The Origin of Evil

Paul Evdokimov

Translated From:

Paul Evdokimov, Dostoïevsky et le problème du mal. Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, 1978, pp 145-173.

The evil spirit of nothingness, of negation, of self-destruction. — The paradoxical nature of freedom. — The ideal possibility of evil and its experience. — The positive freedom of affirmation and the neutral freedom of choice. — The image of God, source of theoretical knowledge of evil. — The experience of freedom in Christ and its failure in man. — Double significance of the symbol of the Tree of Knowledge. — The angelic and demonic elements of human nature. — Evil prior to man. — Monist, dualist, and theandric solutions. — Notions of the Absolute and of Nothingness. — Ideal existence and empirical existence of evil. — Hypostatized evil. — First origin of evil.

“I greatly love realism… what most people call fantastic and too strange to be real, actually expresses the essence of reality”.1 “If you are capable of it and have eyes to see, you will even find in the smallest fact of real life a depth that even Shakespeare himself does not possess. It’s a matter of vision, an eye for it. Not only for writing, but also for understanding a fact, one must be an artist”.2

The realism of Dostoevsky reveals the unity of the idea and the fact, speculation and experience, and in art, the unity of form and content.

According to him, one must learn to penetrate events in all their depth, for they have value through the meaning, the idea they contain. The idea always becomes incarnate, it is the active force in relation to reality; man himself is a “word made flesh”,3 a word composed and pronounced by God and which must become intelligible to itself in its own existence.

The role of the philosopher and the poet is to reveal it. This conception of the world, in Dostoevsky, is essentially linked to his faith. The absolute value is God who reveals Himself to the world as Goodness, Beauty, and Truth. The world is created in His image and called to realize the free and creative symphony of the multiple personal elements consubstantial with God. Good always affirms the personal principle, freedom, life conceived as the unity of eternal love. Evil introduces into the world the force of negation of the absolute and its principles. It is a sickness of being, it is the principle of necessity and constraint, of isolation, of suffering and death. Evil is “the spirit of nothingness, of negation, of self-destruction”.4 “God is life”.5 Thus understood, life is the aspiration to Logos, in its fulfillment, and Satan is death and “the thirst for destruction”.6

We have already seen that Dream of a Ridiculous Man serves as a prologue to the problem of evil and can be considered a free transcription of the biblical story of the Fall. Now, if it is through man that evil enters into paradisial innocence, the tragedy of his destiny becomes more tangible; yet, the order remains the same: in relation to the conditions of paradisial being, evil appears as a secondary and fortuitous phenomenon, foreign to man’s original nature, into which it penetrates only from the experience of the knowledge of evil and after that of freedom.

Freedom escapes all determination; however, one can form an approximate notion of it by conceiving it, with Duns Scotus, as an alternative and the material possibility of an arbitrary choice: causa indeterminata ad utrumque oppositorum.

Freedom necessarily oriented toward the good, determined by it and deprived of the moment of choice, becomes a necessity in the good. True freedom presupposes that the experience of good and the experience of evil are equally possible.

Originally oriented toward the good, it has — sooner or later — a need to confront the element that opposes the good: evil.

The freedom of the created being is paradoxical, for it contains a principle of inner constraint; its dignity obliges it to realize itself as freedom, incites it to will itself in an absolute manner; it is not only given, but also proposed (not only grace, but also ascetic effort); it is a sine qua non condition of created existence.7 This character of freedom implies the possibility of evil, though not the necessity of experiencing it. The encounter with evil is determined neither by the good nor by evil; it is only a condition of the human spirit’s self-determination by a freely chosen principle.

Renouvier’s words: “Free... happy; this is a kind of antinomy before the experience of evil. The free man... had only one way to demonstrate his freedom: it was to do evil,”8 express only part of the truth. It is more accurate to say that it is choice, and not evil, that is necessary.9

Christian teleology affirms that the world will not perish senselessly and that its vocation will be fulfilled in a meeting between freedom and the divine plan for the world. Freedom is not a what but a how. Life, as a how, is freedom — and by that very fact, it is always new, always in becoming, being the continuous passage from potentiality to act. But as a what, it is the free realization, by the world, of the idea that God has conceived of it.

The experience of full autonomy of the human spirit, as it appears in the heroes of Dostoevsky, precedes the self-determination of man. Differential, positive freedom — freedom as affirmation — presupposes the indifferent, neutral freedom of choice; Saint Augustine had already noted this: he speaks of libertas major and libertas minor.

Berdyaev,10 moreover, highlights their reciprocity with particular clarity: ignorance of the first kind of freedom (arbitrary and involving choice), and failure to recognize its role within the second kind of freedom (a role similar to that of a lower category within a higher one), results in freedom in the good ceasing to be freedom at all. For Truth to “set free,” it must be freely recognized and accepted.

Certainly, freedom in the good is qualitatively different from and superior to arbitrary freedom, but it is itself unthinkable without its dialectical moment: primary freedom.11 In the system of the Grand Inquisitor, Dostoevsky offers a striking depiction of the annihilation of primary freedom. In that realm, man is forced to choose the Inquisitor’s good and to remain within it. There is neither before nor after — no alternative — and he finds himself in the realm of necessity.

Primary freedom precedes determination and, in this sense, it is groundless — ungrund — it is freedom from, but not yet freedom in or freedom through. It easily degenerates into revolt, into spiritual anarchy, into the arbitrary evaluation of values. Kirilov divinizes it, elevating arbitrariness to the level of a divine attribute; in primary freedom he finds the object of secondary freedom, such that freedom in the good appears as freedom in itself, where good and self are identified and give access to Kirilov’s man-god.

