Toll the Bell

Stephen Graham

Originally published in

The Quest of the Face. New York: Macmillan Company, 1918.

The thought that people are and then are not was my despair, that people have once been but are not now, are not even remembered but lost.

Toll the bell! Toll the bell for the dead! Pray for the poor dying men and women! Light the candles and weep for the dead, for the living who have entered the great darkness! For the living who are entering it in thousands whilst we think!

Think of those whose bright faces were turned away from us ages ago, of those whom you have forgotten, whom every one in the world has forgotten, whom no one of any coming age shall ere recall. They are lost in the vast outer limbo, which is so much greater than the narrow sphere of memory. That is our despair, the despair even of a Christ-seeker. We have all to enter it, not only the first twilight of memory but the outer darkness of complete oblivion wherein myriads are lost.

There are nights which the days succeed. They begin with radiant sunset that promises a morrow. Day follows night, day follows night, day follows night, but at last comes a night that no day follows. The twilight is murky and without promise, and night comes on without stars, and lamps are lit and burn low, and are replenished with oil and burn again, and again burn low and flicker, and again are replenished and again burn out, and night goes on. It goes on till all the oil in the world is burnt, and on and on for ever, intense, silent, black, and breathless.1

We are lighting lamps for Solomon and Homer and Dante and Shakespeare, but they and all the rest recede. All our dead have entered the darkness, and when we write of them or call their faces back to memory we are lighting the lamps — we light them, succeeding generations light them, but at last a generation comes that has no oil.

I mused in this way as I lay in bed in the oppressive darkness of my room. And the face of the dead man whom I had seen remained pale and sad in my memory and yet vivid as if the moon were shining upon it. The face of one who was destined to oblivion, a face also near to that of Christ.

Next morning my dear professor joined me at breakfast, and ruffling his hair with both hands, exclaimed in a distracted way:

“What a morning, what a morning!”

“Yes, it is a lovely morning,” said I.

“Oh, not that I mean, not that I mean,” replied the professor with chagrin. “It is Marathon morning, my dear fellow, the anniversary of Marathon, think of it!”

And the sun streamed through the upper panes of the windows, lightening his silvery hair and my gaunt haggard cheeks.

“Its memory shall never pass away,” said the professor. We opened the Times. Its pages were replete with the casualties of a great battle, a long list of the dead printed in small type.

“But the memory of those who died at Marathon has gone,” said I.

“No, no,” said the professor. “They are remembered. Each of these names you see here has his home where for generations they will be proud of him. It is glorious, it is moving, my dear fellow, moving — ”

“We have not, alas, the Marathon casualty list that we might look it over,” said I coldly.

“But we have, we have,” said the professor, and he flattened out the newspaper before me, and I smiled.

A strange thought suffused my mind, and I suppose it came from the professor’s faith — even those who died at Marathon are alive in Christ.

