From Berdyaev, Nicolas. The Destiny of Man. Translated by Natalie Duddington. London: G. Bles, The Centenary Press, 1937. Part II:III:3, pp 182—196

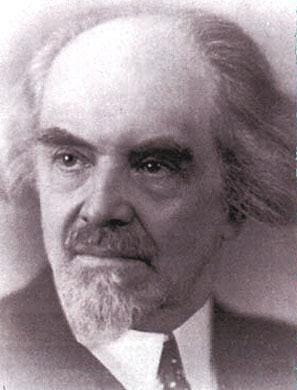

As I always observe when referring to Berdyaev, Orthodox readers who are taken aback by his perspective should remember that he was not one of those intellectuals far from the life of the Church — he was the spiritual son of a great confessor of the faith, St Alexei Mechev. On St Alexei, more here:

The ethics of creativeness presupposes that the task which confronts man is infinite and the world is not completed. But the tragedy is that the realization of every infinite task is finite. Creative imagination is of fundamental importance to the ethics of creativeness. Without imagination there can be no creative activity. Creativeness means in the first instance imagining something different, better and higher. Imagination calls up before us something better than the reality around us. Creativeness always rises above reality. Imagination plays this part not only in art and in myth making, but also in scientific discoveries, technical inventions and moral life, creating a better type of relations between human beings. There is such a thing as moral imagination which creates the image of a better life—it is absent only from legalistic ethics.1 No imagination is needed for automatically carrying out a law or norm. In moral life the power of creative imagination plays the part of talent. By the side of the self-contained moral world of laws and rules to which nothing can be added, man builds up in imagination a higher, free and beautiful world lying beyond ordinary good and evil. And this is what gives beauty to life. As a matter of fact life can never be determined solely by law — men always imagine for themselves a different and better life, freer and more beautiful, and they realize those images. The Kingdom of God is the image of a full, perfect, beautiful, free and divine life. Only law has nothing to do with imagination, or, rather, it is limited to imagining compliance with, or violation of, its behests. But the most perfect fulfilment of the law is not the same as the perfect life.

Imagination may also be a source of evil — there may be bad imagination and phantasms. Evil thoughts are an instance of bad imagination. Crimes are conceived in imagination. But imagination also brings about a better life. A man devoid of imagination is incapable of creative moral activity and of building up a better life. The very conception of a better life towards which we ought to strive is the result of creative imagination. Those who have no imagination think that there is no better life at all and there ought not to be. All that exists for them is the unalterable order of existence in which unalterable law ought to be realized. Jacob Boehme ascribed enormous importance to imagination.2 The world is created by God through imagination, through images which arise in God in eternity and are both ideal and real. Modern psychologists and alienists also ascribe great importance to imagination, both good and bad. They have discovered that imagination plays an infinitely greater part in people’s lives than has been thought hitherto. Diseases and psychoses arise through imagination and can also be cured through it. The ethics of law forbids man to imagine a better world and a better life, it fetters him to the world as given and to the socially organized herd life, laying down taboos and prohibitions everywhere. But the ethics of creativeness breaks with the herd-existence and refuses to recognize legalistic prohibitions. To the law of the present life it opposes the image of a higher one.

The ethics of creativeness is the ethics of energy. Quantitative and qualitative increase in life’s intensity and creative energy is one of the criteria of moral valuation. The good is like radium in spiritual life and its essential quality is radio-activity, inexhaustible radiation. The conceptions of energy and that of norm come into conflict in ethics. The morality of law and the morality of creative energy are perpetually at war. If the good is understood as a real force, it cannot be conceived as the purpose of life. A perfect and absolute realization of the good would make it unnecessary and lead us completely to forget moral distinctions and valuations. The nature of the good and of moral life presupposes dualism and struggle, i.e. a painful and difficult path. Complete victory over the dualism and the struggle leads to the disappearance of what, on the way, we had called good and moral. To realize the good is to cancel it. The good is not at all the final end of life and of being. It is only a way, only a struggle on the way. The good must be conceived of in terms of energy and not of purpose. The thing that matters most is the realization of creative energy and not the ideal normative end. Man realizes the good not because he has set himself the purpose of doing so but because he is good or virtuous, i.e. because he has in him the creative energy of goodness. The source is important and not the goal. A man fights for a good cause not because it is his conscious purpose to do so, but because he has combative energy and the energy of goodness. Goodness and moral life are a path in which the starting point and the goal coincide—it is the emanation of creative energy.