Man is destined to pass through the experience of arbitrariness, but he is not given to dwell in it or prolong the moment of choice. He may feel free even from God, but not from choice. To free him from that would require changing the ontology of man.12 The refusal to choose necessarily becomes an unconscious evil, for it implies the externalization of the principle of good.

Man can only say: “I freely become what I am — a child of freedom.” It is only in God, as the Absolute, that freedom coincides with arbitrariness. However, one must distinguish the Absolute in itself from its revelations to the world, in which the Absolute becomes the God13 of the universe, granting His absolute being and will to the conditioned principles of created being.

God reveals Himself to Dostoevsky above all as loving Freedom, and this determines the reciprocal relationship between God and the created world. God awaits a free response to His call of love.14 It is this free character of the world’s response — this free choice that allows one to recognize God as Lord and Father, to freely accept religious dependence upon Him — that necessarily requires primary freedom, with its alternative: either the free love of the good, or the possibility of its negation. And love does not depend on theoretical knowledge, but on faith, which is essentially free.15

Thus, starting from primary freedom and progressing toward secondary freedom, understood as its affirmation in the good, the dialectic of the good includes the presence of the element of evil and raises the question: Is not evil the child of the good, necessary to the freedom of the created world?

Attempts to construct a theodicy, starting from this world where evil already participates in life, come up against the problem of primary freedom. When Ivan says, “They ate the forbidden fruit, discerned good and evil, and became ‘like gods’...”,16 he speaks of an event that took place at the boundary between two states of the world, using a concrete mythological symbol from the biblical conception. From a philosophical point of view, it can be considered not as a dogmatic element but as one possible solution — one of the metaphysical ideas capable of explaining the universality of evil and its link to freedom.

If the first experience of freedom provokes the separation of two worlds, thereby defining the human destiny, then the solution to the problem of freedom and evil is found only partially in this life. The construction of the Grand Inquisitor flows logically from his refusal to go beyond the conditions of a being already tainted by evil. But here, theodicy becomes Satanodicy. The denial of the primordial fall of freedom necessarily becomes an accusatory act against God. Yet even in the Inquisitor’s system, the problem of evil remains bound to freedom; in his view, “evil” is conquered through the destruction of freedom. The great Spirit dreams of having his own “day of creation,” of a new form of being, a new anthropological type — something intermediate between the wheat and the tares — deprived of the original diversity of types through the abolition of freedom and choice.

The Inquisitor reproaches Christ for the unbearable burden of His testament of freedom: men “are naturally rebellious”;17 they possess primary freedom, but secondary freedom in Christ is not accessible to them. Only one way out remains: to suppress primary freedom. But, “You wanted to be loved freely, to be followed voluntarily by men enchanted by You. In place of the harsh old law, man was henceforth to discern good and evil with a free heart, having only Your image to guide him.”18 This is the fundamental expression of human freedom in relation to good and evil. Undifferentiated primary freedom, that of a “rebel,” if it is truly capable of grasping the value and beauty of Christ’s image, becomes — thanks to the freedom of its choice — the love of man for his God, his free affirmation in Him. But does not the image of Christ itself appear as a kind of constraint?

Man possesses a “free heart,” but his imagination is filled with images of evil that seem more powerful, because more accessible to immediate experience. The image of Christ, according to the Legend, is only a call of divine love addressed to the heart of man, now fully free in his decisions. The effects of this image can be likened to those of the image of God before the Fall.

Therein lies a response to the question: how can we conceive of victory over evil solely through the experience of freedom, without the experience of evil? In other words, is the kingdom of freedom possible apart from direct experience of the knowledge of evil?

In Dostoevsky’s work, the order of the fallen world is reflected; evil would be rejected and annihilated, its true essence laid bare and denounced19 through experiential knowledge.

Before the Fall, the experience of freedom, by virtue of the nonexistence of evil, obviously presupposes an order prior to evil; evil — or more precisely, its possibility — could have been rejected through the sole revelation and active knowledge of the essence of the good, through a genuine rooting in the good.20 For the act of accepting or refusing, obeying or disobeying, to have moral value, it must be free and conscious. From the point of view of freedom, the essence of man’s Fall lies not so much in formal disobedience—which would eliminate the very problem of freedom—as in the failure to establish oneself in a sufficiently creative way within the good, and in the insufficient development of the conscious personality meant to grow from the image of God imprinted in man. Without that creative effort from which the intuition of evil was to emerge — and without that intuition itself — the encounter of unconscious innocence with evil would be meaningless.

The knowledge of evil as purely theoretical — as an idea, as a pure possibility — comes from the image of God; for even though there is no place in God for evil, there nevertheless exists in Him an absolute knowledge of its possibility, since God is absolute plenitude.

The image of God gives man a formidable weapon against evil; it enables him to discern “with a free heart between good and evil”.21 In the person of Christ, human consciousness — without participating in the human experience of evil — nevertheless had an effective intuition of it, since it allowed for the three immortal responses that repelled Satan during the temptation in the desert. Christ’s silence before the Inquisitor signifies the definitive nature of those responses; the actual experience of evil undergone by all humanity adds nothing to the encounter between the Son of Man and the Prince of Darkness.

