The Eye of Fire (Part Two)

Olivier Clément

Translated from:

L’œil de Feu: Deux Visions Spirituelles du Cosmos

Olivier Clément

Fata Morgana, 1994

Introduction: Western Alchemy, Science and Art of Cosmic Transformation

In most “traditional” civilizations, alchemy is nothing other than the sacrificial science of earthly substances, the transfigurative liturgy specific to crafts dealing with apparently inanimate matter. We find it everywhere, from archaic Mesopotamia to ancient China and eternal India. In these “mythological” traditions, it does not occupy a special place: when Spirit is everywhere, it is clearly also in stone; when the one light, that of divine Intelligence, names itself in the sun, in the eagle, and in honey, what is surprising about it naming itself also in gold, that every metal should be a gold that is ignorant of itself and its very ignorance a “modality” of gold? When man’s only role is to worship in the undivided sanctuary of his body and nature, what is surprising about his “transmuting” lead into gold? Holiness too does not divide, and the “miracle” of transmutation reveals its omnipresence.

In metaphysical and mythological traditions, alchemy held no more importance than dance, which celebrated the holiness of rhythm, “validated” the circling worship of the stars through the dancers, and “transmuted” time into the sudden stillness of the body, the leaden sleep into the pure gold of an eternal instant.

But alchemy had a special destiny in “monotheistic”1 traditions, particularly in Christianity. Setting aside the “folkloric” remnants of European peasant societies, alchemy, or more broadly, hermeticism, seems to have been the only cosmological doctrine that survived in the Christian world. It was thus called to play a major role “beneath” a religion that emphasized the “contempt of flesh” and disregarded cosmology.

Indeed, throughout the early Middle Ages and until early Gothic art, alchemy did not oppose Christianity, but complemented it. Through it, the Eucharistic effusion radiated to the heaviest states of matter. Not only bread and wine, but stone, lead, and the limestone of bones and rocks were “transubstantiated.”2 Vivified by Christianity, alchemy gave it a “technical” application in the “psycho-cosmic” domain that it neglected since its goal was not to establish man in the world, but to free him from it.

Thus alchemy could not have survived in the West without Christianity’s prodigious initiatory effusion: just as the archaic house exists only through the hearth that allows it to communicate with “heaven,” so too is cosmology possible only around the “central” state through which one can transcend the cosmos.

But without alchemy, Christianity could not have “incarnated” in a total order: there would have been monks and saints, but no sacred conception of nature capable of giving the arts, crafts, and heraldry their character of “lesser mysteries.”

In these times when we are crushed by materialism, it may be urgent to recall that Christianity, in its highest flowering, not only accepted but vitalized a genuine illumination of materiality.

I. Insights Into the Doctrine

The Meaning of Gold

Contrary to what the historians of science repeat, alchemy was never, except in its fallen aspects, a primitive chemistry. It was a “‘sacramental” science where material appearances had no autonomy but merely represented the “condensation” of psychic and spiritual realities. Nature becomes transparent when one penetrates its spontaneity and mystery: on one hand it is transfigured under the flash of divine energies, and on the other hand it embodies and symbolizes those “angelic” states that fallen man only glimpses briefly while listening to music or contemplating a face. The symbol is not “overlaid” on things: it is their very structure, their presence and their beauty as they perfect themselves in God. For alchemy, the science of symbols, there was not, as sometimes claimed, a “material” unity of nature, but rather a spiritual unity — one might almost say a spiritual assumption of nature, since nature, ultimately, is nothing other than the locus of a metaphysical principle: through man it becomes the body of the Word, and like the bride of God.

This assimilation of matter is the key to the alchemical work; it helps substances to “precipitate themselves into the paternity of God”,3 that is, to incorporate, according to their mode, the maximum possible spiritual light. “Creatures must irrupt into paternity to become Unity and unique Son...” for “nature, which is of God, seeks nothing but the image of God.”4 “Copper can, by its nature, become silver, and silver can, by its nature, become gold: thus neither has rest nor respite until they realize this identity.”5 For gold is the most perfect of metals, the one whose luminous density best expresses, in the mineral order, the divine presence: by spiritual continuity, every metal is virtually gold and every stone, in God, becomes precious.