But from the ontological and cosmological point of view, the final end of being must be thought of as beauty and not as goodness. Plato defined beauty as the magnificence of the good. Complete, perfect and harmonious being is beauty. Teleological ethics is normative and legalistic. It regards the good as the purpose of life, i.e. as a norm or a law which must be fulfilled. Teleological ethics always implies absence of moral imagination, for it conceives the end as a norm and not as an image, not as a product of the creative energy of life. Moral life must be determined not by a purpose or a norm but by imagery3 and the exercise of creative activity. Beauty is the image of creative energy radiating over the whole world and transforming it. Teleological ethics based upon the idea of the good as an absolute purpose is hostile to freedom, but creative ethics is based upon freedom. Beauty means a transfigured creation, the good means creation fettered by the law which denounces sin. The paradox is that the law fetters the energy of the good, it does not want the good to be interpreted as a force, for in that case the world would escape from the power of the law. To transcend the morality of law means to put infinite creative energy in the place of commands, prohibitions, and taboos.

Instinct plays a twofold part in man’s moral life — it dates back to ancient, primitive times, and ancient terror, slavishness, superstition, animalism and cruelty find expression in it — but at the same time it is reminiscent of paradise, of primitive freedom and power, of man’s ancient bond with the cosmos and the primeval force of life. Hence the attitude of the ethics of creativeness towards instincts is complex — it liberates instincts repressed by the moral law and at the same time struggles with them for the sake of a higher life. Instincts are repressed by the moral law, but since they have their origin in the social life of primitive clans, they themselves tend to become a law and to fetter the creative energy of life. Thus, for instance, the instinct of vengeance is, as has already been said, a heritage of the social life of antiquity and is connected with law. The ethics of creativeness liberates not all instincts but only creative ones, i.e. man’s creative energy hampered by the prohibitions of the law. It also struggles against instincts and strives to sublimate them.

Teleological ethics, which is identical with the ethics of law, metaphysically presupposes the power of time in the bad sense of the word. Time is determined either by the idea of purpose which has to be realized in the future or by the idea of creativeness which is to be carried out in the future. In the first case, man is in the power of the purpose and of the time created by it, in the second he is the master of time for he realizes in it his creative energy. The problem of time is bound up with the ethics of creativeness. Time and freedom are the fundamental and the most painful of metaphysical problems. Heidegger, in his Sein und Zeit, formulates it in a new way, but he connects time with care and not with creativeness. There can be no doubt, however, that creativeness is connected with time. It is usually said that creativeness needs the perspective of the future and presupposes changes that take place in time. In truth, it would be more correct to say that movement, change, creativeness give rise to time. Thus we see that time has a double nature. It is the source both of hope and of pain and torture. The charm of the future is connected with the fact that the future may be changed and to some extent depends upon ourselves. But to the past we can do nothing, we can only remember it with reverence and gratitude or with remorse and indignation. The future may bring with it the realization of our desires, hopes and dreams. But it also inspires us with terror. We are tortured with anxiety about the unknown future. Thus the part of time which we call the future and regard as dependent upon our own activity may be determined in two ways. It may be determined by duty, by painful anxiety and a command to realize a set purpose, or by our creative energy, by a constructive vital impulse through which new values are coined. In the first case time oppresses us, we are in its power. The loftiest purpose projected into the future enslaves us, becomes external to us and makes us anxious. Anxiety is called forth not only by the lower material needs but also by the higher ideal ends. In the second case, when we are determined by the free creative energy, by our free vital force, we regard the future as immanent in us and are its masters. In time everything appears as already determined and necessary, and in our feeling of the future we anticipate this determinateness — events to come appear sometimes to us as an impending fate. But a free creative act is not dominated by time, for it is not determined in any way — it springs from the depths of being, which are not subject to time, and belongs to a different order of existence. It is only later that everything comes to appear as determined in time. The task of the ethics of creativeness is to make the perspective of life independent of the fatal march of time, of the future which terrifies and torments us. The creative act is an escape from time, it is performed in the realm of freedom and not of necessity. It is by its very nature opposed to anxiety which makes time so terrible. And if the whole of the human life could be one continuous creative act, there would be no more time — there would be no future as a part of time — there would be movement out of time, in non-temporal reality. There would be no determination, no necessity, no binding laws. There would be the life of the spirit. In Heidegger reality subject to time is a fallen reality, though he does not make clear what was its state before the Fall. It is the realm of the “herd man.” It is connected with care for the future and anxiety. But Christ teaches us not to care about the future. “Enough for the day is the evil thereof.” This is an escape from the power of time, from the nightmare of the future born of anxiety.

