Translated from:

L’œil de Feu: Deux Visions Spirituelles du Cosmos

Olivier Clément

Fata Morgana, 1994

Liturgical Man

In celebration, where the Holy Spirit actualizes and manifests the death and resurrection of Christ, the “body of death” gradually becomes saturated with eternity, sketching its metamorphosis into a “body of glory.” The Church as a “mystery of life” establishes itself as a radiating center of cosmic existence. “Matter... receives within itself the power of God.”1 Under the translucent veil of the sacrament, the fallen modality of nature is reabsorbed into its glorified modality. Divine energies penetrate the water of baptism and the oil of holy chrism. Branches and flowers are blessed at Pentecost, fruits at the Transfiguration, wheat, oil, bread and wine on the eve of each feast. And everything culminates in the Eucharistic μεταβολή where bread and wine, in the conception of Eastern Christianity, are less “transubstantiated” than transfigured. For Saint Irenaeus of Lyon (2nd century), it is all of nature that we offer, so that it might be “eucharistized.”2 In the anaphora, Saint Cyril of Jerusalem (4th century) reminds us, “we make remembrance of heaven, of earth, of the sea, of the sun, of the moon and of all creation visible and invisible.”3 The Armenian liturgy proclaims: “Heaven and earth are filled with your glory through the epiphany of our Lord, God and Savior Jesus Christ... for, by the Passion of your Son, all creatures are renewed.” A “diaphany” of the Christ of glory, of the cosmic Christ, who responds to the expectation and impetus of creation.

Byzantine commentators, beginning with Maximus the Confessor in the 7th century in his Mystagogy, emphasize the correspondence between ecclesial liturgy and cosmic liturgy, between the church where sanctuary and nave are joined and the sensible and intelligible world. “The church... has for its heaven the divine sanctuary, and for its earth the nave in all its beauty.” “In return, the world is a church…”4 And man is called to identify himself with the church, and thereby with the world in its spiritual sense: he must make “of his body a nave, and of his soul the sanctuary where he offers to God the logoi of the universe.”5

In the Church, man thus learns a “eucharistic existence” where he can truly become priest and king. He discovers the sacramentality of being, the secretly transfigured world, and henceforth collaborates in its metamorphosis. His “eucharistic consciousness” — “in all things give thanks,” says the Apostle — seeks, at the heart of beings and things, the point of transparency where the light of the cosmic Christ can radiate. The invocation of the Name of Jesus draws everything into this great movement of offering: “Applied to the persons and things that we see, the Name becomes a key that opens the world, an instrument of secret offering, an imposition of the divine seal on all that exists. The invocation of the name of Jesus is a method of transfiguration of the universe.”6

The Blood and the Breath

The body of man is constituted, in its structures and rhythms, to become, as Paul says, “the temple of the Holy Ghost.”7 The physiology in question here is therefore a symbolic physiology where a spiritual corporeality is outlined and anticipated through the physical corporeality, illuminating it. Physiology, if you will, but of the “body of glory,” where each organ, each function expresses a spiritual reality that can only be inscribed in our instruments of observation in a negative manner. Just as the risen Christ was indeed present to Mary Magdalene or the disciples at Emmaus but “in another form,”8 so that they could only recognize him through love, likewise the electroencephalogram of a saint in prayer, who “sees” the glory of God in beings and things, will prove that it is neither a dream nor a hallucination, but something else: what? There exists no other “pneumatograph” than the “awakened” heart of man, in an experience of intelligence and love to which everyone is invited. To know, here, is to transform oneself.

To acquire the “knowledge of beings” (and, beyond that, union with God), two rhythms are used: that of breathing and that of blood.