The temptation in the desert appears as a projection onto earth of the paradisial experience — a new trial of man’s freedom — so that human nature is once again metaphysically included in the innocence that has become transcendent to it. This accords, as we have already seen, with Dostoevsky’s conception of human destiny. But the human nature of Christ after the temptation is different from the nature of innocent man: it possesses conscious innocence, perfect integrity. The experience of freedom becomes a free affirmation of the self within absolute freedom. Evil is cast outside of Christ; His human nature has no internal affinity with evil, and every demonic element is foreign to Him. This is the meaning of the words spoken after the Last Supper: “The prince of this world cometh, and hath nothing in me.”22

But primary freedom is not eliminated from secondary freedom: “The devil, having exhausted every kind of temptation, departed from him until another occasion”23 — and this, until the moment of “it is finished.” In the desert of the spirit, in the desert of the conscience freed from all constraint, at the moment of great solitude, human nature encounters the spirit of evil; and it is in this encounter that the type of the perfect man, the “ideal of man”,24 is completed.

The problem of freedom, if posed here below, is inevitably linked to the experience of evil, simply because evil exists in the world. In the God-man, this link disappears, and consequently, a full study of freedom presupposes that we are in a position to overcome the empirical evidence of the existence of evil. Dostoevsky’s intuition moves in this direction. If Ivan is forced to say: “I humbly admit my inability to resolve such questions; I have essentially a Euclidean mind; this mind is of the earth — what good is it to try to resolve what does not belong to this world? These questions are beyond the reach of a mind that knows only three dimensions”,25 the possibility of another form of knowledge appears in the experience of the “living link that binds us to the heavenly and higher world,” revealing that “the roots of our feelings and our ideas are not here but elsewhere”.26 The conditions of this heavenly existence, having become transcendent for man, lie beyond the grasp of his reason and can now be expressed only through “myths”27 or through revelation. That is why Dostoevsky makes use of dreams and ecstasies to approach the great problems. The image of God in man makes possible a reduction of the fallen world to the temporal manifestation of paradisial being.28

The biblical myth does not oppose a tree of death to the tree of life. For the man of paradise, it is the tree of life that is essential — it is his vital principle. The tree of the knowledge of good and evil contains within itself an entirely different reality. It presents itself as something intermediate in human destiny; it is the symbol not of evil, but of its possibility — the material-natural sign of the idea of evil, an idea which man possesses through the image of God. Evil, being posterior to the experience of freedom, is external to the innocent being, and the tree of suffering and death finds no ground in paradise. The tree of knowledge is the tree of man’s conscious freedom, and it has a double significance: it is the sign of a knowledge of good and evil based only on the image of God, and it is also the sign of another knowledge that comes from the experience of evil.

Man does not feed on the fruits of this tree except after the experience of freedom — or rather, for him, to eat of it is precisely to show that his choice has been made. That is why Ivan says: “They continue to eat of it,” but according to the tree’s double meaning, the fruit itself could have been otherwise. Likewise, in the fallen world, the tree does not necessarily become the tree of death; it continues to indicate the double character of human freedom. It can become the tree of the denunciation of evil and the revelation of good.

The innocents of paradise29 formed a loving “we” in God; evil, as something foreign and unknown, was a distant “he,” external and without image. An external relationship with evil — a mere “conversation” — was not yet an act of inner communion; that is why something more was needed to bring about the Fall. Once relations with evil became an agreement with it, they momentarily created a union between man and evil: the foreign “he” became an intimate “thou”; man crossed the inner boundaries of paradise and performed an act outside of God, through which he could say to evil “we” — and then it is God who becomes the foreign “he.” The “we” of man with God is broken; love for God has degenerated into a concupiscence for the divine, which expresses itself in the phrase: “we shall be as gods.”

In the act of eating there is always, on the one hand, the eucharistic symbol of communion, and on the other, its material realization. If the tree signifies the ideal possibility of evil, then man, by eating the fruit, introduces that possibility into himself and makes it real: he allows into his being an inner conformity to evil — a demonic element hostile to God; and in doing so, he becomes a stranger to paradise and is cast out of it.

The external relationship with evil, the experience of freedom, degenerates into an internal relationship — into the experience of evil: evil, once transcendent, becomes immanent; to the angelic element of the image of God is added in man a demonic element. From now on, angels and demons will haunt the human spirit; he will be capable of experiencing both paradise and hell: “man can fall and rise again.” Evil becomes the actual atmosphere of human life, and fallen man cannot avoid experiencing it. But it is granted to him, by freely turning toward another spiritual world, to reject evil — and this is the essential subject of Dostoevsky’s works. By virtue of the metaphysical unity of the human race — at its point of origin (paradise) and its point of fulfillment (the Kingdom of God)30 — the human spirit, in entering the fallen world, becomes solidarized with the original act of the fall, accepts the laws of the universality of evil, and the unity of humankind in evil.

It is from this unity that Dostoevsky derives his fundamental idea of universal culpability and mutual, universal forgiveness. Man suddenly finds himself involved in the struggle between two worlds, and no one is exempt from this destiny, for this struggle reverberates in the very depths of the human spirit, where the duel between the devil and God is waged.31

But if man is guilty of having allowed evil to enter into the interior of human being, he is not the creator of primordial evil, just as God is not responsible for the presence of evil in man. Here, theodicy and anthropodicy are in agreement. This does not yet resolve our problem, but only presses it more closely. If evil is originally outside of man, it is nonetheless real. Where does it come from?

If Dostoevsky’s work contains no systematic constructions and presents certain gaps, nevertheless some of his ideas — such as the reciprocity of the angelic, human, and demonic planes; his definition of evil as “the spirit of nothingness, of negation, or of self-destruction”; or the general theme of freedom — seem to authorize us to deepen his perspectives concerning evil in order to grasp its origin.