The future may or may not bring with it disappointment, suffering and misfortune. But certainly, and to everyone, it brings death. And fear of the future, natural to everyone, is in the first place fear of impending death. Death is determined for everyone in this world, it is our fate. But man’s free and creative spirit rises against this slavery to death and fate. It has another vista of life, springing from freedom and creativeness. In and through Christ the fate of death is cancelled, although empirically every man dies. Our attitude to the future which ends for us in death is false because, being divided in ourselves, we analyse it and think of it as determined. But future is unknowable and cannot be subjected to analysis. Only prophecy is possible with regard to it, and the mystery of prophecy lies precisely in the fact that it has nothing to do with determinations and is not knowledge within the categories of necessity. For a free creative act there exist no fate and no pre-determined future. At the moment when a free creative act takes place there is no thought of the future, of the inevitable death, of future suffering — it is an escape from time and from all determinateness. In creative imagination the future is not determined. The creative image is outside the process of time, it is in eternity. Time is the child of sin, of sinful slavery, of sinful anxiety. It will stop and disappear when the world is transfigured. But transfiguration of the world is taking place already in all true creativeness. We possess a force by means of which we escape from time. That creative force is full of grace and saves us from the power of the law. The greatest moral task is to build up a life free from determinateness and anxiety about the future and out of the perspective of time. The moral freedom to do so is given us, but we make poor use of it.

Freedom requires struggle and resistance. We are therefore confronted with the necessarily determined everyday world in which processes are taking place in time and the future appears as fated. Man is fettered and weighed down. He both longs for freedom and fears it. The paradox of liberation is that in order to preserve freedom and to struggle for it, one must in a sense be already free, have freedom within oneself. Those who are slaves to the very core of their being do not know the name of freedom and cannot struggle for it. Ancient taboos surround man on all sides and fetter his moral life. In order to free himself from their power man must first be conscious of himself as inwardly free and only then can he struggle for freedom outwardly. The inner conquest of slavery is the fundamental task of moral life. Every kind of slavery is meant here — the slavery to the power of the past and of the future, the slavery to the external world and to oneself, to one’s lower self. The awakening of creative energy is inner liberation and is accompanied by a sense of freedom.4 Creativeness is the way of liberation. Liberation cannot result in inner emptiness — it is not merely liberation from something but also liberation for the sake of something. And this for the sake of is creativeness. Creativeness cannot be aimless and objectless. It is an ascent and therefore presupposes heights, and that means that creativeness rises from the world to God. It moves not along a flat surface in endless time but ascends towards eternity. The products of creativeness remain in time, but the creative act itself, the creative flight, communes with eternity. Every creative act of ours in relation to other people — an act of love, of pity, of help, of peacemaking — not merely has a future but is eternal.