The rhythm of breathing seems the only one that we can use — offer — voluntarily. The accounts of creation in Genesis emphasize the symbolic correspondence between the Breath of God — the Spirit — and the vital breath of man: “And the LORD God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul.”9 Trinitarian theology clarifies this connection: the Spirit, within the absolute, is the “Breath that utters the Word”10; thus, when the human breath, in the prayer known as “the Jesus Prayer,” utters the Name of the incarnate Word, it unites with the Breath of God, becomes its symbolic vehicle: little by little, man, as St Gregory the Sinaite wrote, begins to “breathe the Spirit.”11 The breathing of the immense is triggered in him, which poets sometimes sense:

Breathing: you invisible poem! Complete

interchange of our own

essence with world-space…12

It happens that the most demanding ascetics attempt to “descend below creation,” through a sort of cosmic humility, to discover there the Breath that carries the world. For a time, sometimes forever, they live only in the elemental, with rock and sand, dying as if by a mineral death until they pass “to the other side of the tapestry,” and then nourish themselves with an intense and gentle light which is no longer that of the sun and moon — “the city (spiritual) had no need of the sun, neither of the moon, to shine in it: for the glory of God did lighten it”13 — but their common source, the source of all beauty, “the Love that moves the sun and the other stars.”14

Blood, the biblical God reserves for himself. Its symbolism derives from its consistency, it is liquid like water; from its taste, it is salty like the sea; from its color and its warmth, it is red and hot like fire. It brings to mind the symbolic primordial ocean which the Spirit, the bird of fire, “brooded over.” It sketches a sort of conflagration, a “pneumatization” of the sensible. Man, murderer or sacrificer, sheds blood. Christ, in the fulfillment of sacrifice, in an immense movement of reintegration, sheds a vivifying, pneumatized blood, for the salvation of his murderers, that is to say all of us, daily murderers of love. “One of the soldiers with a spear pierced his side, and forthwith came there out blood and water,”15 of which the earth, says Sergius Bulgakov, was the mysterious receptacle, a true “cosmic grail.”16 Pneumatized water of baptism, pneumatized blood of the eucharist which is “Spirit and Fire,” say the Syriac liturgical texts. Henceforth the divine-human blood mingles with ours to confirm its rhythm as celebration.

“Praise him with the timbrel and dance!”17 Dance of breath and blood, timbrel of the deep “heart,” of which we must now speak.

The “Heart”

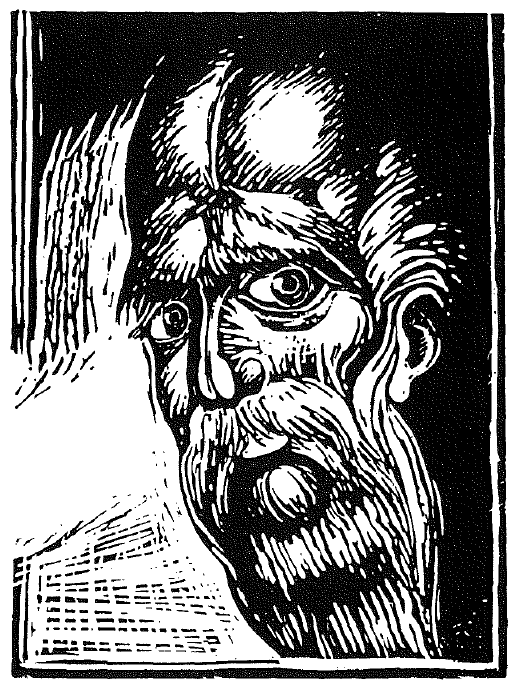

The “heart,” according to the ascetic tradition of Eastern Christianity, constitutes, in a real symbolism, the most central center of man, his deepest depth. It is in the “heart” that all his faculties must harmonize and unify, for all the faculties of man are required to participate in knowledge. It is there that, after a long ascesis of purification, this interior heaven vaster than cosmic spaces can open, for transcendence fills it with its radiance. “The spiritual country of the man with a purified soul is within him. The sun that shines in him is the light of the Trinity... He marvels at the beauty he sees in himself, a hundred times more luminous than the splendor of the sun. This is the Kingdom of God hidden within us, according to the word of the Lord.”18

