The New Man

Paul Evdokimov

Translated From

Paul Evdokimov. L’amour fou de Dieu. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1973, pp 63-80.

Paul Evdokimov was a notable figure within the Russian émigré community that reshaped Orthodox theology in western Europe following the Russian Revolution. He served in the White Army, and after the Bolshevik victory, he established himself in Paris among fellow exiled Russian intellectuals. During the German occupation of France in the Second World War, he fought with the French Resistance — like many émigré Russians of his epoch, putting his life on the line to fight both of the great collectivist monsters of the 20th century, yet without embitterment or resentment, maintaining an open soul, turned with love to the light of the Gospel and the plight of his fellow men.

Throughout his life in exile, Evdokimov remained faithful to his Russian identity, deliberately choosing to remain a Russian refugee rather than accept French citizenship when offered a prestigious academic position. Yet this faithfulness was accompanied by a profound commitment to building bridges between East and West. Evdokimov devoted himself to communicating the riches of Orthodox spirituality to Western audiences, convinced that its liturgical wisdom, mystical depth, and integrated vision of the human person offered a vital expression of the Gospel that the modern world desperately needed — and he also served as an example of a faithful Orthodox Christian who could appreciate and appropriate the riches of western Christianity, especially in the figures of its great teachers and saints. His writings are filled with warm references to western Christians from Saint Francis to Claudel, Bloy, and Péguy.

His work with ecumenical organizations and his accessible theological writings served as conduits through which western Christians could encounter authentic Orthodox tradition. This dual commitment — to preserving the spiritual heart of Russian culture while opening its treasures to dialogue with the west — profoundly influenced Olivier Clément, who discovered in Evdokimov not just a guardian of tradition but a theological innovator who demonstrated how Orthodox wisdom could speak powerfully to contemporary Western questions about beauty, freedom, and spiritual authenticity.

He wrote numerous books, many of which have been translated into English, including The Ages of Spiritual Life in 1964, and The Art of the Icon, Theology of Beauty, completed in 1967 but published only in 1970.

His son, Fr Michel Evdokimov (1930), also became an Orthodox theologian and priest.

Today, it is no longer merely a question of reforming structures and institutions; rather, it is about giving birth to a new man, a master entirely in control of his destiny and history, clearly convinced of their meaning or absurdity, assuming both equally. It is within this profound tension — where man pushes his rebellion to the point of wishing to remake himself — that the truth of God risks being heard as never before. For its witnesses, its audience sets forth a double demand: on one hand, to be infinitely attentive to rebellious man and his tragic solitude in order to initiate with him a genuine dialogue; and on the other hand, to present the truth in his own language and at his own level. Here, the Word of God, the evangelical kerygma re-heard, will certainly prove more effective than any abstraction derived from a primarily theological system.

Scientific positivism, existentialism, Marxist materialism, or simply common sense — each passionately seeks the new man, the guide, the liberator, who would hold this world in his hands and who would have as keywords: the why and how of human life. We know the evangelical saying: “If the blind lead the blind, both shall fall into the ditch,” below the level of humanity. Thus, it becomes necessary to honestly assess whether today’s aspirations are truly transcendent, and to what they might lead.

The Failure of Atheist Humanism

Human matter, left to its natural means, remains unchanged throughout the centuries, resisting every imposed discipline. “The more things change, the more they remain the same,” says the French proverb. Moreover, there is a formidable regression toward the simius sapiens, the “clever ape,” who advances with the atomic bomb in his hands; this constitutes an unforeseen anthropological transformation, but in reverse. Nietzsche’s “dancing god” risks becoming terribly bogged down in this regressive evolution toward the homo stupidus of doctrinaire ideologies. The insightful philosopher Berdyaev stated irrefutably that God and man, His child, are correlative. “Where there is no God, there is no man either,” such is the outcome of the religion of man.

Man always appears as a divided being, torn by his passions, unreconciled with his own destiny, for he is incapable of giving meaning to his death. The Psalmist knows this (Ps 8:5) and marvels that Someone should remember a creature so miserable. There is no third option. Apart from this divine Someone, Heidegger profoundly emphasizes the tragic solitude of man centered upon cares and death: Sein zum Tode, “being-towards-death.” This is why, according to him, as soon as man tries to transcend himself, he becomes nothing more than an “impotent god.”