Victory over the categories of master and slave5 in the moral life is a great achievement. A man must not be the slave of other men, nor must he be their master, for then other people will be slaves. To achieve this is one of the tasks of the ethics of creativeness which knows nothing of mastery and slavery. A creator is neither a slave nor a master, he is one who gives and gives abundantly. All dependence of one man upon another is morally degrading. It is incomprehensible how the slavish doctrine that a free and independent mind is forsaken by the divine grace could ever have arisen. Where the Spirit of God is, there is liberty. Where there is liberty, there is the Spirit of God and grace. Grace acts upon liberty and cannot act upon anything else. A slavish mind cannot receive grace and grace cannot affect it. But slavish theories which distort Christianity build up their conception of it not upon grace and liberty but upon mastery and slavery, upon the tyranny of society, of the family and the state. They generally recognize free will but only for the sake of urging it to obedience. Free will cannot, however, be called in merely to be threatened. The freedom of will which has frequently led to man’s enslavement must itself be liberated, i.e. imbued with gracious force. Creativeness is the gracious force which makes free will really free, free from fear, from the law, from inner dividedness.

The paradox of good and evil — the fundamental paradox of ethics — is that the good presupposes the existence of evil and requires that it should be tolerated. This is what the Creator does in allowing the existence of evil. Hence absolute perfection, absolute order and rationality may prove to be an evil, a greater evil than the imperfect, unorganized, irrational life which admits of a certain freedom of evil. The absolute good incompatible with the existence of evil is possible only in the Kingdom of God, when there will be a new heaven and a new earth, and God will be all in all. But outside the Divine kingdom of grace, freedom and love, absolute good which does not allow the existence of evil is always a tyranny, the kingdom of the Grand Inquisitor and the antichrist. Ethics must recognize this once and for all. So long as there exists a distinction between good and evil, and consequently our good which is on this side of the distinction, there must inevitably be a struggle, a conflict between opposing principles, and resistance, i.e. exercise of human freedom. The absolute good and perfection outside the Kingdom of God turns man into an automaton of virtue, i.e. really abolishes moral life, since moral life is impossible without spiritual freedom.

Hence our attitude to evil must be twofold — we must be tolerant of it as the Creator is tolerant, and we must mercilessly struggle against it. There is no escaping from this paradox, for it is rooted in freedom and in the very fact of distinction between good and evil. Ethics is bound to be paradoxical because it has its source in the Fall. The good must be realized, but it has a bad origin. The only thing that is really fine about it is the recollection of the beauty of Paradise.

Is the struggle waged in the name of the good in this world an expression of the true life, “first life”? Is it not bound by earthly surroundings and is it not only a means to life? And how can first life, life in itself, be attained? We may say with certainty that love is life-in-itself, and so is creativeness, and so is the contemplation of the spiritual world. But this life-in-itself is absent from a considerable part of our legalistic morality, from physiological processes, from politics and from civilization. First life or life-in-itself is to be found only in the first-hand, free moral acts and judgments. It is absent from moral acts which are determined by social environment, heredity, public opinion, party doctrines, etc., i.e. it is absent from a great part of our moral life. True life is only to be found in moral acts in so far as they are creative. Automatic fulfilment of the moral law is not life. Life is always an expansion, a gain. It is present in first-hand aesthetic perceptions and judgments and in a creatively artistic attitude to the world, but not in aesthetic snobbishness.

Nietzsche thought that morality was dangerous because it hindered the realization of the higher type of man. This is true of legalistic morality, which does not allow the human personality to express itself as a whole. In Christianity itself legalistic elements are unfavourable to the creative manifestation of the higher type of man. The morality of chivalry, of knightly honour and loyalty, was creative and could not be subsumed under the ethics of law or the ethics of redemption. And in spite of the relative, transitory and even bad characteristics which chivalry has had as a matter of historical fact, it contained elements of permanent value and was a manifestation of the eternal principles of the human personality. Chivalry would have been impossible without Christianity.