God does not create evil; evil is not a moment within divine being. Nor is it the imperfection of created being, as monism claims, or an eternally independent and opposing element, as dualism affirms. Monism, in beginning from a single absolute principle, cannot account for the tragic dimension begotten by evil; it is incapable of understanding the Christian mystery of expiation, the inner tragedy of the Trinitarian God.

Dualism, on the other hand, divinizes evil by giving it being: according to this view, two eternal forces are in struggle, and in this struggle man appears as a passive and suffering instrument, deprived of freedom. Thus, if monism eliminates the tragedy of evil, dualism eliminates the tragedy of freedom. In his Christian vision of the world, Dostoevsky can accept neither dualism nor monism, and for him the problem of freedom and the problem of evil constitute one and the same question: that of the tragedy inherent to created being. This does not imply a god of evil, but a possible revolt of created being, by virtue of its freedom.

Christian thought, in affirming the principle of the created order, goes beyond monism without falling into dualism. In the divine-human union modeled on Christ, the two principles — absolute and created — are neither confused nor separated, but are nevertheless oriented toward a unity of love, infinite in its creative possibilities.

They give rise to a new creative element: the created and absolute “we”, impenetrable to reason, analogous to Trinitarian consubstantiality.32

“Being exists; nothingness does not exist.”33 Absolute being is unlimited being, and everything that is not absolute (assuming it exists) limits it and negates the very principle of absoluteness — it cannot be, does not exist, is pure nothingness. One may say that the Absolute is, and that there is absolutely nothing that limits or denies it; yet, if the Absolute exists, then absolute nothingness also exists — but only as an ideal affirmation of the absence of everything that is not the Absolute. However, it must be noted that in saying “nothingness is,” we are not affirming a specific form of being, nor even to the slightest degree.34

The notion of nothingness is a metaphysical one; moreover, it has a transcendent object. We can neither represent nor know what precedes the appearance of the world, nor what absolute disappearance would be (assuming such a thing were possible on another plane of existence), nor what lies outside of being and approaches nothingness. We take nothingness in the sense of the absolute absence of God. Reality is not spread out over nothingness; rather, nothingness is present within being as a principle of distortion, of alteration, of negation. Negation is a movement that opposes another movement — a tendency that defines itself in opposition to another tendency — and thus becomes refusal, resistance. Particular negation, bearing within itself the principle of nothingness, is defined by its opposite — by being and life in God. It is a refusal, a resistance to the Absolute and to His presence in being. Logically conceived as a second-order affirmation,35 negation thereby reveals its secondary character and possesses the formal conditions for the production of parodies, one of the essential activities of evil; and on the other hand, its powerlessness to create36 lends itself to the parasitic and counterfeit spirit — another aspect of evil.

One cannot apply the categories of empirical being to nothingness. Existing within created being, nothingness is not non-being, but something other than being. Mystical intuition defines it as the absence of God.37 But for a being subject to the laws of empirical existence, one can only approach nothingness; one cannot become nothingness. It is existential anguish — in the sense of Kierkegaard and Heidegger — that can reveal it.38

Florensky described an experience that reveals the limits of the possible and of the inexpressible:

The problem of the second death is a great problem. One day, in a dream, I experienced it in an entirely concrete way. There were no images, only inner sensations. I was surrounded by deep darkness, almost materially thick. I was being drawn by strange forces toward a boundary; I knew that it was the boundary of God’s creation, and that beyond it lay only absolute “Nothing.” I wanted to cry out, but could not. I knew that in a moment I would be cast into the outer darkness. Indeed, it began to invade my being. I had almost entirely lost consciousness, and I knew that this loss was an absolute metaphysical annihilation. At the brink of despair, I cried out: “Out of the depths I have cried.” Into those words I poured all my soul. Something seized me with force at the very moment I was sinking and hurled me away from the abyss. And suddenly, I found myself in my room, in its familiar setting; from mystical nothingness I had returned to the ordinary course of life. And I felt myself to be before the face of God.39

When we say that “between nothingness and the smallest possible fraction there is a whole metaphysical abyss,”40 we understand this as the abyss into which descends the creative act of God. “Nothingness is not the smallest conceivable form of existence; the void is not the limit of the infinitesimal” — for even at that limit, there is already the creative force of God. Nothingness, on the contrary, is an absolute absence of Being, of God. Between these two notions there lies an unbridgeable abyss; it cannot even be compared to the difference between the highest and lowest forms of existence.

Nothingness, like being, is not a moment in evolution; between them lies the transcendent act of Creation.

“Presences cannot become absences”.41 This is true in the domain of concrete being, where both presence and absence conform to the conditions of time and space, and where suppression is never anything but substitution. Absolute nothingness belongs to a different order, which implies the absence not of created being, but of absolute being — or of its creative act.

If, in created being, the absence of something always means the presence of something else, then on a higher plane, the presence of the Absolute implies the absence of its negation — the absolute nothingness of that negation.

Now, if on the absolute plane this negation is conceivable only as an ideal symbol, an imaginary sign, it is only in the created world that it can become something real: a particular force of negation aimed at denying the Absolute, at organizing life outside of God, existing within creation in the privative mode of an absolute parasite devoid of its own essence.

