David Ray Griffin’s books Unsnarling the World Knot; Parapsychology, Philosophy, and Spirituality; and God, Power, and Evil prompted a revolution in my thought. I found process thought immensely compelling — a philosophical theology rooted in process, change, and freedom as aboriginal elements of the universe and of God, a one-stop shop for the resolution of impossible theological quandaries and the reconciliation of religious faith and scientific naturalism.

The problem was that it didn’t stop there. My first deep issue with Whitehead’s God was not the usual one (many classically theistic believers simply ask, “Is this a God worthy of our worship?” but I never had any trouble answering that in the affirmative). Instead, it was technical. In Whitehead’s metaphysics, God as the most-moved mover (Hartshorne’s description, but very apt) receives and preserves eternally all the events of the cosmos in God’s “consequent nature.” This is the locus of objective immortality. But I saw that this would require that God also preserves forever all the universe’s greatest horrors and evils, that evil (even if only evil as suffering undergone) would be objectively immortal in God. I had the opportunity to discuss this issue personally with John Cobb, one of the most prominent 20th century process theologians, and while I do not now recall his exact answer, I was not satisfied. It felt viscerally to me that this was a flaw, a fundamental flaw in Whitehead’s theological vision, and it made me wonder what other such flaws I had overlooked in my enthusiasm.

So I went deeper down the rabbit hole, into process naturalism, the position of thinkers such as Henry Nelson Wieman (whose name is not well-known now, but who was a very prominent liberal 20th century theologian). Wieman’s position was that we can say very little about God, but we can identify (and he did very painstakingly identify, examine, and describe) a creative process at work in the universe that is the source of all the values we can perceive. This creative process he proposed that we should name as “God” — God may be more than this, but we can confidently say that God is at least this. So his is effectively an impersonal theism, a form of theistic naturalism. In companionship with the existentialism of another liberal theologian, Rudolf Bultmann, Wieman’s parsimonious metaphysics made an extremely austere expression of Christian faith, compatible with the most thoroughgoing scientific naturalism, even physicalism. Perhaps, I thought, this farthest end of metaphysical parsimony could save my belief in God from the problems generated, it seemed, by all varieties of philosophically informed natural theology.

Alas, that too was wrong. I saw that even Wieman’s extraordinarily minimalist theistic metaphysics was dogged by at least one fundamental problem, namely this: Wieman claims that he has identified a process at work in the universe that produces all values, and is therefore worthy of our “ultimate commitment,” and that this process can be properly identified as “creative interchange.” His elaboration of it is remarkably precise and subtle and perceptive. And yet, “creativity” and “change” do not lead inexorably to the creation of values; they can lead just as easily, and looking at the world, one might say, much more often lead, to the creation of disvalues and the destruction of values already brought into existence by the cosmic process. “Creativity” is not trustworthy in itself. It is not the proper object of our “ultimate commitment.” Certainly, my child, as a person, is of greater value than the abstraction of “creativity.” If embracing “creativity” led me to destroy or harm my child, so much the worse for “creativity.” I choose the concrete person.

At this point, the nadir of my descent, as it were, I finally grasped a fundamental truth: all philosophical elaborations of the content of the faith are provisional, incomplete, and indeed, broken and deceptive in certain regards. In short, philosophical cogency and consistency cannot be the criterion of truth, and conversely, philosophical incoherence and contradiction cannot be the criterion of error.

Here’s why this insight may be valuable to some of those who are flocking to traditional Christianity, and this is why I’m really relating any of this personal history at all.

Approaching the Faith Today

The specific thinkers and theological approaches that I burned through in my attempt to make rational sense of the faith are peculiar to me; others will have quite different histories, but perhaps a similar underlying error: seeking to solidify what we must honestly admit is a tenuously held, fragile faith by expressing it with complete, consistent intellectual clarity.

Of course our faith is fragile and tenuous. We live in a world where the last vapors of culturally operative and normative Christianity have dissipated. A true gulf separates us from the beforetimes when faith could be taken for granted as a common existential foundation for the culture. The life that we live, the media to which we are exposed, the intellectual and existential and moral atmosphere that surrounds us, is not merely hostile to traditional faith: almost worse, it is uncomprehending, indifferent. It is only in rapidly evaporating ponds of culture that we could even assume, for example, that an oblique but obvious allusion to the Sermon on the Mount will evoke any memory, let alone any emotional and moral resonance.

