The New Theology: Parts Two and Three

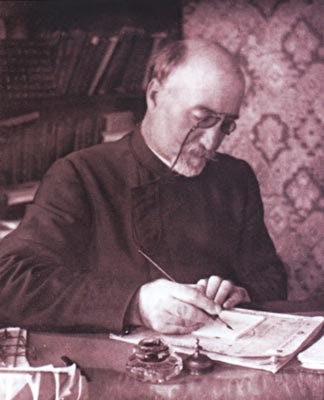

Mikhail Mikhailovich Tareev

Part II

The idea of two methods in the construction of a science — the objective-abstract method and the moral-subjective method — has already been expressed in the philosophical methodology of the sciences. I will mention the most well-known names. These are Dilthey1, Wundt2, and Münsterberg3 and other proponents of the Marburg school (Cohen, Natorp, and especially Stammler), who divide the entire scope of scientific knowledge into two groups of sciences based on content — sciences of nature (Naturwissenschaften) and sciences of the mind (Geisteswissenschaften); Windelband4 and Rickert5, who differentiate between two groups of sciences based on method — sciences of nature and sciences of culture; and our sociologists Lavrov, Mikhailovsky, and Professor [N.I.] Kareev — the so-called Russian subjective sociology.

All these authors contrast the natural sciences, as sciences of concrete reality, with the social sciences and history, and introduce the principle of moral-subjective evaluation into the socio-historical sciences. Familiarity with their theories is very useful for theologians, especially for moralists. Nevertheless, in these theories, the concern is with the method of historical science, rather than with the method of spiritual science, which stands in contrast to the natural sciences. The morality applied in them to the construction of socio-historical science — ethics, as Cohen expresses it, being the logic of the sciences of the spirit — is a conditional social morality. The terminology of Münsterberg, which distinguishes between objectivizing and subjectivizing approaches to scientific knowledge, must be recognized as less fortunate than the terminology of Rickert, who assigns the method of generalizing (generalisierende Auffassung) to natural science and the method of individualizing (individualisierende Auffassung) to history. Likewise, Rickert’s theory of historical knowledge is more sound in that he finds it possible to apply to historical development not a moral evaluation (Wertung), but only an attribution to historically recognized values (Wertbeziehung). In the full sense, the moral-subjective method of knowledge can be a method of spiritual science, applicable to the understanding of spiritual truth.

Since the time of Auguste Comte, who divided sociology into statics and dynamics, it has become widely accepted to distinguish between static and dynamic perspectives in the science of human beings. In particular, this distinction between methods of systematizing material has become firmly established in the philosophy of law. Here, two orders of legal evaluation are recognized: the static-dogmatic and the dynamic-teleological. (See, for example, A. L. Baikov’s The Legal Significance of the Clause “Rebus Sic Stantibus” in Intergovernmental Relations, 1916). From this, the philosophy of law is divided into two parts: the statics and the dynamics of legal relations. Professor I. V. Mikhailovsky, in his book Essays on the Philosophy of Law, Vol. I (1914), begins the section on The Dynamics of Legal Relations with the following words: “Up until now, we have studied legal relations in a state of rest, their statics. But concrete legal relations are in continuous motion, reflecting the movement of life. They arise, change, cease; various rights are violated in one way or another, defended in one way or another. What remains for us is to examine the causes, conditions, and forms of the movement of legal relations, their dynamics” (p. 572). Applying this methodology to theology, we clarify the mutual relationship between dogmatic theology and the moral doctrine of Christianity: dogmatics is static theology, while the moral doctrine is dynamic theology. The theological methods we have outlined — dogmatic-objective and moral-subjective — can also be called dogmatic-static and moral-dynamic, or subjective-dynamic. Dogmatics deals with the abstract formula of Christianity, while the moral-subjective doctrine understands Christianity in its living mobility, its vibrant rhythm, and its concrete dialectic.