The “deep heart” thus appears as a kind of “supra-conscious,” a “transconscious,” aspiring to open itself to the abyss of divine light. There is great convergence with the observations of “existential psychoanalysts” (like Victor Frankl19) for whom the deepest unconscious contains a transcendent dimension and speaks of God, so that the true neurosis from which so many of our contemporaries suffer would be a “spiritual neurosis,” due to the absence of logos, the absence of meaning. In a similar perspective, a Jewish psychoanalyst, Eliane Amado Levy-Valensi, notes: “Freudianism has shown that man censored the realities of sexual life because he was afraid of them. Very well. But there is a reciprocal to this theorem: it is that, if sometimes man distances himself from his sexual life, sometimes also he indulges and wallows in it because it frightens him less than his own deep reality...”20

In this unitary and symbolic anthropology, the heart is this “body in the deepest part of the body” of which Gregory Palamas speaks,21 that is to say, the seed of the “body of glory,” and the root of true knowledge, of which these ascetics, transposing to anthropology the Palamite distinction between divine “essence” and “energies,” say that the “essence” resides in the “heart,” while the intelligence of the head constitutes only its “energy...”

One must therefore consciously unite this “energy” to its “essence” (their dissociation defining the state of “fall”) by learning to “descend into the heart.” Thus is reconstituted the unity of the “heart-spirit,” the organ of true knowledge not only of God, but of all things in God, γνῶσις τῶν ὄντων: “What is knowledge? — The sense of immortal life. — And what is immortal life? — To feel everything in God... Knowledge connected to God unifies all desires”22 or rather, to take up again, with these ascetics, but in a biblical perspective, the Greek tripartition, truly Indo-European, of faculties, the unification is that of νοῦς, the intellect, of θυμός, strength, and of ἐπιθυμία, desire...

It would be rather futile, it seems to me, to identify the union of intelligence and heart with an integration of the two brains, the archaic brain being considered as the seat of intuition. First because we are dealing here, I repeat, with a symbolic physiology (of which the integration of the two brains would be only a trace), then because the ascetic truly becomes conscious of the spiritual heart, in his chest and in his “reins.” The Methodos,23 a Byzantine text that probably dates from the 12th century, gives the following instructions: “Resting your beard against your chest, direct the eye of the body at the same time as your mind to the center of your belly, that is to say, to your navel, compress the inhalation of air that passes through the nose (...) and mentally search the inside of your bowels for the place of the heart, where all the powers of the soul like to gather. (...) As soon as the mind has found the place of the heart, it sees the firmament that is there...”24

In later texts, there is no longer any question but of the physiological heart as the symbolic seat of the spiritual heart (with a certain distinction however, which Basil of Poiana Mărului would emphasize at the end of the 18th century). Here are two texts, one from Nicephorus the Solitary (13th century), the other from one of the principal renovators of this “method” in the following century, Gregory of Sinai.

From Nicephorus: “...sit down, collect your mind and introduce it into your nostrils; this is the path that breath takes to go to the heart. Push it, force it to descend into your heart together with the inspired air. When it is there, you will see the joy that will follow...”25

From Gregory: “...sit on a low seat, drive back your mind from your reason into your heart and hold it there, while laboriously bent (...) you pronounce in your mind or in your soul the prayer of Jesus.”26

Gregory advises mastering breathing to overcome “the tempest of breaths” that rises from the superficial heart. Summarizing an entire tradition, he asks for the temporary rejection of all thought, even if it be good, for thought gives a “form” to the “heart-spirit,” narrows it, closes it to the infinite: “Pay no attention to them (thoughts) but, as much as you can, hold your breath, enclose your mind in your heart and practice the invocation without truce or respite...”27

It remains to explain the most archaic indication which situates “in the reins” the “place of the heart,” which is not without importance for our subject — the knowledge of cosmic logoi — and for its location, if one thinks of the role of hara in Japanese asceticism.