Despite the Hegelian and Marxist attempt to assign history a direction that would produce the new man, phenomenology and existentialism have expressed doubts about this man and described him as a broken being, living in a “shattered world.” Thus, the overwhelming mass of his discoveries renders him incapable of constructing a hierarchy of values, or even glimpsing a meaning. An extraordinary abundance of consumer goods is accompanied by a striking poverty of moral and religious sentiment. At the height of his wealth, man no longer knows how he ought to guide and conduct himself. Like a child stuffed with gifts and bogged down in things, man is possessed by his own possessions. But precisely due to abundance, he attaches less value to them. Like his car, no object is intended to be preserved, but exchanged for something better. Nothing is lasting anymore. Thus, the question arises: “Why do I have all these possessions, what shall I do with them?” Troubled and anxious, man interrogates himself — this is even true for an atheist like Merleau-Ponty: “Man is condemned to meaning,” which signifies that his very dignity compels him to find a new vision, one entirely rethought.

The Message of the Gospel

To respond to the world’s questioning, reflection alone is not sufficient. An appeal must be made to the act of faith, to that “renewal of the mind” (1 Cor. 2:16) of which Saint Paul speaks. The conflict between secularized, fragmented ideologies, between isolated individuals, leads nowhere. It calls for a third partner in the dialogue, a Consoler and Advocate, so that “man in his situation” can be seen “with the eyes of God, with the eyes of the dove,” as Saint Gregory of Nyssa says.

The Gospel is very explicit: “I am come a light into the world, that whosoever believeth on me should not abide in darkness” (St John 12:46). And if Christ leaves the world, He leaves behind His Word placed at the heart of history (St John 12:48).1 The Word of life is not a static doctrine, but the living locus of Presence. For this reason, every witness to the Gospel is above all present and actual; he listens to the visible world, but interprets it in the light of the invisible and thus causes the vision of God regarding history and all the legitimate aspirations of modern humanism to converge.

The Witness proclaims to all: the Kingdom of God is among you; God is present in all the events of the world, but you neither know nor perceive it. He challenges people, grasping them in the very depth of their historical situation. He demonstrates the contemporaneity of Jesus and of humanity in every age. It is from within humanism and its values that God addresses the people of the 20th century.

The entire genius of Teilhard de Chardin is to show history of the cosmos as an evolution oriented towards man. If man, certainly, is no longer astronomically at the center of the universe, he is indeed at its summit, for humanity is cosmic evolution become conscious of itself. If the time of the Old Covenant moved toward the Messiah, after Pentecost the time of the Church is oriented towards the eschatological novissima, and carries humanity toward its fulfillment as a new creature, but this time truly new, because it is God Himself who becomes the new Man — ecce Homo, the absolute Man — and all follow Him.

It is not about “patching up,” or “tinkering with” the old man. “The old man is passing away, the new man is renewed day by day,” says Saint Paul (2 Cor 4:16). The metamorphosis of the second birth is radical: “O man, take heed to what you are! Consider your royal dignity!” cries Saint Gregory of Nyssa. “What is man?” asks Saint Paul: “Thou madest him a little lower than the angels; thou crownedst him with glory and honour, and didst set all things under his feet” (Heb 2:7). In the thought of the Church Fathers, in the image of the three dignities of Christ, man is king, priest, and prophet: “King through mastery over his passions, priest by offering his body in sacrifice, prophet by being instructed in the great mysteries.” The great charter of the Gospel joyfully proclaims: “Old things are passed away; behold, all things are become new,” for “if any man be in Christ, he is a new creature” (2 Cor 5:17). Henceforth, what matters is “being a new creature” (Gal 6:15). And Scripture culminates in this testimony of God: “Behold, I make all things new” (Rev 21:5).

In the grandeur of its confessors and martyrs, Christianity is messianic, revolutionary, explosive. The Gospel calls for a violence that seizes the Kingdom and transforms the ancient face of the world into the novissima.

Holiness, A New Dimension of Man

New creature, new man — these terms are synonymous with holiness. “All of you, called to be saints,”2 says Saint Paul. As the salt of the earth and the light of the world, saints are constituted as beacons or guides for humanity. These witnesses, sometimes luminous, sometimes obscure and hidden, fully assume their role in history. “Wounded friends of the Bridegroom,” the martyrs are “ears of wheat which kings have harvested, and the Lord has placed them in the granaries of His Kingdom.” Saints take up the task from the martyrs and illuminate the world. Yet, the call of the Gospel is addressed to every human being, which is why Saint Paul calls every believer “saint.”