The inconceivable and inexpressible takes on flesh and form. Dostoevsky, in The Idiot, speaking of the principle of universal evil that seeks to replace God in the world, asks: “Can the imagination clothe in a determined form that which in reality has none? At times it seemed to me as though I saw this infinite force, this deaf, dark, and mute being materialize in a strange and indescribable way.”42

The idea of created being contains no internal contradictions; it can be realized without limiting the Absolute, remaining within Him as the object of His love, such that the idea of the created world before the creative act is a potential form of being, capable of being realized or not.

The idea of nothingness in the absolute realm is not potential nothingness, but an expression of its absolutely unrealizable character. Thus, the idea of evil exists on an entirely different plane from the idea of the created world. The latter implies the becoming of the world as being; the idea of evil, by contrast, appears as the sole form of its existence.

Furthermore, created being may be present or absent; the Absolute is not conditioned by it. On the contrary, the nothingness of the principle of negation would, in a certain sense, condition the very idea of the Absolute; and in that way, the idea of evil would be not only an idea but also a necessary ideal moment, deriving from the very absoluteness of God. It can only be thought; yet its conception is inherent to the being of the Absolute.

However, there exists a unique case in which evil is realized, being tolerated by the Absolute and limited by concrete conditions. The emergence of the force of negation would presuppose the presence of a medium heterogeneous to the Absolute, lacking necessity, and which would be a relative and free being, capable of serving as the point of application, the ontological support for this force of evil. This medium is precisely the created world, made by the Absolute and endowed with the freedom of self-determination. Not being original, this being defines itself by linking its destiny either to the absolute principles of being or of nothingness — that is, to the Absolute or to the ideal potentiality of evil. The force of negation can only arise in this world from an act of the creative will, which can bring it forth and always retains the power to cast it “outside itself.”

What is this “outside itself”43 in relation to the created world? It is not the Absolute, for the world is bound to the Absolute by its very being; that which is outside both the Absolute and the created world can only be absolute nothingness. Evil comes from its own nothingness and returns to it; as a principle of negation and of nothingness, the Absolute in itself being inaccessible to it, its action is directed against created being and its principles of existence; it ultimately aspires to total negation. Having denied all, it comes at last to deny itself. This is what Dostoevsky expresses when he says that evil is “the spirit of self-destruction and of nothingness.”44

By the original existence of the Absolute, this principle of negation is eternally reduced to ontological silence, by virtue of which it is Nothing. It is only an imaginary, unreal sign, neutralized by the fact of being necessarily folded back upon itself; it “is” in the form of nothingness, exists as non-existent,45 for to be, for it, means to negate itself. If one can say that evil exists, it exists only in order to be annihilated. Absolute being affirms itself; absolute nothingness negates itself. It appears as an ideal moment which, in order to emerge from the state of pure idea, would require a support and a summons from the created world; since this condition is not fulfilled — due to its self-enclosure and self-negation — it is eternally neutralized. Seen from eternity, the temporal process appears at once in its totality,46 and marks the transition from the ideal moment of evil’s self-negation to the real moment of its definitive disappearance from the created world, which affirms itself in the good.

Primordially, the ideal moment of evil projects itself into the world in becoming as a shadow without substance, as a pure possibility that hovers before the imagination of virgin freedom and becomes a real force through an act of the created being. This act is the passage from the ideal plane to empirical materiality, from idea to existence — analogous to the ontological argument (“the idea of God is that of the perfect being; but perfection implies real existence; therefore, the idea of God implies the real existence of its object”). This passage from idea to existence is generally regarded as flawed. The ontological argument does not achieve its goal — it does not prove the existence of God — but it does reach another goal: it proves the non-demonstrability of God by reason: Deus est Deus absconditus (God is the hidden God). And at the same time, it enables one to grasp the indemonstrable evidence of the Absolute — the existence in man of the intuition of the Absolute. Man, finding himself before the relativity of “phenomena,” has the intuition that somewhere there is a “non-relative” — there is the Absolute.47

Likewise, the passage from the ideal moment of self-negation to the real force of negation cannot be proven, but is made evident by the fact of freedom. We cannot conceive of negation within the Absolute; on the other hand, God is not the creator of evil. Yet, turning to the empirical world, we see that it is permeated by evil. Where does the first breath of negation come from — its very idea? The world is created innocent, without evil, but free and made in the image of God. God, through His omniscience of all that is possible, knows the idea of evil and its possibilities; and this knowledge is found in the pure state of the image of God — it contains the idea of the Absolute and that of nothingness. Starting from this, one can know God and form the idea of evil, can imagine it. By virtue of its freedom, the created being can direct its will toward the idea of evil, commune with the ideal moment of the negation of the good, draw it out of nothingness, and introduce it into itself.

The passage from idea to existence is precisely the very essence of every creative act: what has never existed becomes existent, and takes on the specific form of being inherent to its essence.

To the Fall — considered as the concupiscence of the divine — corresponds the authentically divine act of the creation of evil, which draws it out of nothingness. Satan, in the temptation of Adam, saying “you shall be as gods,” did not lie: the creature, for an instant, became god — it “created” evil, introduced into being the principle of negation that was external and foreign to it.

This force is not willed by God, but by the creature. In safeguarding the latter’s freedom, God not only limits Himself, but also tolerates the force of evil in the world. The desire for negation — even its very possibility — reveals the presence, within original freedom, of unenlightened elements plunging into the abyss of nothingness; the world, if it can hear the voice of God, can also hear the call of the abyss and feel the power of its own freedom by creating evil.

Once introduced, the principle of negation becomes dependent on the created world and can no longer abandon it to return to nothingness. But in its aspiration toward nothingness, it decomposes being down to its last limits, bringing with it conflict, opposition, separation, and isolation.