This transfiguration of nature, memory of Eden and anticipation of the Parousia, can in the here and now only operate in the heart of man, the central and conscious being of creation. Even now “the eye of the heart” can see gold in lead and crystal in the mountain, because it can see the world in God.

Alchemy, like all “traditional” sciences, was thus an immense effort to awaken man to divine omnipresence. Its importance lies in having emphasized this omnipresence at the darkest point of materiality: there where the perspective of pseudo-mystical “idealism” would least seek it — there, on the contrary, where, according to the analogical inversion of a “sacramental” vision, it becomes most concentrated and forceful at that point.

If metallic gold was sometimes obtained, it was therefore, quite simply, a sign: it was no greater miracle than that accomplished by a saint when his gaze metamorphoses the sinner. Just as the saint sees in the sinner the potential for sainthood, so too the wise alchemist saw in lead the potential for metallic sanctity, that is to say, gold. And this vision was “operative.”

But the alchemist was not trying to make gold. That was not the true meaning of his work. His aim was to unite his soul so intimately with that of metals that he could remind them of what they are in God — that is, that they are gold. The medieval alchemist literally fulfilled the Word of Christ: he proclaimed the good news to all creatures. “The stone is Christ,” repeated all the hermetic texts of the Middle Ages in unison. As a visionary of Christian gold, the alchemist could transmute any “imperfect metal,” but he did this very rarely because, being holy,6 he knew that the time of cosmic transfiguration had not yet come.

The true role of the alchemist was twofold: on one hand, he helped nature, suffocated by human downfall, to breathe the presence of God. Offering to God the prayer of the universe, he anchored Him in being and renewed His existence. The texts call him roi: as secret king, he strengthened the order of time and space, the fertility of the earth in grains and diamonds, as the kings of archaic societies did, as the emperor of China did until the threshold of the 20th century. On the human level, on the other hand, the alchemist, “awakening” substances and gold itself to their true nature, used them to prepare elixirs that gave “longevity” to the body and strength to the soul: “potable gold” was gold awakened to its spiritual quality, and reflected in its order the “remedy of immortality” that Saint Ignatius of Antioch used to designate the Eucharist.

The true role of the alchemist: to celebrate analogically a Mass whose species would not only be bread and wine, but all of nature. To make of the world, in the Christ, not only historical but cosmic, a eucharist.

The Logic of Alchemy

The logic of alchemy involved a double movement: “vertically,” it was a logic of symbol that brought manifestation back to its principle, appearance to the real, the world to God: a logic of reintegration. “Horizontally,” on the human-cosmic level, it was a dialectic of complementaries that everywhere emphasized the living tension of opposites: a logic of war and love.

A Logic of Reintegration

Alchemy involved, in sensation itself, the peaceful and detached love of the world. For the world of alchemy, like that of the “mythological” traditions whose heritage it transmitted, was both living and transparent, a great sacred body, an immense Anthropos in all ways similar to the small. Nature, one might say, was both the body of God and that of man. Everywhere was life, everywhere the soul, everywhere the holy breath of God. The blood of the sun made the golden embryo grow in the matrix of mountains. The seven planets in the sky, the seven metals they engender in the earth,7 the seven centers of life which, from sex to head, gravitate in man around the heart-sun, so many incorporations of the same structure of the Word; and the seven notes of the scale also manifested this “music of silence” that bathes creation, haloes the saints. and becomes motionless in gold.

This is why the alchemist, like the knight whose “proud kiss” delivers Mélusine from her divided state, revealed, in the nature that veils God, the nature that manifests Him.