Saint Gregory Palamas, defending in the 14th century, against spiritualist humanists, the monks who concentrated “on the reins,” explains that it involves a becoming aware of and transfiguration of desire, of the human and cosmic eros: “You make your own,” he says to God, “the desiring part of my soul, you bring this desire back to its origin, so that it may leap toward you, attach itself to you... Those who have established their soul in the love of God, their transformed flesh shares the spirit’s soaring and joins with it in divine communion. It becomes, too, the domain and house of God.”28 Palamas maintains, however, that the word “heart” is used here improperly, and that the spiritual heart has no other place than the physical heart.

But there is another possible interpretation, which would be purely biblical. In the Hebrew Bible, indeed, rehem designates the maternal womb, the matrix; the sensitivity connected to it, mercy, compassion in the strong sense of “suffering-with,” the mysterious bond of the mother with her child, is expressed by the word rahamim, which is nothing other than the emphatic plural of rehem. In many biblical texts, the heart is thus situated in the bowels: “My heart... melts in the midst of my bowels,” says a psalm.29 God is “enmothering,” translates André Chouraqui.30 To unite intelligence and heart “in the entrails” would then designate two fundamental attitudes, which are, moreover, complementary. On the one hand, the ultimate degree of apophasis, when the intellect, at the extreme of negative theology — which is still an intellectual activity — falls silent, becomes pure silent waiting; in every man, however virile he may be, the animus, to use Jung’s vocabulary, is then absorbed in a transfigured anima: this is the ultimate death-resurrection, and the intellect, the “heart,” is literally recreated in communion, in unity, by the thunderous coming of the Spirit.

And, on the other hand, to find the place of the heart in the bowels is to feel, in the deepest, most “enmothering” part of one’s being, an immense maternal compassion. If Christian Hellenism has above all emphasized cosmic beauty, the Syriac, Asiatic tradition has rather insisted on this boundless compassion: “What, briefly, is purity? It is a compassionate heart for all created nature... And what is a compassionate heart? — He says: It is a heart that burns for all creation, for men, birds, for beasts of the earth, for demons, for every creature. When man thinks of them, when he sees them, his eyes shed tears. So strong, so violent is his compassion (...) that his heart breaks when he sees evil and suffering inflicted on the humblest creature. That is why he prays with tears, at every hour (...), even for serpents, in the immense compassion that rises in his heart, without limits, in the image of God.”31

The intellect, united to the “enmothering” heart, is at once maintained in total dispossession, “Sabbatical” death32 beyond all “form,” and invested by the Name of the incarnate Logos which, far from giving it a particularizing “form,” draws it toward the abyss of the Father, source of divinity. The formula of invocation most employed in this process is the “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner,” in the sense of “take me into your merciful presence.” This formula can be:

Either, as recommended in his Enchiridion by Nicodemus the Hagiorite, pronounced entirely during inhalation, followed by a retention of breath where silence is established, with exhalation being rapid so as not to distract attention, for it is through inhalation (and retention) that the intellect returns to its own depths;33

Or, as explained in the last century by the Russian Pilgrim,34 synchronized with inhalation for “Lord Jesus Christ Son of God,” then with exhalation for “Have mercy on me, a sinner,” this synchronization serving another, more fundamental one, which concerns the rhythm of the heart: each word of the prayer being pronounced on a heartbeat. These two synchronizations can only harmonize if one slows down breathing, so that the duration of inhalation and then exhalation corresponds to at least three heartbeats (for the abbreviated formula: “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me”35) or four or five (for the formula indicated above).

Little by little the prayer becomes “spontaneous,” “uninterrupted,” and the “heart-mind” which at first quivers furtively under touches of fire of extreme sweetness, becomes inflamed, becomes light and an eye capable of seeing the light. The invocation identifies with the heartbeats without even being pronounced, “prayer beyond prayer.” The act of prayer is succeeded by a state of prayer. And this state reveals the true nature of man, the true nature of beings and things.