Yet in this process, being can escape decomposition by denouncing the essence of evil and casting it “outside itself.” Thus, the existence of evil is conditioned by the freedom of the world and, on the other hand, is limited in its activity by the divine fiat. One can weaken the bonds, one can isolate one’s life from life in God, but one cannot violate the divine act. And in this sense one may say: “negation expresses an otherness, but not a nothingness”.48 Evil is like the breath of nothingness inherent in the fallen world, bound to its destiny.

Thus, final destiny, the infernal state, and the duration of evil are, in Dostoevsky, moments immanent to the world.

The force of evil, oriented in its bearer toward the negation within him of the Absolute, seeks to spread beyond him, across the whole plane of being, in a manner analogous to the principle of the Absolute by which all things cohere and live.

The passage of evil from the ideal world into the material world presupposes that it already had an ontological place; this concrete force of negation presupposes a personification, a being who is both its creator and bearer — a spirit endowed with reason and will, in whom it becomes a hypostatized principle of evil: personal, rational, free, and possessing the power of destruction. This allows us to note what Dostoevsky often emphasizes: the nature of the evil being, its parasitic and usurping spirit, which uses the being and principles created by God for its egocentric purposes.

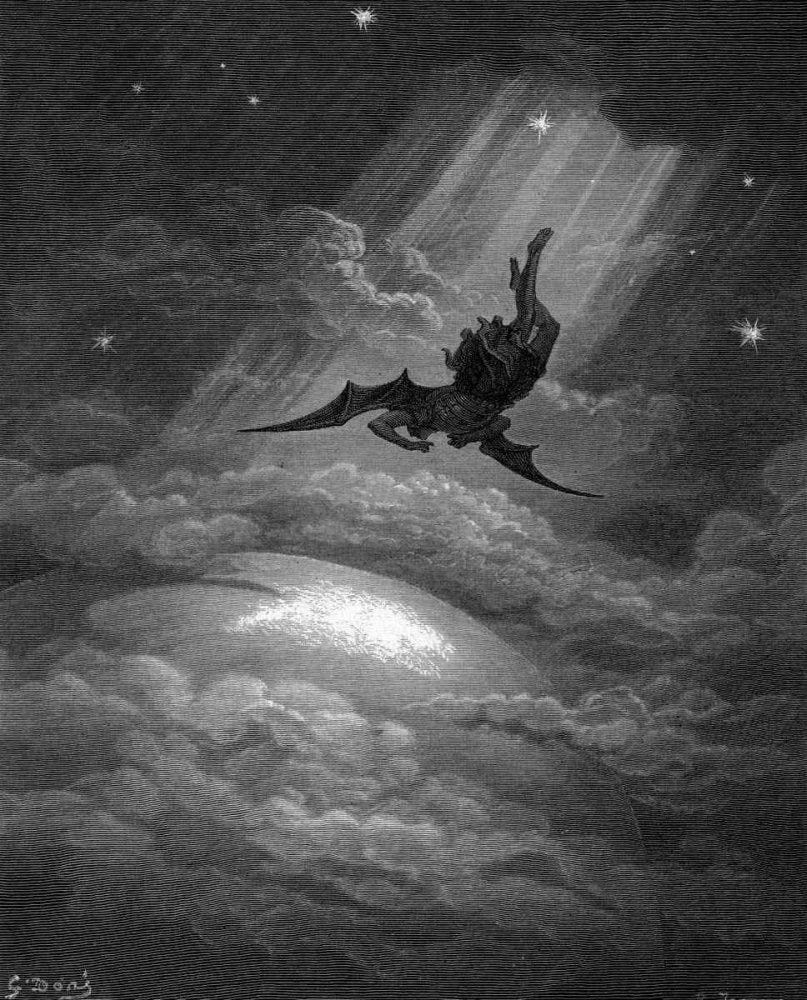

The first creator of evil, the one who “falls and can no longer rise again,” corresponds to the Lucifer of the biblical account.

The hierarchical conception of being sees in each level of being a primitive form of freedom proper to that level. Evil, called forth and introduced into the angelic realm, is limited by its particular form of freedom, and the personification of evil in Lucifer cannot be conceived in the same way as the incarnation of God in man. Lucifer was not an angelic Adam, a universal angel; the creation of evil was his personal act, which does not extend to the entire angelic realm. Conversely, evil can only be personified in the angelic realm; otherwise, it would prevent the Incarnation from being realized in its fullness in the human nature of Christ — for the Incarnation is a potential communion of the entire human plane (including the cosmos) with the divine nature of Christ.

Evil provokes a rupture in the angelic realm: one part, remaining within the limits of the experience of freedom, affirms itself forever in the good; another, through the perversion of its will, is cast outside and constitutes the infernal plane — unlike the human plane, which remains whole in the universal destiny of humanity.

The incarnation in the angelic realm is unnecessary, because of its definitive affirmation in the good; in the infernal plane, it is impossible, because it would amount to violating a freedom that is already conscious. It is possible only in the human plane, due to the special nature of human freedom in becoming. The human plane lies at the center of creation: the angelic world protects man; the infernal world seeks to subjugate him.

This is the anthropocentrism of the world so dear to Dostoevsky: man falls and rises again; he is ontologically immersed in the alternative between the angelic and demonic planes — but something belongs to him alone: to be angel and demon while remaining man; to be able to fall, and to be able to rise. Human freedom reaches into the angelic and infernal planes, which come together in the soul of man as “other worlds” and are experienced by him as the angelic and demonic elements of his ontology.