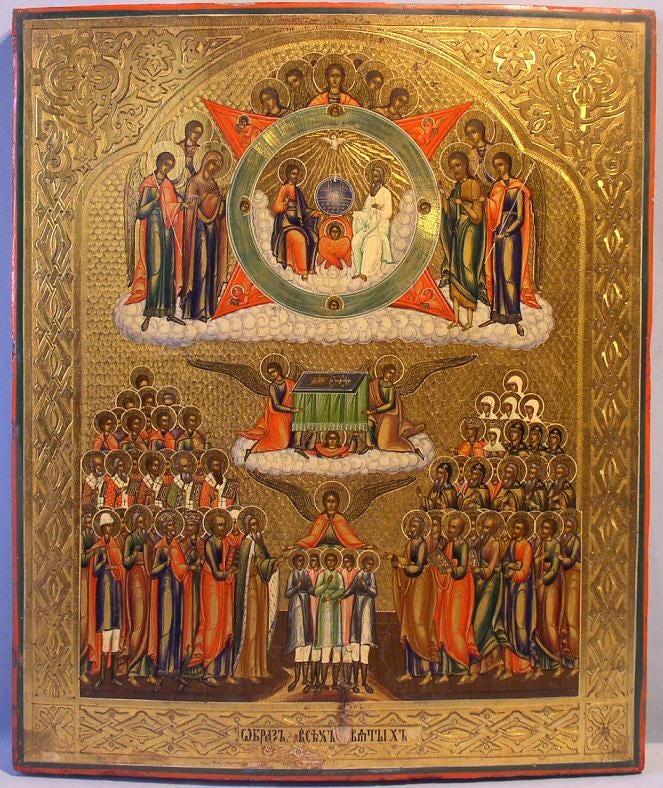

If, since the Incarnation, the Church according to Origen is “full of the Trinity,” since Pentecost it is full of saints. The service of All Saints removes all boundaries: “I sing of all the friends of my Lord, those whom He desires to join Himself to everyone.” The invitation is extended to everyone, “the cloud of witnesses comes to meet us,” says Saint John Chrysostom, to proclaim the invitation urbi et orbi.

Holiness rises up as a characteristic note of the Church: Unam Sanctam. And the communion of saints expresses the holiness of God: “Thy light, O Christ, shineth upon the faces of Thy saints.” But what does holiness mean? If all words designate things of this world, holiness has no reference in the human. Holiness is proper to God. “Holy is his Name,” says Isaiah (57:15). Wisdom, power, and even love have analogies in human life; but holiness is preeminently the “wholly Other.” “Tu solus Sanctus, Thou alone art holy,” (Rev 15:4). Yet, simultaneously, God’s commandment is quite explicit: “Be holy, for I am holy.” Because He is absolute holiness, God makes us holy by enabling us to participate in His holiness (Heb 12:10).

This is the ultimate action of God’s love: “I call you not servants, but friends” (St John 15:14–15). Here lies the very heart of novelty; drawn by the divine magnet, humanity is placed into the orbit of the divine Infinite. God removes humanity from this world and returns it to the world as holy, a receptacle of theophanies and a source of cosmic sanctification.

The Hebrew etymology of the word “holiness,” through its very root, suggests separation, being set apart, total belonging to God, something God reserves, keeps, and destines for a very specific vocation within the world. The Sanctus of Isaiah provokes a sacred fear and accentuates the infinite distance between the transcendent Holy One and the “dust and ashes” of humanity (Genesis 18:27). In the mystery of His Incarnation, God transcends His own transcendence, and His deified humanity becomes “consubstantial,” immanent, and accessible to man — placing him within His own “burning proximity.”

In the Old Testament, theophanies marked certain privileged zones where God appeared with dazzling manifestations: these were “holy places,” such as the “burning bush” (Ex 3:2). But since Pentecost, it is the world itself that is entirety entrusted to the saints in order to expand the “burning bush” to the dimensions of the universe: “for all the earth is my domain,” says God. Formerly man heard: “Put off thy shoes from off thy feet, for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground” (Exodus 3:5); now a fragment of this world is sanctified, because divine holiness has touched it. A very ancient iconographic composition of John the Baptist symbolizes the transition to this new order: the icon shows the Forerunner treading upon ground defiled by sin, a ground of extreme entanglement; yet wherever he passes, the earth beneath his feet again becomes Paradise. The icon signifies: “Earth, become pure again, for the feet that tread upon you are holy.”