So there’s no sin in the weakness of our faith. But it’s a dead end to attempt to strengthen it by pinning our hopes on an exhaustive rational exposition and expression of it; literally a dead end — that is, it does not lead to Christ; it leads in the other direction. There will always be something that escapes. There will always be holes, disappointments, contradictions, inconsistencies. The grander the theological architecture, the more serious these lapses will be, because they will be more subtle, the structure itself more dazzling and comprehensive, more inviting of our “ultimate commitment” — which properly belongs only to God, not to a rational construct, however brilliant, however insightful. We are so struck by the cathedral that we miss the cave, the mountain, the ocean, and the unhewn stone; so struck by the choir that we miss the wind and the chorus of birds. We turn from what we cannot master, to what we believe we can master, from icon to idol. Our belief that we can master it is false. We do not master it; it masters us, and if we do not get free, we lose our souls.

There is something inherently idolatrous about a fascination with theology as a rational exercise. Really, it was a great blessing for me to encounter, in the various ways I did, the failures of so many forms of classical and dissident philosophical theism. A great blessing, because it threw me back, ultimately, onto my heart.

The question is how to enter more deeply into the faith. We enter it with some ideas about it that are compelling (at least for us, and at least at this moment), but it’s our hunger for God in the midst of beauty and evil, love and death, that really draws us. The ideas will let us down eventually, however excited about them we are when we first encounter them.

Part of the problem is that we don’t really even understand them. We take up the traditional doctrinal formulations, for example, and we handle them as if they were translucent to our penetrating intellect, as if we really grasped them. We don’t. We manipulate, explicate, criticize, and deploy them all from within a framework of fundamental ignorance — and I don’t mean ignorance as a lack of information; I mean ignorance as an unenlightened heart. And we can acquire more and more information — study languages, for example, become scholars, develop our rational and critical acuity to awe-inspiring degrees, write articles and books of blazing and incisive articulate cleverness that scatter all their foes before them1 — and yet remain fundamentally spiritually ignorant because our hearts have remained unchanged.

The whole point of the faith is to change our hearts, to make us more able to love God, other people, and the whole created world. Greater love means greater understanding; we can’t understand what we don’t see with the eye of love. The fundamental point of the praxis of Christianity is the transformation of the heart, not the acquisition of knowledge — and still less the accumulation of opinions. Indeed, the tradition as I receive it asserts unequivocally that knowledge without love is diabolical (quite literally, if you look more deeply into the etymology of that word). “The devils also believe, and tremble,” according to the Apostle James.

The real exemplars, then, are the saints. I mean something very particular by that. I mean the numinous human beings held up for veneration by the Church whose beauty is actually recognizable to the eyes of your heart. This is how the light of Christ reaches us: through the souls of those who have given themselves to him and therefore can fundamentally attract us to him.

I despair a little at describing this. If you know you know, and if you don’t, I can only pray that you come to know it. If you have not had the experience of falling in love with a saint, really seeing them, really feeling your heart going out of itself in a movement of veneration and gratitude and wonder that they exist, there is not much I can tell you except that in my experience, all the familiarity in the world with doctrine and praxis on an external level really means nothing. “It reminds me of straw.”

So when I go down some theological rabbit hole and come up against the inevitable problems, after I shed some tears and spend some nights in confusion, walk around for a few days making my family wonder what’s going on, rack my brains, order a few more books for the pile, stand stony-hearted in the Liturgy — eventually I come back to the saints.

Not the great dogmatists. Not the elevated mystical theologians. I can’t understand them. I don’t know how to forgive my neighbor. I don’t know how to love anyone, not much, and certainly not my enemies. I still go into thought spirals of resentment for things that happened years ago. I still chafe at making sacrifices for my family, let alone for strangers. How could I expect to pick up St Gregory of Nyssa, or St Gregory Palamas, or St Dionysios the Areopagite, and understand anything there? All I will do is misunderstand it. And I’m pretty smart. I’m good at this “rational understanding” game. Too good at it. It’s my comfort zone. But the heart is never a comfort zone. The heart is where it’s real. The heart is where there’s no evasion. The heart is where my arguments and my pride don’t work because the heart is like the earth of a garden or like a child or like a lover — it doesn’t resonate with your words; it resonates with your actions, your being, your energy, your reality. But it is also therefore where I can let go of my fear, my grief, and my despair.