Part III

As sciences, dogmatic theology and the moral doctrine of Christianity are equal in rights, value, and consistency. However, the moral doctrine of Christianity, while appearing as a specialized science, specifically as the doctrine of Christian life, almost imperceptibly passes into Christian philosophy. In other words, the moral doctrine of Christianity, as the science of Christian life, is separated from Christian philosophy by an imperceptible boundary: Christian philosophy is the highest form of the moral doctrine of Christianity. I also want to emphasize that the science of Christian life reaches its full completion only within the expanse of Christian philosophy. It has an inevitable tendency to transform into a system of Christian philosophy. It is the only theological science for which a philosophical formulation, a system, and creativity are necessary. Furthermore, Christian philosophy, as a system of religious thought, is only able to strengthen its roots in the science of Christian life. It can only be constructed by the moral-subjective method, and can only exist as a creatively subjective system. (Strictly speaking, the moral doctrine of Christianity as a science cannot exist independently, but rather as the starting point of Christian philosophy — its foundation, its support, its scientific form, distinguishing “scientific” Christian philosophy from an unscientific and ignorant, though perhaps deeply heartfelt and poetic, Christian worldview. In this sense, the science of Christian life does not stand alone but functions as an application of other theological sciences, primarily Biblical theology.) In the open field of Christian philosophy, the moral teaching of Christianity holds distinct advantages over dogmatic theology.

Dogmatic theology, being a science, as the historical doctrine of dogmas, can take the form of philosophy. And what is specifically “Christian philosophy,” not as philosophy that is Christian in content, but as Christian philosophizing — this is dogmatic theology. Just as Christian dogmas represent the expression of Christian truth in the terms of pagan philosophy, so too does dogmatic philosophy operate entirely with philosophical concepts — those of epistemology, ontology, and principally metaphysics. And if the moral doctrine of Christianity must be constructed in the form of Christian philosophy, then dogmatic theology has a natural-psychological inclination towards “philosophy,” towards abstraction. It should also be noted that the old theology did not recognize dogmatics as a science — i.e., a science of dogmas; for it, dogmatics was a dogmatic system, and it equated the theological system with the dogmatic system. Even with the introduction of “practical theology” into the circle of theological sciences, dogmatics was still considered the only theological science, the only form of theological knowledge, while moral theology alongside it was not considered a theological science but merely an applied discipline. From the Christian, both knowledge and faith are required on the one hand, and a good life on the other. Theological knowledge is offered in dogmatics, while moral theology teaches how to live a good life, instructs, edifies, and admonishes. Theological science is dogmatics, and the theological system is the dogmatic system — such was the principle of the old theology.

The old theology represented the worst kind of Christian “philosophy.” If it did not recognize dogmatic science as the historical doctrine of dogmas, it also did not recognize “philosophy.” It distinguished neither science nor “philosophy” and was a single, undivided scholasticism. In it, there was neither theological science nor religious-philosophical creativity.

By identifying the theological system and theological science with dogmatics, the old theology made the task of dogmatics the immersion of the dogmatist into the current of dogmatic definitions of faith, the comprehension of the dogma through reason, the assimilation of dogmatic thought, and the merging with it of the inquisitive, probing mind. This is how the theologian viewed his work:

“Any Orthodox work on the dogmas of faith and, in general, on positive truths, must inevitably draw its material from the Holy Scriptures and the writings of the Fathers or, more broadly, from the Tradition of the Church. The writer’s merit lies here, in how skillfully he uses this rich material, in how well he is able to extract the necessary evidence from the given sources, assimilate it, and handle it as if it were his own property; combine and arrange it according to a given idea; unify, enliven, supplement it with his own reflections and explanations; and present it in his work as a coherent whole. This is how Orthodox theological systems and specialized theological studies are written, and no one calls them unoriginal simply because the main, fundamental content consists of Biblical texts and testimonies from the Fathers of the Church.”6

The idea of the dogmatic formula here provided the entire foundation for the theological construction. The theologian made no attempt whatsoever to objectively investigate this idea, nor did he contribute anything new or creative to its content; he had no foundation within himself for re-presenting it. For him, the only possibility was its logical assimilation and explanation, that is, the systematic, logically structured exposition of its proofs, clarifications, apologetics, and so forth. The basic premise of such theology was, to varying degrees, a positive resolution of the question concerning the relationship between reason and revelation. Nevertheless, the problem of the role and competence of reason in theology remained one of the most difficult, if not unsolvable, challenges. The participation of reason in theology, without which there would be no place for theological science itself, was nothing other than its participation in dogmatic teaching, which bore the authority of divine revelation; however, the involvement of reason in divinely revealed teaching can only be affirmed with the utmost caution. Without the use of reason, theological science would be impossible; reason is necessary for the assimilation of revealed truth, but revealed truth is entirely given for reason, and it surpasses its capacities.