A saint, the new man, sharply contrasts with what is habitual, with what is old, and his novelty is scandal and folly. For Marxist praxis, a saint is a useless man — indeed, what could he possibly serve? It is precisely this “uselessness,” or more exactly, this complete availability toward the Transcendent, that raises the essential questions of life or death to a world which forgets them. A saint, even the most isolated and hidden, “clothed with spaciousness and nakedness,” carries upon his fragile shoulders the weight of the world, the night of sin, protecting the world from divine justice. When the world laughs, the saint weeps, attracting upon mankind divine mercy. Such is the hermit, who before dying utters his final prayer as a definitive amen to his entire ministry: “May all be saved, may the whole earth be saved...” Entering into the “communion of sin,” the saints draw all sinners into the “communion of saints.”

What surely scandalizes unbelievers is not the saints, but the profoundly daunting fact that not all Christians are saints. Léon Bloy rightly said: “There is only one sadness, and that is not to be a saint.” And Péguy: “There have always been saints and all sorts of holy women, but now we need a different kind of saint, and we need them even more.” Simone Weil emphasized this need even more strongly, highlighting a particular quality: “The world today needs saints, new saints, saints with genius...”

The Witness

To understand this requirement, we must hear anew the words of Christ as recorded in the Gospel of John (13:20). Christ leaves this world, but He leaves behind the Church; He leaves behind the one sent, who carries on and continues His mission of salvation. He speaks this word, laden with an awe-inspiring meaning: “He that receiveth whomsoever I send receiveth me; and he that receiveth me receiveth him that sent me.”

We see clearly: the destiny of the world — its salvation or its perdition — depends on its attitude toward the Church, which is to say, on its attitude toward Christians. If the world receives one of us, it enters into communion with the One who sends us.

This word is trembling with significance. What kind of presence must we bear so that man may recognize and receive it? How do we fail our own salvation by refusing to be what we are meant to be so that our people may be saved? Our witness, our holiness — are they the presence that brings salvation to man?

Jesus asked His disciples, His friends, to be joyful with a great joy, for which the reasons are beyond man, in the single overwhelming fact that God exists (St John 14:28). It is in this pure joy of selfless love, given entirely and without reserve, that the salvation of the world lies and that the call takes on its new resonance. Not in pragmatism and utilitarianism — “I love you so that I may save you” — but in the purified gesture: “I save you because I love you.” Thus, our creative genius is invited to rediscover the way or the art of being accepted, heard, and received by the world. Saint Paul found it when he said: “It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me” (Gal 2:20). Sermons are no longer enough; the clock of history marks the hour when it is no longer simply a matter of speaking about Christ — it is about becoming Christ, the locus of His presence and of His word.

A Saint For Today

The crowd always seeks “signs and miracles,” but the Lord declares: “They shall have none.” A saint for today is a man like any other, but his very being is a matter of life or death addressed to the world. According to the beautiful words of Tauler: “Some endure martyrdom once by the sword, while others know the martyrdom that crowns them from within, invisibly.” Others still, at the risk of their lives, bear witness today, and their testimony is this silence that speaks.

There are also those who are called to testify before public opinion, before the formidable indifference of the crowd. Kierkegaard said that the first sermon of a priest should also be his last, a scandal so great that he is immediately cast out by the so-called “right-thinking” of society.

There must be saints who know how to scandalize, who embody the foolishness of God in order to make clear the absurdity of, for example, Marxist cosmonauts who were made to search for God and the angels among the galaxies.

A new man is not a superman or a miracle worker. He is stripped of all legend, but he is much more than a legend — he is present, because he is a witness to the Kingdom that already shines forth in him. Yet, the warning of the Gospel remains: “He that hath ears to hear, let him hear!” In contrast to the images of celebrities and the enormous portraits of state leaders exalted everywhere, a saint is a humble man, like all others, but his gaze, his words, and his actions “carry human concerns to heaven and bring the Father’s smile to the earth.”

The Saint and the Nature of the World

Christians “glorify God in their bodies” (1 Cor 6:11–20), says Saint Paul: “Whether therefore ye eat, or drink, or whatsoever ye do, do all to the glory of God” (1 Cor 10:31). Thus, there is an entirely new way of doing things, a way that could be called an “evangelical style” of handling the most ordinary and habitual tasks. A peasant in his field, a scientist studying the structure of the atom — through prayer, their gestures and their gaze are purified, and the matter they touch becomes a “new creation,” made such by the renewed attitude of man, for “the whole creation groaneth” awaiting its liberation in the new man (Rom 8:18-23). The anxious expectation of nature is stretched upward, like the gaze lifted high, or “as the eyes of a servant look unto the hand of his master” (Ps 123:2). Its suffering is not the pain of agony, but that of childbirth.