“When the Spirit establishes His dwelling in a man, he can no longer stop praying, the Spirit never ceases to pray in him. Whether he sleeps or wakes, prayer does not separate from his soul. While he drinks, eats, lies down, or engages in work, the fragrance of prayer exhales from his soul. Henceforth he no longer prays at determined moments, but at all times. The movements of the purified intelligence are mute voices that sing, in secret, a psalmody to the Invisible.”36 For the intelligence is transformed and as if infinitely dilated. “Sometimes,” writes the Pilgrim, “my limited mind becomes so illuminated that I clearly understand what formerly I could not even conceive.”37

“To Contemplate Nature”

Man now truly sees the logoi of things and their unity in the Logos. “From seeking comes vision, and from vision comes life, so that the intelligence exults and is illuminated, as David said: (...) in thy light shall we see light. For God (...) has sown in all beings what is His, by which, as through windows, He reveals Himself to the intelligence and calls it to go toward Him, filled with light.”38 “Thus one attains,” says the Pilgrim, “knowledge of the language of creation.” “Everything around me appeared to me in an aspect of beauty: everything prayed, everything sang glory to God.”39 The symbolism of the “language of birds” is universal, from Francis of Assisi to Iranian mysticism and the “councils of birds” mentioned in the Tibetan poem entitled The Precious Garland of the Law of Birds. The bird evokes the angel, and the angel designates the “vertical” knowledge of a being, the opening within it of the “celestial.”

“Thus the soul takes refuge as in a church and a place of peace in the spiritual contemplation of nature; it enters with the Word and, with Him, our Great Priest, under His guidance, it offers the universe to God in its spirit as on an altar.”40 Very close to us, Silouan of Athos (†1938) noted: “For the man who prays in his heart, the whole world is a church.”41

Man now ceases to objectify the universe through his covetousness and blindness. His presence exorcises, lightens, pacifies. Around him, nature is transformed and miracles sometimes bear witness that he constantly perceives each being and each thing as a miracle. Children, the most fearsome beasts, even plants commune with him. The Greek novelist Stratis Myrivilis transformed into a short story the true account of an “innocent” who, condemned for an almost involuntary crime, had purified himself in prison and had befriended a walnut tree he had planted, to the point that the tree, which lived from this bond, died instantly when the man was freed.42 A hermit of Patmos, at the beginning of this century, gave vipers little cups of milk to drink, and feared nothing from them. These stories are innumerable, they often belong to popular religion, but contain a great truth: the “contemplation of nature” transforms nature.

The conclusion, here, can only be an opening. Two questions seem to me to arise, and I wanted to suggest them through the awkward connections I have sketched here and there:

To what extent could this “knowledge of beings” through the “heart-mind” enlighten modern rationality, not to deny it, but to refine it and open it, to “seek a principle of explanation that does not dissolve the mystery of things, that respects and reveals existence and being instead of disintegrating them”?43 For it is the same intelligence, but freed from scientistic pretensions, freed from its self-sufficiency, penetrated, thanks to a long and methodical ascesis, by the light of the Logos, of the great divine Reason... Since the 13th century, the West has engaged in the conquest of the world, but it has forgotten the “divine energies” that could orient, finalize, transfigure its quest. In the aftermath of the Second World War, when Romania experienced a powerful renaissance of the “prayer of the heart,” young physicists from that country, I was told, practiced this invocation while conducting their research. Their approach was one of spiritual reintegration of matter. But they dispersed with the establishment of dictatorship, and I know nothing else about them. The indication, however, could be precious. Is spiritual knowledge not capable of opening new domains of intelligibility to science, and of bringing ends, a meaning, to a civilization that no longer knows what to do with its means, and risks the worst?