The failure of the experience of freedom in both man and angel comes from the same temptation: “you shall be as gods.” Evil is a principle of deviation, of perversion of the will. The original Fall shows that between God and His child there is a mysterious kinship: the very form of the temptation proves it — it was born precisely from the resemblance of the creature to the Creator. In the spiritual world, Lucifer was to be a kind of alter ego of God, and only for this reason could the primitive perversion of the will — the first movement toward equality, the transition from resemblance to identity — have occurred.49 Because of his dignity as a faithful reflection of God Himself, he passes through the dizzying point of his free self-definition, and here the image of God in him becomes a double-edged sword: through this image, like God, the innocent being possessed a theoretical knowledge of the possibility of evil; and through his freedom in becoming, he had the terrible power to use this knowledge as he wished. Here we sense the solution to the painful enigma of the first origin of evil, and from here unfolds the grand perspective of Theodicy.

The natural and good orientation of the will in Lucifer stops at the idea of evil as a purely imaginary possibility of having different relations with the Absolute Thou of his God. He makes this idea his own, communes with it; the impulse of love directed toward the being of God changes its object and degenerates into concupiscence directed toward the idea of the divine, toward the possession of God’s attributes.

The idea of the divine replaces the being of God. The idea of atheism thus finds its point of departure.

In wanting to separate God’s attributes from God’s very being, Lucifer sees the image of God in himself altered — it is split in two. Lucifer’s destiny is henceforth tied to the attributes, to the idea of the divine. Finding himself alienated from the very being of God, the essential content of his life becomes the concupiscence for power and domination — the empire of evil.

The universal being whom God had predestined for free love is usurped and used by evil, which seeks to make itself equal to God, for the construction of a kingdom according to “its own plan,” in which the idea of the creature and the awareness of being a child of God will be destroyed.

The formula “you shall be as gods” is also projected into the human plane: man becomes god by creating within himself the demonic element; and by virtue of the primordial unity of the human race, he causes all humanity to commune in evil.

In the angelic plane, as in the human plane, there is no original, direct, or necessary link to evil. In the case of the angels, freedom was conditioned solely by the ideal moment of evil, by its potentiality. Likewise, in man, freedom was linked only to the possibility of evil — which could have remained eternally external to the human plane; the decisive moment was that of the free act of the human will.

Man finds himself outside of God; the shame in the biblical account symbolizes communion with an external and foreign plane to which man will now closely bind his destiny — his freedom now determined by the real existence of evil.

Fiodor Dostoïevsky, Carnets de Dostoïevsky, cited by Dmitri Mérijkovsky in Tolstoï et Dostoïevsky (Paris: Perrin, 1923), 329. English translation Dmitri Merezhkovsky, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky: A Study of the Christian Idea of Man. Translated by Natalie Duddington (London: Sheed and Ward, 1930).

Fiodor Dostoïevsky, Carnets des Frères Karamasoff, 15. English translation Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Notebooks for The Brothers Karamazov, trans. Edward Wasiolek (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971).

Ibid., 91.

Fiodor Dostoïevsky, Légende du Grand Inquisiteur; translated as Fyodor Dostoevsky, “The Legend of the Grand Inquisitor,” in The Brothers Karamazov, trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1990).

Life is an experience of God, not through something that symbolizes Him, but through the very reality of God. This experience is never a proof, but a direct and immediate communion, for one can never objectify Him. God is not an object; He is the absolute Self. See Gabriel Marcel, Journal métaphysique [Metaphysical Journal, trans. Virginia Moore (Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1952)]. Existential experience teaches that certainty about God does not reside in proofs of His existence, but in the interiority through which the person experiences their relationship with God.

Dostoïevsky, Carnets des Frères Karamasoff, 156.

William Shakespeare, Measure for Measure, act 2, scene 1: “’Tis one thing to be tempted, another thing to fall.”

Charles Renouvier, La Nouvelle Monadologie (Paris: Alcan, 1899), 465.

Schelling, in Philosophische Untersuchungen über das Wesen der menschlichen Freiheit [Philosophical Investigations into the Essence of Human Freedom], sees evil in the will to exist for oneself and to become, for oneself, one’s own universe — a sphere closed to universal love. It is because the unity of personality is broken that the passions break in. He gives to egoism and to love a metaphysical depth so profound that human freedom appears to carry within itself the resolution of cosmic destinies. Yet the human will is not determined, but only drawn toward evil (p. 373). Personality, free and becoming, seems determined when viewed from the outside, but when seen from within and in itself, it is freedom (pp. 382–389). The difference between Schelling and the Christian conception begins where Schelling sees in evil the first stage of a theogony, and in nature a necessity for the becoming of God. In the personalism of the Christian conception, the personal being is primordial and superior to the impersonal. The creation of the world is not a necessity of divine ontology, but the infinite richness of His love; God existing, it is the world that demands its own existence in order to come to know divine love.

Nicolas Berdiaeff, Esprit et liberté (Paris: Aubier, 1933), chap. IV; English translation Freedom and the Spirit, trans. Oliver Fielding Clarke (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1935).

“Lermontov, Tyutchev, Gogol, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky — all adore the primal, anarchic, autonomous force; they desire only its freedom, and at the same time, what a nostalgia they show for holiness, perfection, beauty, and peace. Each one, at the cost of unspeakable anguish, seeks in his own way a way out.” — [Mikhail] Gershenzon, cited in Борис Вышеславцев, Русская стихия у Достоевского [Boris Vysheslavtsev, The Russian Element in Dostoevsky] (Берлин: Издательство Путь, 1923); the two freedoms are clearly represented here.