Christ has destroyed the three barriers: the old nature, sin, and death; He has transformed the obstacle into passage, in Pascha. “He changed death into the slumber of waiting and awakened the living.” The elements of nature retain their appearance, but the saint halts their sterile cycles and directs them toward the purpose assigned to each creature by God. The biblical parable, the māšāl (מָשָׁל), admirably opens us to this new world of God: a sower carries the fragrance of rich, freshly tilled earth; a woman places leaven in the dough; the vine, the fig tree — elsewhere, it is the grain of wheat. The sensible world teaches the deepest mysteries of divine creation.

Liturgy takes up the things of this world and reveals their fulfillment; it performs a de-profanation, a transfiguration within the very being of this world. It pierces its enclosed opacity by the irruption of powers from beyond and teaches that all things are destined for their ultimate liturgical completion. The earth will once again receive the body of the Lord, and the sealing stone of His tomb will be rolled away before the myrrh-bearing women by the angels. The wood of the Cross joins the tree of life; its light always recalls that of the transfigured Lord. The wheat and the vine converge toward their Eucharistic sanctification for “the healing of the soul and the body”; the olive tree will offer the oil of anointing, and water will spring forth the baptisteries for the lavacrum, the regenerating bath of eternal life. Everything refers to the Incarnation, and everything leads back to the Lord. The liturgy integrates the most fundamental actions of life: drinking, eating, washing, speaking, acting, communing, living, dying — finally, in the resurrection, it restores their meaning and their true destiny: to be elements of the cosmic Temple of the glory of God. The Psalms describe a kind of sacred dance where “the mountains skip like rams, and the hills like lambs,” the secret aspiration of all living things to sing to their Creator.

Saint Ambrose warned his catechumens of the danger of despising the sacraments under the pretext of the common nature of the materials used. Divine actions, he explained, are not visible but are “visibly signified.” For the Fathers, the Church is this new paradise where the Holy Spirit raises up “trees of life,” where the sacraments and the mysterious restoration of the saints’ kingship over the cosmos take place. In them, the old nature reaches the threshold of its liberation, and, fertilized by the Spirit, it prepares in its secret germination for the birth of the “new earth” of the Kingdom — just as in the Virgin Mother, it had already given birth to the nature of the second Adam.

The Saint and Men

The Fathers teach that monks are simply those who take the salvation of the world seriously, who follow their faith to its very limits and know that it is capable of moving mountains as the Gospel says. But in their understanding, every believer can become an “interiorized monk” and find the equivalent of monastic vows, exactly in the same way, within the permanent circumstances of his life, whether celibate or married. Thus, his simple yet fully present existence is already a scandal to the conformity of an established world, a testimony that saves from mediocrity and the dullness of ordinary life. In Soviet Russia, a true believer is a burst of God’s laughter, a breath of fresh air in the atmosphere of boredom imposed by fanatical doctrinal ideologues.

A new man is above all a man of prayer, a liturgical being, the Man of the Sanctus — the one who sums up his life in the words of the Psalmist: “I will sing to my God as long as I live.” Recently, in the context of State atheism, the Russian episcopate exhorted the faithful, in the absence of a regular liturgical life, to become temples themselves, to prolong the liturgy in their daily existence, to make their life itself a liturgy, to present a face to those without faith, a liturgical smile, to listen in the silence of the Word in order to make it more powerful than any compromised speech.

Such a liturgical presence sanctifies every fragment of the world, contributing to true peace — the one spoken of in the Gospel. The prayer of this new man rests upon the coming day, upon the earth and its fruits, upon the efforts of the scholar and the labor of every worker. Within the immense cathedral of the universe of God, man, a priest of his world, crafts from all of humanity a great hymn of praise.