“What should the relationship of reason be to divinely revealed theoretical teaching, and in what does its development in relation to the latter consist? It is said that revealed truths cannot be the subject of scientific proofs, since they must be assimilated by faith and are objects of faith, and the realm of faith, it is argued, is entirely different from the realm of scientific knowledge: faith excludes any involvement of rational activity and belongs only to the emotions, not to the mind, to which knowledge belongs. On the other hand, revealed theoretical truths, which form the content of theological science, are eternal, unchanging, and incomprehensible truths; therefore, there can be no place here for the scientific and free activity of reason, and thus, it is argued, theology as a science is impossible. The latter is enriched every year with new discoveries and acquisitions, while Christian truths remain the same, merely repeated in different forms. What is to be said about such judgments?”7

These very questions, which the old scholastic theology asked itself, are characteristic; in them, the entire rationalist framing of theology is predetermined. And what did the theologian answer to these questions? He agreed that theology could be neither a science nor a philosophy.

“Whereas every science, with regard to its method, begins with analysis and ascends to synthetic truths as the sought-after result, found through analytical means, theology follows the exact opposite path: it accepts and must accept ready-made truths given in revelation as its starting point, the content of which it must subsequently elucidate through analysis. Furthermore, while in science it is possible to progressively discover new unknown truths through the known ones, in theology this is entirely impossible, as its content is immutable and given once and for all: there were and are no new discoveries in it, and there can be no invention of new truths unknown to mankind. Theology cannot be a scientific philosophical system either, because the latter still searches for truth and in its investigations is guided by the unstable considerations of the mind and does not know the limits of its curiosity.”8

The role of theology is much more modest compared to science and philosophy; its task is unique.

“Nevertheless, progress or development is possible even in theology, but only a distinctive development, unlike the development of all other sciences... It is true that the revealed truths, which are the subject of theological science, are immutable in content and seemingly exclude any activity of reason with regard to them, because they are not the products or thoughts of the human mind, but are revealed by God Himself and are, so to speak, the thoughts of the divine mind, with which a person cannot deal according to his own personal will and judgment; nevertheless, it is impossible not to recognize in them another side, subject to the activity of our reason. Although immutable and perfect in their content, revealed truths can and must have a certain type of development and perfectibility; this perfectibility does not consist in changing the content of revealed truths or in inventing new doctrines to replace them, but in clarifying their meaning, in the unfolding and understanding of them by our reason. In other words, the truths of Christianity themselves are unchangeable, but in terms of human consciousness, they change and perfect themselves, or, more precisely, it is not the truths of Christianity themselves that change, but our assimilation and understanding of them. Progress is possible in theology, although of a unique kind — not in relation to the content of its subject (reason cannot discover any new dogma), but in relation to the unfolding and assimilation of this subject by the human mind. This is the basis of the possibility of theological science; the latter cannot be limited to merely repeating Christian church doctrine, which is to serve only as its material, but must engage in the analysis and elaboration of it, framing it in various ways according to established scientific techniques and methods. And in this regard, reason must show its broad involvement: first, by its own activity, it must, as deeply as possible, clarify the meaning of the dogmas, placing them in harmonious relation to scientific concepts and perspectives; moreover, the activity of reason must and should also manifest itself in refuting various objections to Christian dogmas. Secondly, reason must clothe Christian conceptual truths in a clear and comprehensible form, as much as possible, expressing them in a more understandable and lucid language; it must also demonstrate their great significance and internal coherence, and the extraordinary logical consistency of the entire system of revealed teaching.”9

Such is abstract theology — this dogmatic philosophy. It is pitiful and barren, lacking both deep roots and broad perspectives. It is solely the work of a mind whose wings have been clipped. Theology approaches the dogmas with the strength of the intellect alone, but they are incomprehensible to the mind. What remains for theology is secondary work: it is a gatekeeper, for whom the sanctuary of Truth is inaccessible. This is the theology that rightfully bears the deserved contempt of representatives of science and philosophy.

In the new theology, everything is approached differently; it embarks on a completely new path, finally overcoming the old scholasticism. It strictly distinguishes between science and philosophy, pursuing two distinct goals — scientific and philosophical.

Theology is, above all, a science in the strict sense of the word. For a long time now, the fundamental, or elementary, theological branches — Scriptural studies (Biblical theology) and the study of Tradition (church history) — have taken on a fully scientific character within the broad field of theology. In recent times, the scientific method has also been applied to the field of systematic, or better said, positive theology. From this new perspective, dogmatics is nothing other than the science of dogmas. Here, the fact to be scientifically and theologically investigated is the dogmatic formula. Dogmatics must be a science of the dogmatic formula, a historical-philological study of it.