It is in this that the “transfiguration” of the Inquisitor consists.

“Deus vox relativa, Deus significat Dominus.” — Isaac Newton. Cited in Charles Secrétan, La Philosophie de la liberté : l’histoire, 304.

The essence of Christ’s “Testament of freedom” in The Legend of the Grand Inquisitor.

See The Brothers Karamazov.

Fiodor Dostoïevski, Les Frères Karamazov, trans. Henri Mongault (Paris: Éditions Bossard, 1923), vol. 1, 359.

Ibid., vol. 1, 379.

Ibid., vol. 1, 384.

“Having touched the nothingness of pleasure, he longs for the absolute of God.” Guillain de Bénouville, Baudelaire le trop chrétien (Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1936), 53.

This rooting can only be creative; indeed, according to the biblical account itself, Adam is called not only to labor but also to creative acts — for example, the naming of the animals. Renouvier emphasizes that the first attribute of God is that of creation. See [Octave] Hamelin, Le Système de Renouvier (Paris: Librairie Philosophique J. Vrin, 1927).

Dostoïevski, Les Frères Karamazov, vol. 1, 384.

St John 14:30

St Luke 4:13

It is on the mountains, on the heights of his spirit, that man is visited by God. The anthroposophists rightly emphasize the symbolic significance of the mountain. See R[udolf] Frieling: Der Heilige Berg im alten und neuen Testament.

Dostoïevski, Les Frères Karamazov, vol. 1, 355.

Ibid., vol. 2, 62.

Sin is a rupture with paradisial immanence; it is a new quality which, in establishing itself, also establishes the beginning of History. That is why it can only be spoken of through a myth.

This explains the mystical vision of the world as paradise in Zosima and Makar.

The Dream of a Ridiculous Man

Adam Kadmon of the Kabbalah, the first and second Adam in the theology of Saint Paul.

Dostoïevski, Les Frères Karamazov, vol. 1, 170.

The Trinity, an absolutely irrational concept, is rationalized and decomposed by Viale, who reduces it to duality and unity. This approach eliminates the mystery by stripping it of its content and demonstrates that the Trinitarian principle of God is inaccessible to rational thought. (L. Viale, L’Amour dans l’Univers.)

Fiodor Dostoïevski, Carnets des Possédés, 605. English trans. Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Notebooks for The Possessed, ed. Edward Wasiolek, trans. Victor Terras (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968).

Frédégisus, a student of Alcuin, in the Epistola de nihilo et tenebris, crudely argues — based on a coarse realism — that nothingness (nihil) exists, because to say that it is nothing implies that it is.

Henri Bergson, Creative Evolution.

Negation, as a second-order affirmation, cannot create sui generis ideas.

“The religious soul experiences... the remoteness of the divine presence.” J. Segond, Traité de psychologie (Paris: Librairie Armand Colin, 1930), 277.

See Martin Heidegger, Qu’est-ce que la métaphysique?, trans. Henry Corbin (Paris: Gallimard, 1951), 31. English trans. What Is Metaphysics?, trans. David Farrell Krell, in Basic Writings, ed. David Farrell Krell (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1993).

Pavel Florensky, La Colonne et le fondement de la vérité, trans. Constantin Andronikof (Lausanne: L’Âge d’Homme, 1975), 205. English trans. Pavel Florensky, The Pillar and Ground of the Truth: An Essay in Orthodox Theodicy in Twelve Letters, trans. Boris Jakim (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997).

See the critique of the idea of nothingness in Bergson, Énergie spirituelle, pp. 132–135; L’Évolution créatrice, pp. 233, 258, 296, 323. English trans. Henri Bergson, Mind-Energy: Lectures and Essays, trans. H. Wildon Carr (London: Macmillan, 1920); and Creative Evolution, trans. Arthur Mitchell (New York: Henry Holt, 1911).

Bergson, L’Évolution créatrice, p. 266.

Fyodor Dostoevsky, L’Idiot, t. II, trans. Henri Mongault (Paris: Gallimard, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, 1950), 729. English trans. Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Idiot, trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (New York: Everyman’s Library, 2002).

The “outer darkness” of which the Gospel speaks (St Matthew 8:12).

Dostoïevski, Les Frères Karamazov, vol. I, p. 379. The French translation: “l’esprit de la destruction” is not accurate.

According to Schelling, evil never is, but always strives to be.

Boethius, in his De consolatione philosophiae, says that the intelligence of God sees all “with one stroke of the mind” (uno ictu mentis), book III, p. 5.

Immediately there arises absolute reality. “If God is not, God is.” See V. Vysheslavtsev, Éthique de l'Éros transfiguré, pp. 234, 237. “We can think of the relative or the conditioned only because we conceive of the unconditioned and the absolute.” A. Spir, Pensée et réalité, p. 9. Cf. Herbert Spencer, First Principles, vol. II, chs. 1 and 2.

Vladimir Jankélévitch, Henri Bergson, 3rd ed. (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1959), 250. English trans. Vladimir Jankélévitch, Henri Bergson, trans. Nils F. Schott, ed. Nils F. Schott and Alexandre Lefebvre (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015).

Gregory the Great, Moralia in Job, lib. IV, cap. 9, in PL 75, 644; trans. Brian Kerns, O.C.S.O., Morals on the Book of Job, vol. 1: Preface and Books 1–5 (Collegeville, MN: Cistercian Publications, 2014).