“Learn that the goal of the science of the Ancients who developed both sciences and virtues is that from which all things proceed: invisible and immobile Divinity whose Will excites Intelligence; through Will and through Intelligence appears the Soul in its unity; through the Soul arise the distinct natures that in turn generate compounds. Thus one sees that a thing can be known only if one knows what is superior to it. The Soul is superior to nature, and it is through it that nature can be known; Intelligence is superior to the Soul, and it is through it that the Soul can be known; Intelligence can only refer back to what is superior to it, the One God who envelops it and whose essence is ungraspable.”8

This text, which specifies in a partially neo-Platonic tone the metaphysical background of alchemy, proves that it was essentially “interior”: the “Science of the Balance” weighs and fills at once the desire of the World Soul that each “nature” conceals, the desire of the divine Spirit that the World Soul conceals. The alchemist inverts cosmogony: dissolving material “hardenings” in pure life, he works in himself, through meditation on natural beauty and that “sympathy” which holds all things together, the unity of the World Soul, until making arise at its center, that is to say in his own heart, the solar fire of the Spirit. Then, through a higher cosmogony where Spirit, instead of becoming involved in matter, envelops and metamorphoses it, fire becomes incarnate: it transforms lead into gold, and man’s body into a body of glory. Alchemy is accomplished, as Henri Corbin noted, in a “physics of resurrection.”9

A Logic of War and Love

The proper domain of alchemy is thus essentially that of the soul, this human-cosmic environment of psychic nature that unites the world of “sensible” appearances to that of “spiritual” realities. This is the “intermediate world” of all traditions, the “mesocosm” of Iranian alchemy of Jabir, the Geber of the Latins. Now this “mesocosm” is governed by a logic of war, by essentially “dual” forces whose ceaseless combat is that of the two serpents of the caduceus. In this domain, the alchemical work will be entirely one of mediation: it will strive to transform war into love, so that it leads not to sterile death, but to glorious birth.

Nature’s “mode of operation” consists, in the universe of forms, in a continuous rhythm of “coagulations” and “dissolutions.” Form impresses itself on matter and matter dissolves it to offer itself to another form. Everything is alternation and transformation, evolution and involution, birth, life, death and rebirth, solve et coagula. “Nature takes its gambles with Nature” in a game of perpetual tensions that knot together, neutralize each other for an instant through their very opposition, then destroy themselves to arise again under new appearances. Nothing better symbolizes this “world of contraries” than the dragons devouring each other on the tympanums of certain Romanesque churches.