“The task of scientific-critical dogmatics is (1) to define, with the greatest possible precision, the boundaries of the dogmatic, i.e., the Church-mandated content of the faith, specifically: (a) to enumerate everything that is Church-mandated (in terms of doctrine) and (b) to mark the limit to which each dogma and the entire dogmatic realm extends — and (2) to establish as clearly as possible the meaning of dogmatic formulas. More specifically, scientific dogmatics must determine the sources of church dogmas and restore the historical-philological genesis of dogmatic terms. Restraint from any interpretation of the dogmas, from introducing into the system anything subjective (personal opinions) or disputable, anything designed to satisfy curiosity or a Gnostic itch, is implied as a merit of such a dogmatic system.”10

It is evident that with such tasks, dogmatics has the potential to be fully scientific, and indeed, such tasks can only be solved by scientific means. The question of the mutual relationship between revelation and reason, the participation of reason in dogmatic creation, and the competence of reason in the knowledge of God has no direct bearing on the scientific work of the dogmatist. He in no way participates in dogmatic creation; for him, the given dogmatic formula is a complete fact, which he studies from a scientific, historical-philosophical, and philological standpoint. One must strictly distinguish between essential theology and technical theology. Essential theology is the word or teaching about God, and such a word about God can only be God’s own word: God’s word about God. Scientific theology does not coincide with this essential theology and bears none of its characteristics: it is merely the science of theology. Likewise, “dogmatic theology” is that theology which is contained in the dogmas: the Creed is dogmatic theology proper, but dogmatics is not dogmatic theology, it is only the science of dogmatic theology — and that in the fullest sense.

Theology is a science in which reason is subject to no other limits than those that exist for reason in any science. It is fully competent here; it formulates the questions, and these questions can only be solved by its means. How does the Church teach on this or that point, and how does this or that Church Father teach? When was this or that dogma formulated, from which philosophy were its terms borrowed, what did they signify there, and in what sense were they incorporated into the dogmatic formula? All these are purely scientific questions, and scientific dogmatics must not step outside their scope, but within their boundaries, it is fully competent. Thus, theological science is primarily dogmatics, that is, the study of dogmas, the science of dogmatic theology. We have already seen that scientific theology is not exhausted by dogmatics: it is also the science of Christian life, known as moral theology. Moral theology must be the science of Christian life — both personal (spiritual) and ecclesial. It is nothing other than a science. It is not its task to teach Christian morality, to preach, or to cultivate Christian living; its task is simply to provide the teaching on Christian life. Positive theological science is the study of dogmas and the study of Christian life. But of these two teachings, the most typical for theological science is dogmatics, which is fully in line with the fact that dogmatics is, in reality, the most developed, whereas moral theology is a science not yet established. One can confidently say that positive theological science is dogmatics proper, that is, the science of dogmas.

The concept of theology as a science, of theological science, postulates a new realm of theological thought — Christian philosophy. Theological science, not only in the form of the study of Scripture and the study of Tradition (Church history), but also in the form of positive theology as the science of dogmas (and the science of Christian life), does not have a constructive or creative nature; it does not yet provide a Christian worldview or a Christian understanding of life — it is, by its very nature, entirely objective. Risking being misunderstood, we might say: the science of Christian dogmas can be taught, just as as can Church history, even by an unbelieving scholar. Constantine the Great discussed the concept of consubstantiality (ὁμοούσιος) with the Fathers of the Council of Nicaea without even being a catechumen. Or, at the very least, we can put it this way: in theological science, in the strict sense of the word, faith should not manifest its creative power; there should be no place for anything subjective in it. The full creative potential of personal faith cannot be revealed within it, and it cannot satisfy all the needs of a believing heart.

For all of this, the place is not in theological science, but in Christian philosophy, which must be set apart from science and built by its own method. Christian philosophy, as a system of religious thought, must be the reason of Christian experience, the dialectic of the Christian spirit, and it is built solely by a subjective method, representing a clearly personal religious thought. Christian philosophy is entirely the fruit of the believing mind and the evaluating heart, not the work of logic or discursive thinking; therefore, it has the closest affinity with the moral doctrine of Christianity as the science of Christian experience, of Christian life.