Nietzsche opposes to the distinction between good and evil, which he regards as a sign of decadence, the distinction between the noble and the low. The noble, the fine, is a higher type of life, aristocratic, strong, beautiful, well-bred. The conception of fineness is ontological while that of goodness is moralistic. This leads not to a-moralism which is a misleading conception, but to the subordination of moral categories to the ontological. It means that the important thing is not to fulfil the moral law but to perfect one’s nature, i.e. to attain transfiguration and enlightenment. From this point of view the saint must be described as fine and not as good, for he has a lofty, beautiful nature penetrated by the divine light through and through. But all Nietzsche knew of Christianity was the moral law, and he rebelled against it. He had quite a mistaken idea about the spirit and spiritual life. He thought that a bad conscience was born of the conflict between the instincts and the behests of the society-just as Freud, Adler and Jung suppose. The instinct turns inwards and becomes spirit. Spirit is the repressed, inward-driven instinct, and therefore really an epiphenomenon. The true, rich, unrepressed life is for Nietzsche not spirit and indeed is opposed to it. Nietzsche is clearly the victim of reaction against degenerate legalistic Christianity and against the bad spirituality which in truth has always meant suppression of the spirit. Nietzsche mistook it for the true spirituality. He rejected God because he thought God was incompatible with creativeness and creative heroism to which his philosophy was a call. God was for him the symbol not of man’s ascent to the heights but of his remaining on a flat surface below. Nietzsche was fighting not against God but against a false conception of God, which certainly ought to be combated. The idea, so widely spread in theology, that the existence of God is incompatible with man’s creativeness is a source of atheism. And Nietzsche waged an agonizing struggle against God. He went further and asserted that spirit is incompatible with creativeness, while in truth spirit is the only source of creativeness. In this connection, too, Nietzsche’s attitude was inspired by a feeling of protest. Theology systematically demanded that man should bury his talents in the ground. It failed to see that the Gospel required creativeness of man and confined its attention to commands and laws — it failed to grasp the meaning of parables and of the call to freedom — it sought to know only the revealed and not the hidden. Theologians have not sufficiently understood that freedom should not be forced, repressed and burdened with commands and prohibitions. Rather it ought to be enlightened, transfigured and strengthened through the power of grace. A curious paradox is exemplified in the teaching of the Jesuits.6 Jesuitism is in a sense an apotheosis of the human will — a man may increase the power of God. Jesuitism teaches a new form of asceticism — asceticism of the will and not of the body. It takes heaven by storm and gains power over the world. And at the same time Jesuitism means slavery of the will and a denial of man’s creativeness. The real problem of creativeness, so far from being formulated and solved by Christianity, has not even been faced in all its religious implications. It has only been considered as the problem of justifying culture, i.e. on a secondary plane, and not as the question of the relation between God and man. The result is rebellion and rejection of the dominant theological theories.

Human nature may contract or expand. Or, rather, human nature is rooted in infinity and has access to boundless energy. But man’s consciousness may be narrowed down and repressed. Just as the atom contains enormous and terrible force which can only be released by splitting the atom (the secret of it has not yet been discovered), so the human monad contains enormous and terrible force which can be released by melting down consciousness and removing its limits. In so far as human nature is narrowed down by consciousness it becomes shallow and unreceptive. It feels cut off from the sources of creative energy. What makes man interesting and significant is that his mind has so to speak an opening into infinity. But average normal consciousness tries to close this opening, and then man finds it difficult to manifest all his gifts and resources of creative energy. The principle of laisser faire, so false in economics, contains a certain amount of truth in regard to moral and spiritual life. Man must be given a chance to manifest his gifts and creative energy, he must not be overwhelmed with external commands and have his life encumbered with an endless number of norms and prohibitions.