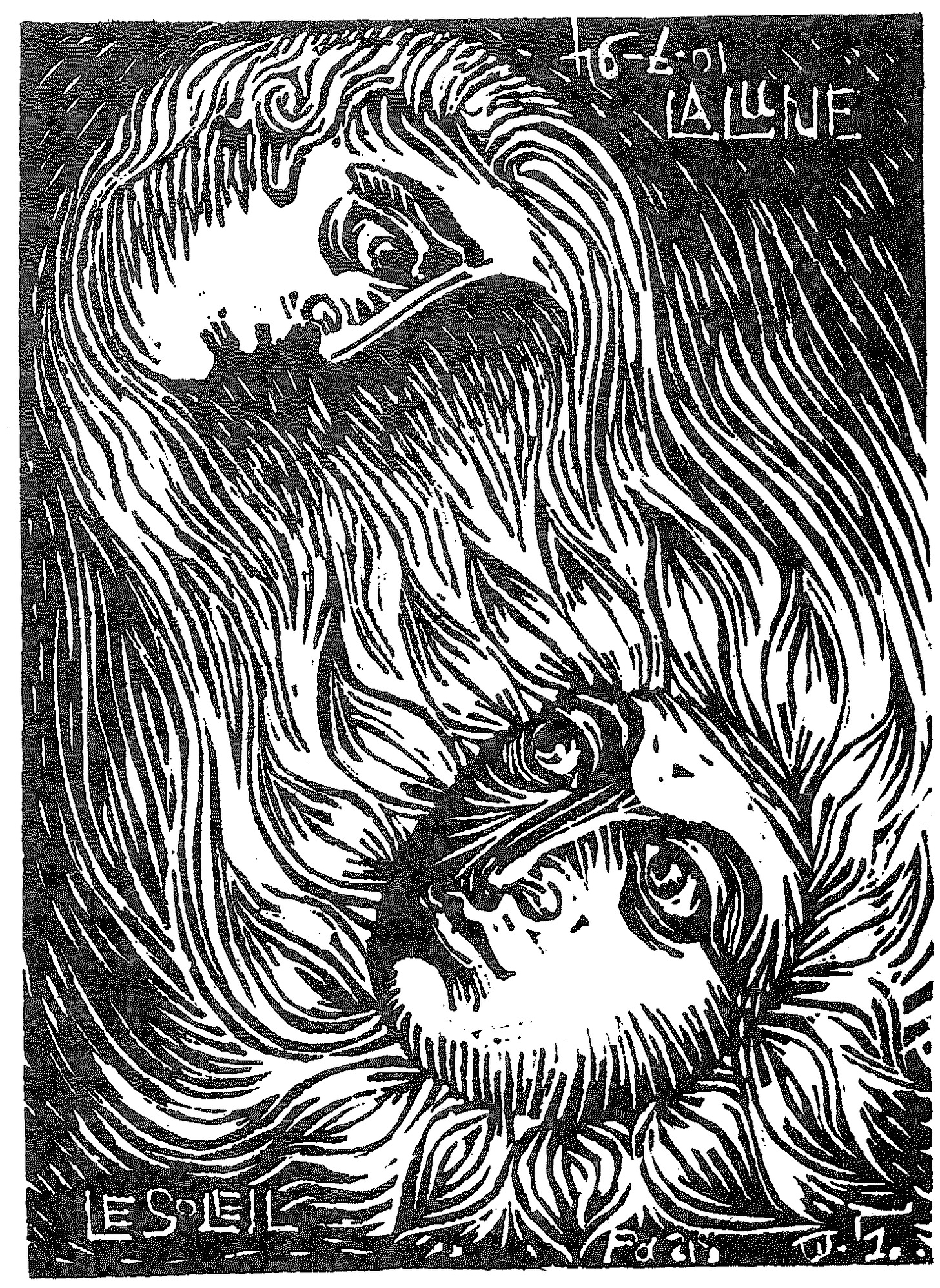

This ceaseless war — that presides over the metamorphoses of nature as well as human relations — alchemy brings back to the polarization of two “subtle” forces analogous to Chinese yin and yang: Sulfur and Mercury. Common sulfur, through its igneous nature; mercury, because it is fleeting and ungraspable; indeed incorporate these forces in their dynamic aspect. Gold and silver “crystallize” in their static aspect, as do the moon and the sun.10 These two poles participate closely on either side of the “intermediate world” which presents itself as their “field of force,” at the two divine poles that preside over “manifestation”: Pure Act and total Nature in Sufism, Shiva and his Shakti in Tantrism. Sulfur, relatively active or essential, represents in some way the Spirit, while Mercury corresponds more directly to the passive and feminine character of the Soul.11

Sulfur is connected to two fundamental tendencies symbolized by “heat” and “dryness.” Heat or sulfurous expansiveness affirms life and unfolds forms. Dryness or fixation embodies in the vital flux the divine “signature”12 that gives every being its face. Thus the principle of Sulfur, of Gold, of the Sun is a principle of stability and measure: it is, inherited from Greek thought, the virile principle of “limit.” But by itself it is only a receptacle that tends to close in on its emptiness, “it presents a harsh and terrible bitterness, where the astringent quality asserts itself as excessive, tight, hard attraction”;13 it becomes a force of individuation that transforms necessary protection into a refusal of life. In the human being, it ends up generating abstraction and egoism. For the seed to die, for the heart to melt, the intervention of the complementary force is therefore needed, of the feminine principle, Mercury.

To Mercury — the alchemists also called it Water, Silver and Moon — are connected “cold” and “humidity.” The cold or mercurial “contractivity” offers itself as a matrix to the “fixing” will of Sulfur; it envelops forms and gives them consistency and density. As for Mercury’s humidity, it is the power that “dissolves” these forms when their potentialities have hatched.