The full creative potential of personal faith cannot be revealed within [theological science], and it cannot satisfy all the needs of a believing heart. For all of this, the place is not in theological science, but in Christian philosophy, which must be set apart from science and built by its own method.

In contrast to the old rationalistic theology, Christian philosophy is the least in step with Gnostic quests, and is not at all limited by the confines of human knowledge. Just as in the scientific realm of the new theology, the old scholasticism is overcome, so are rationalism and Gnosticism overcome in the philosophical part of new theology, in Christian philosophy.

While grounded in theological science and scientific in this sense, Christian philosophy is no longer theological science: it deals with Christian experience, which it processes and systematizes using its own distinct, subjective method. The result of Christian philosophy is not universally binding rational truth or logical construction, but a subjective understanding of life, which responds to the needs of one’s own heart and intimately influences minds, seeking like-minded hearts and uniting kindred souls. Unlike the old rationalism, Christian philosophy, scientific in its foundation and subjective in its method, deals not with divinely revealed abstract and intellectual truth, which demands faith and is accessible to reason only in a formal sense, but with the content of the dogma, with the mystical experience that fills its formula. In relation to his own experience, in the matter of its systematization, the Christian philosopher is an unrestricted master. He branches off from the historically given trunk, tastes of the one Christ shared by all, but perceives Him personally, walking his own path to Him. Objectively, dogmatically, Christ is understood in unison by all the members of the Church, but experientially, He is apprehended in countless ways. The Christian philosopher takes root in the depths of his own experience. He is not only free from the necessity to repeat the old, nor is he merely able to diversify universally binding formulas with personal opinions; no, relying on personal, unrepeatable experience, he can bring forth a new word, illuminate Christianity from a completely new angle — and not only can he, but he must, for in the novelty of experience and the originality of religious thought lies the sole foundation for the emergence of a system of Christian philosophy. And there is no limit to original creativity in this area, for there is no limit to the diversity of personal experiences.

The result of Christian philosophy is not universally binding rational truth or logical construction, but a subjective understanding of life, which responds to the needs of one’s own heart and intimately influences minds, seeking like-minded hearts and uniting kindred souls… In relation to his own experience, in the matter of its systematization, the Christian philosopher is an unrestricted master. He branches off from the historically given trunk, tastes of the one Christ shared by all, but perceives Him personally, walking his own path to Him.

It is enough to compare the scholastic system of dogmatic philosophy with the idea of the new theology in its two parts — theological science and Christian philosophy —to see all the poverty of the scholastic system and the superiority of Christian philosophy over the old dogmatic (theoretical) philosophy. But even if we imagine dogmatic, or theoretical, philosophy in its possible purity, free from the old scholastic methods of thought, it still cannot be Christian philosophy. Christian philosophy, as a discipline distinct from specialized theological sciences, must be unified across all aspects of Christian thought and comprehensive. Meanwhile, the dogmatic, speculative system cannot have such a comprehensive significance. Specifically, it does not encompass moral-spiritual experience.

A theological system which centers on dogmatics and is oriented toward dogmatic theology recognizes moral theology as a practical-applied discipline. But as a practical-applied discipline, moral theology does not even deserve the title of a science. Hence the contempt it receives from theologians of the old school. Even in 1900, Professor P. I. Gorsky-Platonov wrote: “Moral theology, pastoral theology, are only called sciences by tradition passed down from the Middle Ages (?), even though these so-called sciences have no scientific content whatsoever. They haven’t even managed to come up with a satisfactory name for themselves. In fact, what is theologia moralis, theologia pastoralis? Certainly not a moral teaching about God, not a pastoral teaching about God, but rather God’s teaching about morality, God’s teaching about pastoral care. So, where or how does the concept of science fit in here? Read the Ten Commandments, read the Sermon on the Mount by the Savior, or: read the pastoral letters of the Apostle Paul, read Chrysostom. And then what? After that, just dive into eloquence, rhetoric, and idle talk as far as your talent and inclination allow.”11

Gorsky-Platonov and theologians like him did not realize that they themselves were responsible for the low status of moral theology, that the proverb “who the hat fits, let him wear it” applied perfectly to them in this case: they could only accept moral theology in such a pitiful form because they could not conceive of any other possibility beyond theoretical knowledge. They could only accept moral theology in such a miserable form because they did not suspect the possibility of another, more-than-theoretical, spiritual-experiential knowledge of the Christian Truth, which is realized in a discipline of science and philosophy, independent of dogmatics.