It is a mistake to think that a cult of creativeness means a cult of the future and of the new. True creativeness is concerned neither with the old nor with the new but with the eternal. A creative act directed upon the eternal may, however, have as its product and result something new, i.e. something projected in time. Newness in time is merely the projection or symbolization of the creative process which takes place in the depths of eternity.7 Creativeness may give one bliss and happiness, but that is merely a consequence of it. Bliss and happiness are never the aim of creativeness, which brings with it its own pain and suffering. The human spirit moves in two directions — towards struggle and towards contemplation. Creativeness takes place both in struggle and in contemplation. There is a restless element in it, but contemplation is the moment of rest. It is impossible to separate and to oppose the two elements. Man is called to struggle and to manifest his creative power, to win a regal place in nature and in cosmos. And he is also called to the mystic contemplation of God and the spiritual worlds. By comparison with active struggle contemplation seems to us passive and inactive. But contemplation of God is creative activity. God cannot be won through active struggle similar to the struggle we wage with cosmic elements. He can only be contemplated through creatively directing our spirit upwards. The contemplation of God Who is love is man’s creative answer to God’s call. Contemplation can only be interpreted as love, as the ecstasy of love — and love always is creative. This contemplation, this ecstasy of love, is possible not only in relation to God and the higher world but also in relation to nature and to other people. I contemplate in love the human faces I love and the face of nature, its beauty. There is something morally repulsive about modern activistic theories which deny contemplation and recognize nothing but struggle. For them not a single moment has value in itself, but is only a means for what follows. The ethics of creativeness is an ethics of struggle and contemplation, of love both in the struggle and in the contemplation. By reconciling the opposition between love and contemplation it reconciles the opposition between aristocratic and democratic morality. It is an ethics both of ascent and of descent. The human soul rises upwards, ascends to God, wins for itself the gifts of the Holy Spirit and strives for spiritual aristocratism. But it also descends into the sinful world, shares the fate of the world and of other men, strives to help its brothers and gives them the spiritual energy acquired in the upward movement of the soul. One is inseparable from the other. Proudly to forsake the world and men for the lofty heights of the spirit and refuse to share one’s spiritual wealth with others is un-Christian, and implies a lack of love, and also a lack of creativeness, for creativeness is generous and ready to give. This was the limitation of pre-Christian spirituality. Plato’s Eros is ascent without descent, i.e. an abstraction. The same is true of the Indian mystics. But it is equally un-Christian and uncreative completely to merge one’s soul in the world and humanity and to renounce spiritual ascent and acquisition of spiritual force. And when the soul takes up a tyrannical attitude towards nature and mankind, when it wants to dominate and not to be a source of sacrificial help and regeneration, it falls prey to one of the darkest instincts of the subconscious and inevitably undermines its own creative powers, for creativeness presupposes sacrifice. Victory over the subconscious instinct of tyranny is one of the most fundamental moral tasks. People ought to be brought up from childhood in a spirit completely opposed to the instincts of tyranny which exhaust and destroy creative energy. Tyranny finds expression in personal relations, in family life, in social and political organizations and in spiritual and religious life.

Three new factors have appeared in the moral life of man and are acquiring an unprecedented significance. Ethics must take account of three new objects of human striving. Man has come to love freedom more than he has ever loved it before, and he demands freedom with extraordinary persistence. He no longer can or wants to accept anything unless he can accept it freely. Man has grown more compassionate than before. He cannot endure the cruelty of the old days, he is pitiful in a new way to every creature — not only to the least of men but also to animals and to everything that lives. A moral consciousness opposed to pity and compassion is no longer tolerable. And, finally, man is more eager than ever before to create. He wants to find a religious justification and meaning for his creativeness. He can no longer endure having his creative instinct repressed either from without or from within. At the same time other instincts are at work in him, instincts of slavery and cruelty, and he shows a lack of creativeness which leads him to thwart it and deny its very existence. And yet the striving for freedom, compassion and creativeness is both new and eternal. Therefore the new ethics is bound to be an ethics of freedom, compassion and creativeness.

See B. Vysheslavtsev’s articles in Put: Suggestion and Religion and The Ethics of Sublimation as the Victory over Moralism (in Russian).

See his Mysterium magnum and De signatura Rerum. A. Koyre emphasizes the part played by imagination in Boehme’s philosophy. See his book, La Philosophie de Jacob Boehme.

Editor’s note: In German, Bildlichkeit, which could open a dialogue with the thought of Ludwig Klages.

Maine de Biran justly connects freedom with inner effort.

Hegel has some striking things to say about this category.

See an interesting book by Fiilop Muller, Macht und Geheimnis der Jesuiten. The author is not a Catholic, but his book is a curious apology for the Jesuits and contains instances of subtle psychological analysis.

See my book, Freedom and the Spirit.

The phrasing and cadence of writing in La Chason des Etoiles is totally different ftom Loup des Abeilles. I struggle to follow. The rhythm is unlike how Loup des Abeilles flow like lyrical. Can you tell me why?