To what extent could the approaches of the Christian East, which I have just briefly evoked, serve as a link between the Western mentality, even Western Christianity, most often “a-cosmic,” and the great spiritualities of Asia? When I spoke of the contemplative uniting with sand and rock, I could not help thinking of the enigmatic gardens that Zen monks design in sand and punctuate with stones. Better than long speculations, a Japanese floral arrangement makes us hear the language of creation... It should be added that the Christian East, in the light of the Trinitarian “Super-unity,”44 has a conception of the person that differs both from the Western individual and from the Self of the Far East, and could undoubtedly facilitate their integration. For, as has been understood, the destiny of the cosmos, its possible fulfillment, is linked not only to man’s relationship with transcendence, but to relationships between men. The concept of man, as I have used it in this presentation, is never simply individual but always “communional.” The “heart-mind” is a heart in communion. There is no other possible atmosphere today for the authentic quest.

Saint Gregory of Nyssa, On the Baptism of Christ, PG 46, 581 B.

Against Heresies, IV, 18, 5.

Mystagogical Catecheses, V, 6.

Mystagogy, 3.

Ibid., 6

A Monk of the Eastern Church, The Jesus Prayer, Chevetogne, 1951, p. 94.

1 Corinthians 5:19

St Mark 16:12

Genesis 2:7

St John Damascene, On the Orthodox Faith, Patrologia Graeca 95, 60 D.

On the Contemplative Life, in Little Philokalia of the Prayer of the Heart, translated and introduced by J. Gouillard, Books of Life No. 83-84, p. 185.

“Atmen, du unsichtbares Gedicht! Immerfort um das eigne Sein rein eingetauschter Weltraum.”

Rilke, Sonnets to Orpheus I.3

Revelation 21:23.

This is, as is known, the last verse of Dante’s Divine Comedy.

St John 18:34

Bulgakov, Sergius. The Holy Grail and the Eucharist. Translated by Boris Jakim, Lindisfarne Books, 1997

Psalm 149:3

St Isaac the Syrian, Ascetical Homilies, 43rd treatise.

See for example Victor Frankl, The Unconscious God.

The Ways and Pitfalls of Psychoanalysis, Paris, p. 324.

Cited by J. Meyendorff, Introduction to the Study of Gregory Palamas, Paris, 1959, p. 247.

St Isaac the Syrian, op. cit.

Paleo-Greek text edited and translated by I. Hausherr in The Method of Hesychast Prayer, Rome, 1927, pp. 54-76.

Little Philokalia of the Prayer of the Heart, op. cit., p. 161.

“Treatise on Sobriety and Guarding of the Heart,” in Little Philokalia... p. 151

“On the Contemplative Life,” in Little Philokalia... p. 183.

Ibid.

“The Apology of the Holy Hesychasts,” in Little Philokalia... pp. 207-208.

Psalm 22:15

In his French translation of the Bible, published in the last ten years by Desclée de Brouwer editions, Paris.

St Isaac the Syrian, op. cit., 81st treatise

The “death of the intellect” or its “sabbath” is followed by its “resurrection,” by the “Sunday,” the “Easter” of supernatural life: St Maximus the Confessor, Theological Chapters, I, 36-60, PG 70, 1097-1103.

“Enchiridion,” in I. Hausherr, The Method of Hesychast Prayer, op. cit., pp. 106-111.

The Way of a Pilgrim

Ibid.

Little Philokalia... p. 82.

The Way of a Pilgrim

Callistus Cataphygiotes, “On Divine Union and Contemplative Life,” French translation by J. Touraille, Philocalic Collection, Ed. de Bellefontaine.

Op. cit., p. 57.

St Maximus the Confessor, Mystagogy, 7.

“On Prayer,” Contacts, No. 30, p. 128.

Cf. Stratis Myrivilis, “Pan,” in The Great Departure, Avignon, 1984, p. 96

Edgar Morin, interview about his work “Method,” Vol. I: “The Nature of Nature,” published in Le Nouvel Observateur on 05/10/1977, p. 102.

The expression is from Dionysius the Areopagite in The Divine Names.