In a theological system built under the dogmatically objective angle of view, under the dominance of dogmatics, there is, strictly speaking, no place for moral theology as the science of Christian experience, or even as a practical-applied discipline. Dogma is the church-mandated belief; in practice, it corresponds to church-mandated rules of conduct, which define liturgical and canonical Church praxis. In the dogmatic system, the practical-applied disciplines are canon law and liturgics: where is there room for moral teaching, for the science of Christian experience? Naturally, in the old theology, moral theology ended up being a stillborn child. Professor S. S. Glagolev, in his article On Theology, first published in the Orthodox Theological Encyclopedia (edited by Lopukhin) vol. II (1901) and later reprinted in the book A Guide to the Study of Basic Theology (1912), had the courage to acknowledge this state of affairs.

Professor S. S. Glagolev belongs entirely to the old theology, but his article stands out favorably in the literature of that school for its consistency of thought. He divides theology into theoretical and practical. Theoretical theology is dogmatics. Dogmatics also includes the elaboration of religious-moral truths, so moral theology is a branch of dogmatic theology that has grown to the size of an independent science. Moral theology is part of the unified theoretical theology, but it is not “practical theology, which teaches how to live according to faith and how to lead others to faith. These are the tasks of the applied theological sciences, among which moral theology has no place... The theoretical theology speaks of religious-moral commandments, but it is practical theology that teaches how to implement them. The former provides general formulas, the latter shows how to apply them to specific cases. The commandment Love your neighbor as yourself is a formula, but the set of rules on how to instruct a Russian peasant in the truths of faith and morality — i.e., how to express your love for him in the best possible way — is practical guidance. Love for one’s neighbor is expressed in prayer, and in a religious community, it must be expressed in communal prayer. The rules on how to organize prayer or liturgical gatherings, shaped by historical circumstances, are practical rules. There can be many applied practical sciences. Among the most important are liturgics and canon law. Practical theological sciences include pastoral theology, catechetics, homiletics, and ascetic praxis. All practical sciences find their starting principles in theoretical theology.”

Thus, the circle of theological sciences is divided into two sections: theoretical theology — dogmatics, which may or may not include moral theology, as it can fulfill its task on its own, and applied practical sciences, among which moral theology has no place.

In the dogmatic system, there is no place for moral teaching. This means that dogmatic philosophy, constructed by the objective method, has no access to spiritual life, to Christian experience, which remains elusive for it. It has no place for that which is most precious and profound in Christianity, which constitutes the very Christian life, shapes the Christian personality, and is the spirit and essence of Christianity — the very thing for which the human heart longs and through which the Christian religion enlivens and nourishes the human soul. I have always been amazed by the official structure of theological sciences: everything is accounted for, everything is divided among individual professors, each of whom knows his niche and none of whom interferes in the sphere of another. But what has been forgotten, and what no discipline or professor has been assigned, is the most important thing — the one and indivisible thing. Christianity itself, as a precious pearl, as the highest treasure in the world, has been forgotten, along with its own “hidden” content — its soul. Let a believing Christian enter the seminary, already instructed and nurtured by experienced pastors and spiritual elders, desiring to illuminate his faith, his spiritual life, with the light of science and to understand it with theological reasoning. Where, to which of the theological sciences, should he turn?

What has been forgotten, and what no discipline or professor has been assigned, is the most important thing — the one and indivisible thing. Christianity itself, as a precious pearl, as the highest treasure in the world, has been forgotten, along with its own “hidden” content — its soul.

“I would like to know what happens between Christ and the soul, about the true, genuine Christian Truth, about its sweetness, its reason, and its meaning.”

The dogmatist will not respond to his request. His task is to formulate Christianity in the terms of philosophy: ονσια (essence), φυσις (nature), ϑελημα (will). He teaches about what existed when there was nothing, what happens in Heaven, and what will occur beyond the grave. As for what happens in the Christian soul, here on earth, now — he has no terms, no words for that. His language is completely unsuited for such topics. Would you care to argue about transubstantiation or the two natures?

“I’m not interested in that.”

Moral theology teaches about duties, virtues, and vices. “The Christian’s duties toward God. Sins against faith: superstition, coldness and indifference toward faith, doubt and skepticism, apostasy, unbelief. The Christian’s duties toward himself...” All of this is too superficial, fragmented, and mechanical. Not a word about freedom and spirit, about the Christian meaning of life, or about the essence of the Christian idea.