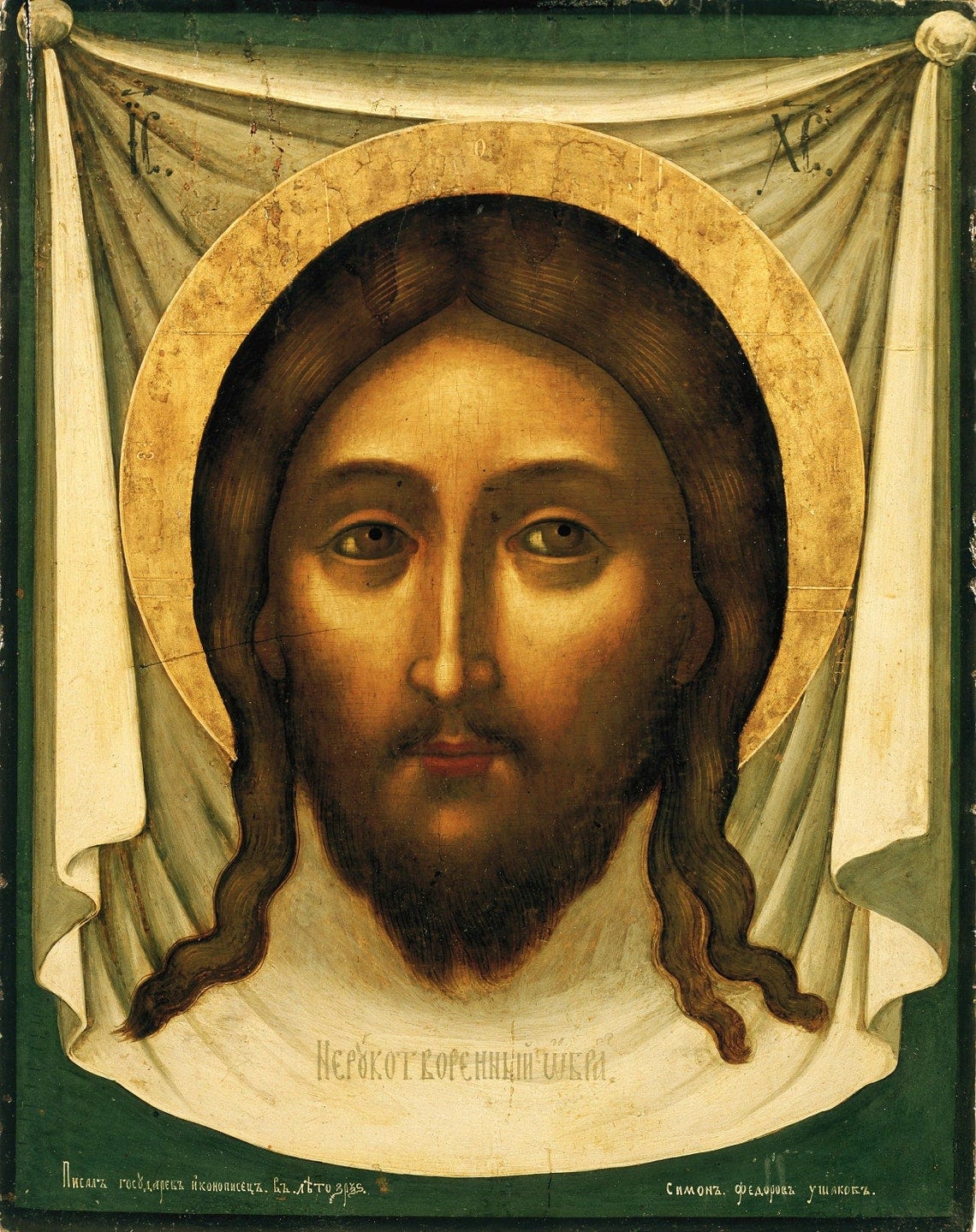

I have no doubt it is true. For as in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive. By Christ, in some mysterious way, all who died even before He was born must be saved also. He is the link between the living and the dead, and looking on the dead man’s face one is suddenly, as it were, aware of Him. The face of Christ can be descried from the gate of death. Even so. The Eastern mediaeval portrait such as I have seen on old ikons is a reflection from the face of the dead — brown, wizened, wrinkled and unearthly. That portrait is a saying Nay to this life in favour of some other life to which death is nearer.

Pity for the forgotten dead and for those who now seem to lie in dissolution, and also terror, all incline us to raise up the effigy of the dead as Christ. They incline me also.

Nevertheless I fervently believe that Christ is to be found in the faces of the living. Christ walks perdu among the flocking crowd, and I might find Him in a human face. His face lurks in the face of some one who has passed me. If the face which is a reflection of death be authentic I should be able to find that face in the human faces which go by. The quest cannot be vain: I can and will find the face that I seek. A dead man could not play in my mystery play, though he might prompt some words of the drama. The word is good, but I must also have the life. I look at men’s faces afresh but I do not see death. I see mortality, foreknowledge of death, but not death itself. Sad faces, tired faces, jaded faces, the faces of the dying, of those condemned to death — but all have in them life. ‘Tis true no one seems to be completely and absolutely alive. It would take four or five of these pitiful fractional brother humans of the street to make up one face which should be wholly alive. Perhaps more. But no number would add up to death. It is impossible to see the dead man Christ standing in the background of a man, behind his eyes. And for that reason, though seemingly death is in proximity to Christ, I decide not to accept the guidance of the face of the dead man. Christ is no corpse tied to a living man’s back.

There is in men’s features something unwonted, something unusual. The most ordinary face as well as the most striking and unusual gives a hint of something or some one other than himself. It is not a likeness to any one I know, but a likeness to some one I have not seen. Perhaps they have to develop the likeness more, or I have to develop the eyes that see more. But I have a feeling that the mystery is a large one. It draws me on, and it is because of it that I feel the face is to be found thus, and though I accept the help of so-called portraits I do not accept the portraits as a substitute. The Living One is my only authenticity.

Editor’s note: I recall the following passage from the 1966 “Dutch Catechism” (A New Catechism: Catholic Faith for Adults): “Then there is death that casts a shadow on every yearning. Men may have a happier future, and build a strong city of freedom and brotherhood, but it will still have a gate opening on the dark, through which men will go all the more sadly, the happier the city, the better mankind.” The image of a “gate opening on the dark” has remained with me.