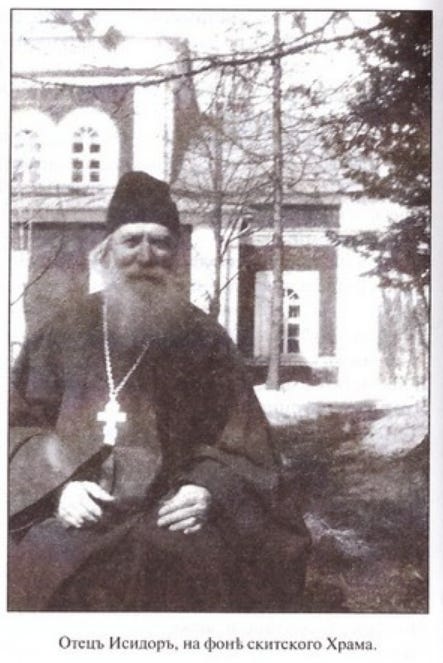

So the saints I go to are not the theologians (or, more deeply, they are the true theologians, according to the maxim of Evagrius of Pontus: “The theologian is one who prays truly”). They are мужики, peasants. I was blessed to meet a few of them early on. One was the saint I took as my patron, Seraphim of Sarov. Another — one who just came to my heart again a few days ago — was Abba Isidore of Gethsemane Skete, a great 19th-century ascetic who was the spiritual father of Pavel Florensky, among other luminaries of Russia’s Silver Age.

I have “met” many more in the accounts of the monks of the “Northern Thebaid,” the Russian wilderness to which monastics in the tradition of St Nilus of Sora fled to escape the corruption and wealth of so many of their co-religionists. Yet there is no criticism or rebellion in them. Their focus remains on the love of God, and thus they are able to accomplish more than any reformer or revolutionary. But “accomplishing more” in this regard isn’t even their goal. Their “goal,” if any, is to love more, not to reform or revolutionize anything. “My place” where I habitually stand in Liturgy is in front of the icon of St Sergius of Radonezh. Every time I arrive in church and greet him and light a candle, I feel his silence, his love, his abandonment, his prayer, flowing over all the lands of Rus’, across all the centuries, travelling everywhere the émigrés and refugees have traveled, and coming at last to me; and he is alive, his eyes are alive, and he knows, he knows the truth of God, and he loves, he loves God, he loves me, he prays for me. And he is beautiful. And I love him. The saints are the Gospel written in human flesh and blood and bone.

I should say also that I am not advocating fideism or dogmatic indifference. It’s a secret third thing — neither rejecting the doctrine we don’t understand, nor accepting it uncritically and externally. It’s a form of patience and realism with regard to doctrine — accepting provisionally what we can accept with our whole heart, and for the rest, simply letting it be. Maybe it’s wrong; maybe we just don’t really understand it; God knows. But right now, we don’t need to know. Right now, we need to love as the Lord loved us. That’s enough to work on, don’t you think?

Brothers and sisters, don’t come for the theology: or if you come for the theology, stay for the saints, and then stay for the impossible task of loving as the saints teach us to love. Wrestle with theology if you must, but when you meet things you don’t understand, rest easy. Set it aside. You don’t have to accept it according to the meaning you think it has. Very likely, after you stay for awhile, you will develop the ability to understand what it means more deeply, and you’ll see that what you disagreed with was a misunderstanding. Or maybe this will never happen. Maybe you’ll keep disagreeing forever. (I often think this about myself with regard to certain problems.) Whatever. The program is not acquiring new ideas and opinions. The program is learning of the Lord, for He is meek and humble of heart, and we need rest for our souls.

This article was not written using AI.

Here’s looking at you, DBH.

I'm not sure why you sometimes hesitate to write auto-biographically, it's always far and away your most powerful and thought-provoking writing. I'm fascinated by your journey and I want further essays on each part of your journey (especially Sufism!). I have an icon of St. Seraphim of Sarov in my daughter's bedroom and I love him very much. My second son's middle name is Isidore, and as a hideously theoretical man who loves Florensky, I feel compelled to learn about his spiritual father now. Thank you for bringing him to my attention. I've always been drawn to the figures who wed the affective and the discursive: Gregory of Nyssa, Maximus the Confessor, Bonaventure, Soloyvov, Bulgakov, Florensky, and of course, the great mystic and conceptual artist Al-Ghazali. I'm obsessed with Nicholas of Cusa and his theological metaphysics, but I've also been to his body and placed my hand on his grave. Reading his texts goes hand in hand with praying for his help.

Anyway, please write more about your life!

I loved this article. I used to really enjoy reading theology books. I used to be enthralled by apologetics. And now, after a lot of hard life experiences in the last few years, I’ve come to find that it’s never the theologians who come to mind anymore when life is going poorly. It’s the poets, the novels, and the spiritual writings I’ve read. I have a piece on here about the limits of theology and the need for art. To me, the difference between the two is best found in Dante and Aquinas. Aquinas can define to me what love is. Dante shows me love, and in showing it to me, gives words to my own experience, my loftiest sensibilities and actions. Preachers can tell me how to live, but novels show me what life looks like from another person’s eyes. I am increasingly willing to say I don’t know the answers to the deep theological questions, and far more centered on trying to become more like the Christ I see in the gospels, because amazingly, that’s where so many of the great artists point me.