Liturgics, canon law...

There is no science of Christianity among the many sciences into which theology is divided. Such a science can only be the moral-subjective teaching on Christianity, Christian philosophy.

While the dogmatic system of theology does not encompass the content of Christian philosophy — that which is most important in Christianity — Christian philosophy, on the contrary, does not exclude dogmatic theology, and indeed, gives it its rightful place.

Christian philosophy is composed using a subjective method; it deals with the intimate aspect of Christian facts, with their internal value and meaning. But this does not mean that its conclusions cannot be expressed objectively. The relationship between subjective and objective knowledge is akin to the relationship between causal and teleological orders, which are mutually reversible. Any thesis of subjective understanding can be translated into the language of objective knowledge. This is possible and psychologically natural, just as we continue to see the sun moving across the sky even after learning that the earth rotates. The objective expression of spiritual-experiential knowledge, of mystical understanding, is in many respects also expedient.

Spiritual experience can only be made universally comprehensible by giving it a theoretical, abstract form. Therefore, public teaching and catechesis cannot do without an objective system. Dogmatics is specifically school theology. It provides space for proofs, and apologetic and polemic theology are associated with it. Thus, subjective-mystical knowledge is clothed in rational concepts. Insisting on the originality of subjective-mystical inquiry, we do not deny the necessity or usefulness of rational methods of thought. However, we have the right to wish that the rational expression of religious thought be applied consciously, with a clear awareness of its limits and purposes. Objective-rational concepts in a religious system of thought are permissible only insofar as they embrace religious experience, encompass mystical content, and remain connected to spiritual reality, as long as they do not begin to live an illusory independent life.

The subjective-mystical orientation of Christian philosophy does not exclude the use of objective-rational concepts — it is simply not compatible with rationalism or objectivism. It merely disallows reason from being considered as the source of religious knowledge independently of spiritual-mystical experience; or, in other words, it does not permit the religious system to cater to human curiosity. Anyone who has tasted the sweetness of spiritual knowledge can no longer find interest in Gnostic theorizing. Just as the laboratory, while breaking water down into its elements, does not interfere with the practical use of water in life, and is content with its own scientific goals, so too does spiritual philosophy refrain from meddling with the social application of objective-rational concepts. In its exclusive domain, spiritual philosophy retains the hidden depths of religious knowledge, the inner content of rational religious concepts.

The difference between the rational-objective system of Christian philosophy and its subjective-mystical orientation is established not at the surface level of practical achievements within the church community, but in the depths of the selfless demands of the individual heart. Christian philosophy is not needed for the immediate goals of public catechesis or school instruction; it becomes necessary when there is a need to review established concepts and norms, to reform contemporary religious consciousness, to renew stagnant customs, and to fundamentally restructure the spiritual edifice. It is necessary when one must descend into the hidden laboratory of the spirit, where spiritual values are first defined, into that underground depth where the very roots of the spiritual tree originate.

This depth is where the disinterested yet vital demand of the believer’s heart leads, and in this laboratory, the free spirit of the Christian is the ruler, creator, uncompromising legislator, and judge. Whoever has managed to descend into this depth, to visit this laboratory of spiritual values, can then apply rational-objective formulas with full awareness of their subordinate role. In contrast, objectivism, as a system of religious thought, does not remain confined to the utilitarian role of objective religious concepts — it unconsciously transgresses the boundary established by their subordinate character, satisfying Gnostic cravings and excited curiosity. This is the point where one must choose between the objective system of religious thought and the moral-subjective (mystically-subjective) system of Christian philosophy. It is a choice between a barren, albeit self-serving, Gnosticism — a philosophy of bad taste — and the highly productive, intimately perceptive, spiritually rich philosophy that, though selfless in its motives, is abundant in inner content and ripe with results. Meanwhile, the intermediate element — the rational-objective expression of spiritual experience — remains psychologically inevitable and appropriate for the purposes of public catechesis and school instruction.