Today in Soviet Russia,3 persecutions are intensifying, and in this climate of silence and martyrdom, an astonishing prayer arises, a splendid doxology circulates among the believers, calling upon the Consoler through their abandonment and love:

“Forgive us all, bless us all — the thieves, the Samaritans, those who fall by the roadside and the priests who pass by without stopping, all our neighbors — the oppressors and the victims, those who curse and those who are cursed, those who rebel against You and those who prostrate themselves before Your love. Take us all into Yourself, Holy and Just Father…”

The Fathers of the Church say that every believer is an “apostolic man” in his own way. He is the one whose faith corresponds to the final words of the Gospel according to Saint Mark: “He who walks upon serpents, conquers all disease, moves mountains, and raises the dead — if this is the will of God.” (cf St Mark 16:17-18). Let him live simply, but fully in his faith, let him reach its inevitable fulfillment. Yes! This must be said and repeated constantly: this vocation is not an expression of some mystical romanticism, but of obedience to God, in the most direct and most realistic sense of the Gospel. All these things — just as great as miracles — are born from the purity of our faith, and the call of God, whose power is perfected in weakness, is addressed to each of us. To become the new man is to make an immediate, firm decision of the spirit and of faith — the one who simply, humbly says “yes” to Christ: then everything becomes possible, and miracles happen.

A disposition of collected silence, humility, but also a passionate tenderness. Even the strictest ascetics, like Saint Isaac the Syrian or Saint John Climacus, said that one must love God as one loves his betrothed. For Kierkegaard, “one must read the Bible like a young man reading a letter from his beloved; it is written for me.” It is therefore natural to be in love with all of God’s creation and to decipher, within the apparent absurdities of history, the meaning of God. It is natural to become light, revelation, prophecy.

Astonished by the very existence of God, the new man is also, in a sense, a holy fool like those described by Saint Paul, and it is the striking humor of the “fools for Christ’s sake” that alone can break through the weight of doctrinaire seriousness. As Dostoevsky noted, the world is not in danger of perishing from war, but from boredom, and from a yawn so vast that the devil himself may slip out of it.

The new man is also one whose faith frees him from “the great fear of the 20th century” — the fear of the bomb, the fear of cancer, the fear of death. He is a man whose faith is always a certain way of loving the world, by following the Lord all the way to the descent into hell. God reserves His own logic, which, without contradicting justice, adds a new dimension and requires leaving intact the ultimate mystery of mercy. To be a new man is to be one who, through his entire life and presence, proclaims what is already present within him. To be a new man is also to be like Saint Gregory of Nyssa, full of “sober intoxication,” throwing himself toward every passerby with the words: “Come and drink.” It is also to be one who sings with Saint John Climacus: “My love has wounded my soul, and my heart can no longer suffer Your flames — I go forth singing…”

Christianity, a religion of the absolutely new, is explosive. In the kingdom of Caesar, we are commanded to seek the Kingdom of God, and the Gospel speaks of the violent who seize the heavens. One of the surest signs of the Kingdom’s approach is the unity of the Christian world. It is the ardent desire, the ardent prayer, the ardent violence — as spoken of by Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras during their providential meeting in Jerusalem in January 1964. We must meditate on their words concerning “fraternal charity, ingeniously finding new ways to manifest itself,” for the Christian world has lived through the dark night of separation, and “the eyes of Christians are weary of gazing into the night.” The miracle comes from God alone, but it is suspended upon our transparent sincerity, upon the purity of our hearts.

The image of all perfections, Jesus Christ is the one supreme Bishop, and He is also the one supreme layman, the new man par excellence, the Saint. That is why His sacerdotal prayer carries the desire of all the saints: to glorify the Trinity with a single heart and a single soul and to unite all men around the one and only Eucharistic Chalice. Divine philanthropy awaits us, to share with us a joy that is no longer of this world alone, a joy that inaugurates the banquet of the Kingdom. At the heart of existence is the radical encounter with the One who already comes; Man finally becomes what he truly is, as divine eternity transforms him. Having arrived at the threshold of ultimate desire, nothing remains but to repeat the magnificent words of Evagrius, who describes the new man as: “the man of the Eighth Day”:

He is separated from all, and united to all;

Impassible, and of a sovereign sensitivity;

Deified, and he considers himself the refuse of the world.

Above all, he is happy,

Divinely happy...4

“He that rejecteth me, and receiveth not my words, hath one that judgeth him: the word that I have spoken, the same shall judge him in the last day.”

cf Romans 1:7

This essay was written before Evdokimov’s death in 1970, and published in 1973. The text in which it was published does not indicate the date of its composition.

I. Hausherr, Les Leçons d’un contemplatif. Le Traité d’oraison d’Évagre le Pontique, Paris, 1960, p. 187.