Mercury is wild and necessary life, ambiguous like the total Nature in which it closely participates. It is the “burning thirst” that, unable to be quenched, exasperates itself into self-destruction; the “viscous humidity” that prostitutes itself or dissolves through amorphous stagnation. In the human being, it is at once the desire for pleasure, devouring motherhood, gloomy sloth and the fascination with death. But it is also humble service to life, the creative submission of the “Virgin of the World”14 who ever serves the Lord.

“This Water subsists from all eternity,” writes Boehme. “It is the Water of Life that penetrates even death... It is also in man’s body, and when he thirsts for this water and drinks of it, then the Light of life ignites within him.”15

From the war and the loveless embrace of Sulfur and Mercury is born Salt, that is to say the sensible world, the body of man and the body of the world. Nature as seen by separated man is thus nothing other, at bottom, than an immense battlefield strewn with corpses: corpses endlessly “precipitated,” in the chemical sense, by the shock of the two great forces that polarize cosmic psychism. The sensible world in its opacity is then only a “sepulcher” where the soul has buried itself.

We now understand why alchemy is both a “science of balance” and an art of marriages. It elucidates and utilizes the “cosmic sexuality” of Sulfur and Mercury, first “neutralized” in Salt. The alchemist will begin by dissolving these imperfect coagulations and by reducing their matter to the soul: then between the Sun and Moon appearing in their purity the alchemist will arrange a hierogamy that will make them crystallize in a perfect form: gold and the body of glory.

Thus are traced the stages of the work: first the “mortification,” the descent and dissolution in the waters, the disappearance into the womb of the Mother, the Anima Mundi, who devours and kills her Son, that is to say takes back into herself man led astray in the individual condition. This is the domination of Woman over Man,16 of Moon over Sun, until, in the Soul returned to its original virginity, the luminous center, the Spirit, manifests itself. Then is born the regenerated Son, the solar hero: in his turn, he subjects the Moon to the Sun, Woman to Man, and, through the consummation of the “philosophical incest,” he makes of his Mother his Spouse and also his Daughter.

The Mother generates the Son and the Son generates the Mother and kills her.17 One must make the Female mount upon the Male, then the Male upon the Female.18 Once the Little Child has become strong and robust enough to fight against Water and Fire, he will put in his own belly the Mother who had given birth to him.19

These extreme texts introduce us to the phases of the Work.

Throughout this work, we employ the categories of the “science of mental forms” developed in our time by Frithjof Schuon (see notably, by him, Spiritual Perspectives and Human Facts, Paris, Cahiers du Sud, 1953).

It is noteworthy that in Byzantine theology one does not speak of “transubstantiation,” but of “transmutation” of species or “elements.”

Meister Eckhart, Treatises and Sermons, Aubier, p. 211 ff.

ibid.

ibid.

If he had not been so, he could not have transmuted lead into gold, which excluded any use of this power for pleasure and might.

That is to say “incorporating” in terrestrial mode the principles that the planets “incorporate” in celestial mode.

Liber Platonis Quartorum, p.145. Theatrum Chemicum, V.

Henri Corbin, The Tale of Initiation and Hermeticism in Iran, Eranos Jahrbuch, 1949, I, XVII.

We follow here the excellent analysis by Titus Burckhart, Considerations on Alchemy, in Traditional Studies, October-November 1948.

In medieval Christianity, this alchemical doctrine was not based on official theology, whose “creationism” emphasized above all God;s transcendence, but on the lived intuition of the faithful before the “overshadowing” of the Virgin by the Holy Spirit, or on the implications of Genesis reporting that in principio the Ruah hovered over the primordial waters to fertilize them.

The expression is from Jacob Boehme.

Jacob Boehme, Morgenröte, XIII, 55.

The “Kosmou Kore” of the Greek alchemists.

Morgenröte, XXIV, 38.

This applies simultaneously in substances, in man, and in the relations between a man and a woman.

Turba Philosophorum, II, p. 19.

“Book of Synesius,” Library of Chemical Philosophers, II, p. 180.

Flamel, Hieroglyphic Figures, p. 244.