Even more can be said about the relationship between dogmatic theology and Christian philosophy. What are dogmas? They are beliefs, fixed and elevated to the level of obligatory tenets by the Church. Yet beliefs naturally arise from the soil of spiritual experience. Spiritual experience is the living recognition of religious, absolute values through faith. A spiritual value, which is in itself indisputable for the believing heart, raises a series of questions for the Christian mind that collectively form religious metaphysics. These questions include: “What is the pre-worldly origin of these values? What is their transcendent fate?” Whoever believes in the absolute value of the spiritual Good, who recognizes Christ as God, cannot help but believe and hope that God’s omniscience and omnipotence guarantee the preservation of this spiritual Good amidst the conflict of worldly forces, and its transcendent significance. Christian experience, guided by faith, serves as the source from which a whole array of belief-hypotheses emerge, each particular to the individual in whom they arise. The Church elevates some of these beliefs to the status of universally binding dogmas. These belief-dogmas have significant practical importance: they generate motives for the Christian’s fidelity to the spiritual Good.

The explanation of human history through the Fall and Redemption, the hope in God’s grace, the expectation of posthumous rewards for the righteous and punishments for sinners, the anticipation of a new heaven and a new earth where God’s righteousness dwells — all these strengthen the Christian’s loyalty to his calling. This is the moral significance of dogmas, or the dogmatic foundation of Christian morality. However important this may be practically, and however abundant the psychological dynamics surrounding dogmas in church history may be — vividly manifested in church art — the moral significance of dogmas is not high in principle.

According to the explanations of the holy Fathers and more recent authoritative theologians, motives should not play a significant role in the life of a Christian. They are useful in the early stages of spiritual growth, but the perfected Christian must do good out of selfless love for God. Much more important is the connection between belief-dogmas and spiritual experience in another sense — the emergence of the belief-dogmas themselves from the depths of spiritual experience, which can be called the moral or mystical foundation of dogmas. The belief-dogmas themselves grow from the soil of spiritual reality; they are postulated by it. They are determined by the content of spiritual reality. As a person is, as their faith is, so are their beliefs and expectations, so are their religious concepts. These are branches that appear on the trunk of Christian life. The reciprocal influence of belief-dogmas on life does not prevent them from having spiritual experience as their root, and this is the most essential aspect of the relationship between beliefs and life. Beliefs are necessary for spiritual life, just as an army is necessary for a state; they strengthen and protect faith. But just as the army should not govern the state, beliefs should correspond to the spiritual Good, stand at its level, be useful for spiritual growth, be nourished by the sap of spiritual reality, never severed from it, and forever renewed by its content. Christian philosophy, as the dialectic of spiritual experience, cannot help but value belief-dogmas, and provides them with the deepest justification. Yet it remains independent of dogmatics, for it grows from what precedes beliefs. It delves deeper than the layer to which beliefs belong. While dogmas create motives for a good life, which are of secondary importance, Christian philosophy deals with the very roots of dogmatic theology, the origins of beliefs.

Beliefs are necessary for spiritual life, just as an army is necessary for a state; they strengthen and protect faith. But just as the army should not govern the state, beliefs should correspond to the spiritual Good, stand at its level, be useful for spiritual growth, be nourished by the sap of spiritual reality, never severed from it, and forever renewed by its content.

The highest stage of the moral doctrine of Christianity is Christian philosophy. It is this Christian philosophy, which emerges from the moral doctrine of Christianity and shapes spiritual and mystical experience — rather than a dogmatic system — that is the true system of Christian thought in terms of creativity, depth, and comprehensiveness.

It is Christian philosophy that I am placing, secondly, in place of the old moral theology.

Einleitung in die Geisteswissenschaften: Versuch einer Grundlegung für das Studium der Gesellschaft und der Geschichte; Studien zur Grundlegung der Geisteswissenschaften in Sitzungsberichte der königlich-prenssischen Akademie der Wissenschaften; Der Aufbau der geschichtlichen Welt in den Geisteswissenschaften in Abhandlungen der Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften

Logik: Eine Untersuchung der Prinzipien der Erkenntnis und der Methoden wissenschaftlicher Forschung; System der Philosophie

Grundzüge Der Psychologie, Volume 1; Philosophie Der Werte

Geschichte und Naturwissenschaft; Präludien

Die Grenzen der Naturwissenschaftlichen Begriffsbildung; Kulturwissenschaft und Naturwissenschaft

Macarius (Bulgakov), Metropolitan of Moscow and Kolomna. History of the Russian Church, Volume VII, pages 226–227.

E. Uspensky, Christian Speculation and Human Reason. The Rational Justification of the Essence of Christian Doctrine in Response to Rationalist Views on It

Ibid.

Ibid.

No citation in source text.

The Voice of an Old Professor, p. 16